Kenny Fox at his cattle ranch in Belvidere, South Dakota. Fox, who is a third-generation South Dakota rancher, would like his sons to be able to continue in his footsteps, but worries that the economics are making it too difficult.

This is a story about two ranchers in western South Dakota — Kenny Fox and Eric Jennings.

The two men have both been busy vaccinating and branding their calves, and preparing to get hay ready for winter. Fox is in his 60s; Jennings is in his 50s. Their lives, jobs and outlooks have a lot of overlap. Where the two men differ sharply, however, is on trade.

“We have people who have lost jobs because of NAFTA,” says Fox.

On the flip side, Jennings says, “We’re very happy with NAFTA. It has opened up our borders tremendously.”

The North American Free Trade Agreement is at a crossroads — renegotiations for the 24-year-old trade deal started last August. The three parties — the US, Canada and Mexico — have made some progress, but don’t appear close to an agreement, with President Donald Trump continually threatening to walk away from the trade pact if he can’t get a better deal.

NAFTA is generally seen as positive for most segments of US agriculture. For beef, the pact got rid of tariffs and quotas between the three nations. Since NAFTA came into effect in 1994, US beef exports to Mexico have increased by more than 450 percent, while exports to Canada have more than doubled.

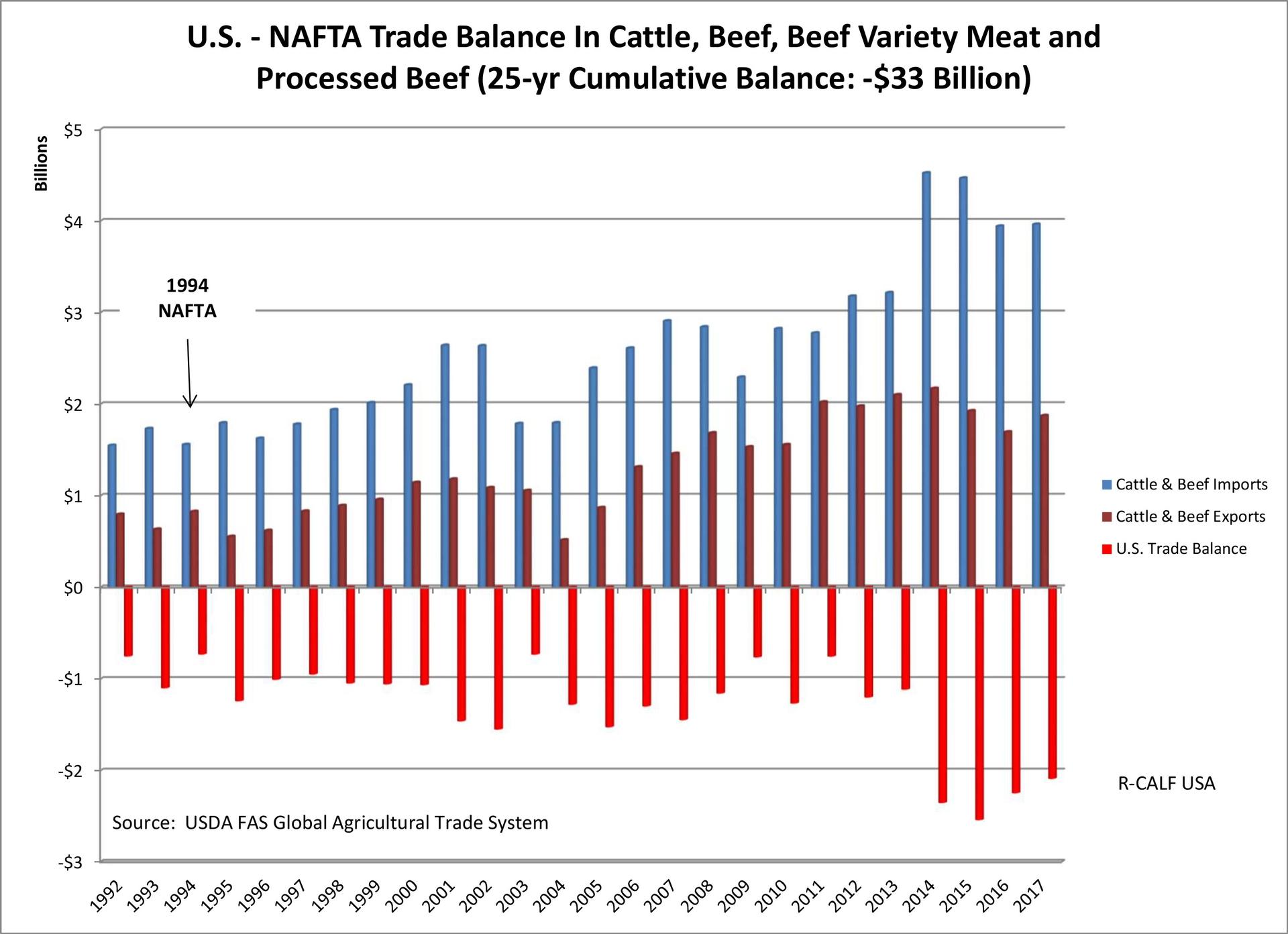

But sales are going in every direction. Beef, and live cattle, imports to the US from Canada and Mexico have also risen sharply in the time of NAFTA. During that time, the US has accumulated a $32 billion trade deficit for beef products. And that’s why Fox, the farmer opposed to NAFTA, doesn’t like the trade deal.

“I don’t think we need as many cattle coming into this country as there is,” says Fox. “That is causing people to go out of business. It is causing young people not to go in because it costs so much money to get started.”

Economists say trade deficits don’t really matter — they’re simply a reflection of products going from where they’re most efficiently produced to where there’s demand. And since NAFTA came into effect, beef production is up in all three nations. Still, for established cattle men like Fox, more competition can often mean more work for less money.

“We repair what we got instead of buying new. We don’t build new fences. We just kind of limp along and hope for the best,” says Fox.

These days, however, he’s got more hope that things will change.

“President Trump is the only ally that we really have [in Washington],” says Fox. “And I feel that he has done more in the short time he’s been there than any president that I know of in my lifetime.”

Fox is a member of R-Calf USA, a nationwide organization of cattle ranchers. Bill Bullard, the organization’s CEO, says since NAFTA came into effect, imports of Mexican and Canadian products have taken a toll.

“Since the 1994 implementation of NAFTA, we have lost 20 percent of all of our beef cattle operations in the United States,” says Bullard.

There’ve also been other factors at play during that time: droughts, technological advances and consolidation of farms.

Bullard says they’re not opposed to competition, just unfair competition. He says stricter American regulations make it more expensive to produce beef in the US than in Canada or Mexico. And his organization argues that Canadian and Mexican cattle ranchers get more help from their respective governments.

Bullard says NAFTA needs some key revisions to protect American cattle ranchers.

“If Mexico can produce cattle far cheaper than the United States, then we should add tariffs to that product coming into this country so that our beef produced under the US production regime can compete with the Mexican cattle,” says Bullard.

His organization also wants other issues addressed by American trade negotiators, like restoring country of origin labeling for beef and implementing stricter food safety standards. And Bullard says if NAFTA can’t be fixed: “We should rip it up.”

Then there is the other US perspective on NAFTA coming from The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. The headline of their one-page summary reads: “US Beef Under NAFTA: An Export Success Story.”

As a cattle rancher, you kind of have to choose sides, like going with the Mets or the Yankees; it’s hard to support both. Eric Jennings, the rancher who supports NAFTA, chose the Cattlemen’s Beef Association, but he’s a fish out of water in South Dakota.

“I’m surrounded with R-CALF members,” says Jennings. “I know their position, and they know my position. We all get along, we all work together. We respectfully disagree with each other. We know that we’re not going to change each other’s minds.”

The import/export equation of beef is complicated — it’s essentially the trade of animal parts — and Jennings says since NAFTA came into effect, his cattle have actually become more valuable.

“We sell a lot of round cuts — that’s a rump cut off of a steer — that go down to Mexico. They also take a lot of tongue. We don’t eat a lot of tongue in America,” says Jennings.

He says exporting tongues and livers, and not just to Mexico and Canada, gets him an extra $150 to $180 per head of cattle. And he says a lot of Mexican and Canadian beef imports get mixed in with American hamburger meat, which frees him up to export higher-value cuts, like flat iron steaks, to other nations. Accepting imports in return, that’s just part of free trade.

Jennings doesn’t want to go back to the way things were before NAFTA.

“It takes a long time to build relationships for trade and it doesn’t take very long to get rid of them, to destroy that relationship,” says Jennings. “It’s a competitive world and there’s other countries looking to move in on the markets that America has right now.”

Trump has recently said that if the US can’t get a better NAFTA, he’ll pursue separate trade agreements with both Canada and Mexico. The two nations have both rejected that idea.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?