An immigrant detainee is sent over 1,000 miles away from his family and lawyer — and fights to return

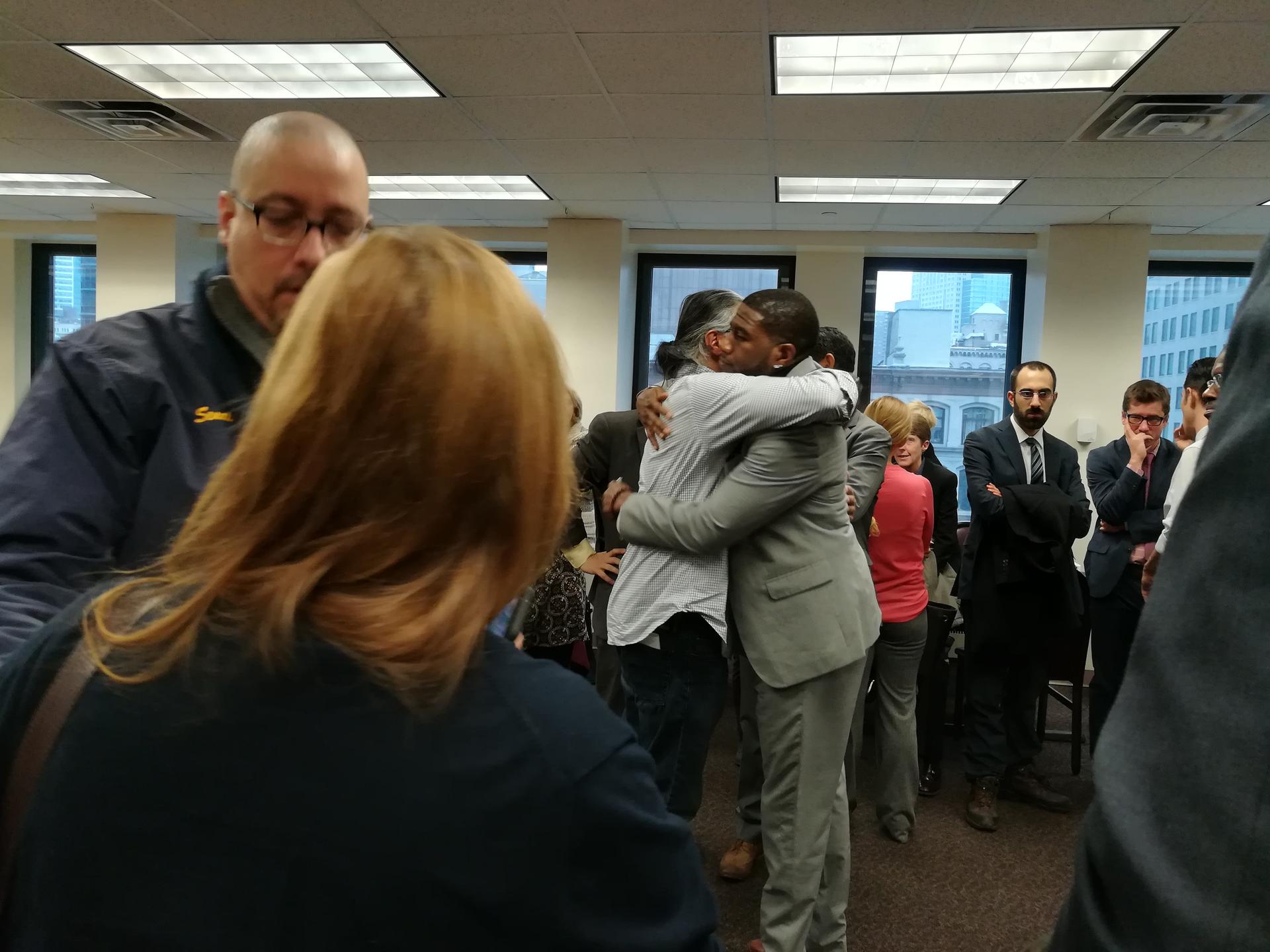

Immigrant advocate Ravi Ragbir hugs New York City Council Member Jumaane D. Williams before he goes to a check-in with federal immigration agents on Jan. 11, 2018. Later that day, the government moved him to a detention facility in Florida.

The last time Amy Gottlieb sat next to her husband was in the ambulance that was taking him to a hospital in lower Manhattan. Immigration agents told her to get out first.

“When I saw them drive away, I actually thought they were driving him to another entrance,” she says. “I was so naive.”

She didn’t know then that the agents were going to get him checked by doctors and then put him on a plane to a detention center over 1,200 miles away.

On Jan. 11, Ravi Ragbir, the executive director of the New Sanctuary Coalition, was taken into custody by immigration agents during a regular check-in in Manhattan. He fainted during the meeting, hence the hospital visit. After he was checked, Immigration and Customs Enforcement booked him in the Krome Detention Center in Miami, Florida.

It was the same facility where the co-founder of the coalition, Jean Montrevil, was taken a week earlier. The government deported Montrevil to Haiti on Jan. 16.

But Ragbir’s fate was different. Federal Judge Katherine B. Forrest had issued a temporary order a few hours after his arrest that he should be held near his family and lawyer while his case is under review. So Ragbir’s lawyer argued that ICE should return him to New York.

ICE took a week to bring him back. He’s now in the Orange County Correctional Facility in Goshen, about 70 miles north of New York City. Lawyers say Ragbir is one of the lucky ones.

“That case is the unicorn case,” says Joshua Bardavid, Montrevil’s lawyer. “It’s the 1 in a million where you’re able to change the location of detention.” Montrevil was held over a thousand miles away from his family and counsel while Bardavid appealed his deportation.

ICE has almost absolute discretionary power to determine where to detain people and where to transfer them. Alina Das, Ragbir’s lawyer, argued to the judge that separating immigrants from their support network causes “irreparable harm.”

Just 14 percent of detained immigrants are able to secure legal counsel, which, in turn, affects the outcomes of their cases. Long-distance transfers make it more difficult for immigrants to find legal representation and also impact how cases are reviewed.

“Federal courts and immigration courts around the country range quite widely in terms of the law they apply and how harsh they are with respect to immigrants,“ says Michael Tan, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union's Immigrants' Rights Project in New York. By transferring people, he says, the government can effectively pick which court they will face and “have the upper hand in people’s deportation cases.”

The challenges are enormous, even when people are detained locally, says Bardavid, whose office is in Manhattan. Sometimes, he spends hours commuting to consult with clients detained in New Jersey. “When they’re detained farther, [it’s] exponentially more difficult.”

A visit to the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, for example, took Bardavid two days. He had to take two flights, rent a car and drive for several hours just to get there.

“Either I do it on a pro bono basis and it’s extremely expensive and time-consuming,” he says, “or I have to ask families who have limited resources to pay for my travel, let alone my time.”

In 2012, the Obama administration responded to growing advocacy against detaining immigrants far from home by adopting new guidelines meant to limit transfers (PDF). That memo, advocates say, helped reduce the number of immigrants being transferred from the New York region while their deportations were being legally challenged.

Ragbir received his final removal order in 2007 after he was convicted of wire fraud. Montrevil’s deportation became final in 1990, after a drug conviction at age 17 for which he served 11 years in prison. Both men were in the US as legal permanent residents, also known as green card holders. Both were in the midst of legally challenging the basis of those orders.

More about Ravi Ragbir: ‘The fear of living as a fugitive is very high’

Dr. Brian Root, an analyst at Human Rights Watch in Los Angeles, studies the way ICE transfers detainees using data collected under the Freedom of Information Act. In 2009 and 2011, his organization published reports on the effects of detainee transfers. Root’s preliminary analysis of data from 2011 through 2014, shows that, despite the Obama memo, ICE continued to transfer detainees away from their home cities.

“I didn’t see a drop,” Root says. “A place like New York” — which has policies to provide legal representation in immigration proceedings — “might have seen a huge drop-off in transfers to places like Florida or Georgia or Alabama. But the overall number has not decreased.”

“If someone is picked up in Georgia, I don’t know if their chances of being transferred across to Louisiana are any less than they were before the memo.”

PRI reached out to ICE, but the agency did not reply to a request for new data since 2014.

Root estimates that approximately 15 percent of all people held in an ICE detention facility from 2011 through 2014, over 5,000 people on average every month, were transferred far from where they were detained while still fighting their deportation orders. Most people were moved from border areas into the interior, and his analysis found no evidence that space constraints at detention facilities were a factor in those decisions.

“There are many transfers a day all over the country and we don’t know exactly why,” Root says in an email.

And those transfers can change everything. For example, the LaSalle Detention Center in Jena, Louisiana, is one of the largest in the country. It holds about 1,000 people at a time, but Root says there are only three immigration attorneys who could possibly represent them within a two-hour drive.

In Louisiana, Florida or most states, detainees also aren’t entitled to certain legal protections they get elsewhere. The US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, in the west of the country, and the 2nd Circuit, around New York, require that immigrants detained for more than six months have a chance to be heard by a judge and released on bond. Those rulings don’t apply at the LaSalle or Krome detention centers.

“It was a big decision,” says Christina Mansfield, co-founder and executive director of San Francisco-based nonprofit Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement. But she says her organization saw a spike in ICE transfers after the 2013 ruling in the 9th Circuit. People who had been detained for a long time in California were being transferred to Alabama. “So none of these people would benefit from the decision, and none of them would be able to get a bond hearing when they had been waiting for one for so long.”

The 2nd Circuit ruling on bonds came in 2015. Das, who is co-director of New York University's Immigrant Rights Clinic, says there are many people with final deportation orders like Ragbir whose ability to challenge their removal is affected by transfers.

“When ICE decides to try and deport those people, being transferred far from their family and friends is precisely what the system is designed to do,” she says. “That’s why Mr. Ragbir works so hard to try and educate people about the immigration system.”

She says it was unusual for ICE to change its position in Ragbir’s case, from allowing him for years to pursue a legal remedy while checking in with the government to suddenly detaining him.

Rev. Juan Carlos Ruiz, one of the leaders of the New Sanctuary Coalition, sees Ragbir’s arrest and Montrevil’s deportation as an attack on their advocacy, an attempt to silence them.

“I thought these tactics were kind of ‘Third World democracies,’” he says. “But I see, more and more, watered-down civil liberties in our democracy. Here in this country.”

In the Jan. 16 hearing of Ragbir’s case, the government’s attorney couldn’t explain why ICE detained Ragbir on Jan. 11 and not, say, on Jan. 19 when his most recent permission to live and work in the US expired. Judge Forrest said, “Seems no one knows that in this room.” She asked immigration authorities to reconsider their position and bring Ragbir back to New York.

Bardavid says he didn’t have the opportunity to make this argument for Montrevil. ICE arrested Montrevil on Jan. 3 in front of his home in Far Rockaway, Queens. Bardavid filed paperwork to challenge his detention in New York, not knowing that ICE had taken him to Krome in Miami.

He says he could barely access his client. Those who tried to visit were told it takes five days to be added to the visitor list.

“Jean couldn’t even call me,” says Bardavid, who has a prepaid account with the private company, GTL, that provides telephone service to the Krome. Montrevil could not access his lawyer’s account. Montrevil was arrested on Jan. 3 and deported to Haiti 13 days later.

ICE did not reply to multiple requests for comment in the last week on the Montrevil or Ragbir cases and about why ICE does these kinds of transfers.

An ICE spokesperson told The Denver Post in September 2017 that the agency does not keep track of transfers between detention centers and that those transfers are related to “operational concerns.” John Sandweg, who was ICE acting director in 2013 and 2014, also told the Post that ICE strives for efficiency.

“Generally, the first priority for ICE is to deport as many people as possible as quickly as possible, and they’re going to use the facility that’s going to help them accomplish that goal,” he said.

Bardavid has filed an appeal with the federal court in Virginia, where Montrevil’s deportation case began. If his argument is successful, Montrevil could be returned to the US.

Ragbir and his legal team used Montrevil’s case as advance warning; they were ready to fight ICE detention and transfer. The next hearing, about whether his arrest on Jan. 11 was lawful to begin with, is scheduled in New York for Jan. 29.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?