As Sumatran rhinos face extinction, scientists come to their rescue

A baby Sumatran rhino. Sumatran rhinos are smaller than their African cousins with long, reddish shaggy hair.

Indonesia’s Sumatran rhino is one of the most critically endangered species in the world, with less than 80 of them left in the wild. Back in the 1980s, scientists hatched a plan to save the Sumatran rhino with a captive breeding program. The program was a flop.

Now, a coalition of conservation organizations, including National Geographic, is hoping to learn from these mistakes and start a new initiative to breed the Sumatran rhino.

Freelance writer Jeremy Hance wrote a series about the plan for the online magazine Mongabay.

“I first met my first Sumatran rhino in 2009,” he says. “I was in Sabah, in Borneo, and I went and met a rhino named Tam. I was told before I met Tam that he was very sweet and kind of like a giant cat, and I thought, ‘That’s ridiculous.’ So, I get there — and he is. He’s rubbing up against the bars next to me. He’s in this beautiful sanctuary in the rainforest. He’s snorting at me, he’s whistling at me. Spending time with this animal face-to-face, I just kind of fell in love and I’ve been following this story obsessively ever since.”

Sumatran rhinos are the oldest rhinos on Earth and they’re “the weirdest,” Hance says. They are the smallest, they have a flank of reddish hair, they live in the rainforest and they love spending time in the mud.

The Sumatran rhino is also related to the extinct Wooly rhino and is the last rhino in their particular genus.

“It’s also the most vocal of rhinos. So, it will sing to you,” Hance says. “Researchers compare its voice and the sounds it makes to whales and dolphins.”

Sumatran rhinos are so endangered because they’ve been hunted for tens of thousands of years by humans and they are still being poached in the wild for their horns.

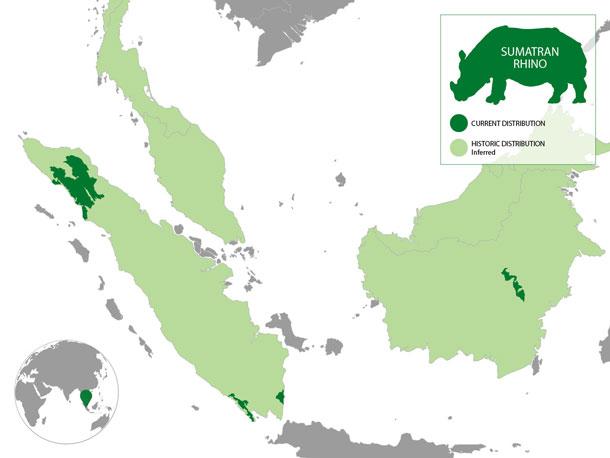

They have also lost much of their habitat to deforestation. But the most critical reason may just be that there are so few left.

“They’re not mating in the wild and they’re not having babies,” Hance explains. “Basically, the population gets so small that, even though there’s some habitat left, there are just not enough of them to replenish the population.”

Making matters worse, Indonesia is an archipelago of islands, so the rhinos that still exist are separated geographically.

Hance’s story for Mongabay focused mainly on the botched effort in the 1980s to save the Sumatran rhino from extinction by trying to breed them in captivity. Having had success with White, Black and Indian rhinos, the scientists believed they could be equally successful with this rhino, so they decided to capture some and place them in various facilities in Malaysia, Indonesia, the US and the UK.

“What happened from that was a total disaster for about two decades, until they finally achieved some success,” Hance says.

A lot of things went wrong. The scientists weren’t feeding them correctly, there were accidents during capture, there was disease.

“Basically, it took scientists, zookeepers and conservationists about 10 to 20 years to figure out how to feed them right, how to care for them and what diseases were cropping up,” says Hance.

Even worse, they could not get the females to become pregnant, Hance says. For the first 17 years, there were no babies. Terry Roth, an employee at the Cincinnati Zoo in Ohio, discovered that female rhinos do not ovulate under certain conditions, apparently. They are what Hance calls “induced ovulators,” and when Roth figured this out, they were able to achieve a successful pregnancy that produced a rhino baby in 2001.

Now, conservationists and biologists have a new plan to save the Sumatran rhino. The Sumatran Rhino Rescue is a consortium of various conservation groups, including National Geographic, Global Wildlife Conservation and the International Rhino Foundation. They plan to once again try to breed the rhinos in captivity.

Right now, only two proven breeders live in captivity and the rhino is still disappearing from the wild, Hance explains.

“So, the idea is, if we can go into the field, capture a few healthy females and maybe a couple of more males, we can supplement the captive breeding program and make that a success, and then ensure that the species doesn’t go extinct,” he says.

Hance says he is cautiously optimistic about the new effort because he says “we’ve done this before.”

“The European bison went extinct in the wild — down to 12 animals — and they brought it back and now there are 4,000 in Europe,” he notes. “So, we can do this. This is not impossible. We just need the money, the support and collaboration. Things are going to go wrong. It’s not going to go perfectly. I’m sure there will still be tragedies. But, having met some of these baby animals when I visited the sanctuary in Indonesia — and met the people who take care of them every day — that’s what makes me optimistic.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?