What reporters couldn’t see when they toured a Texas shelter for child migrants

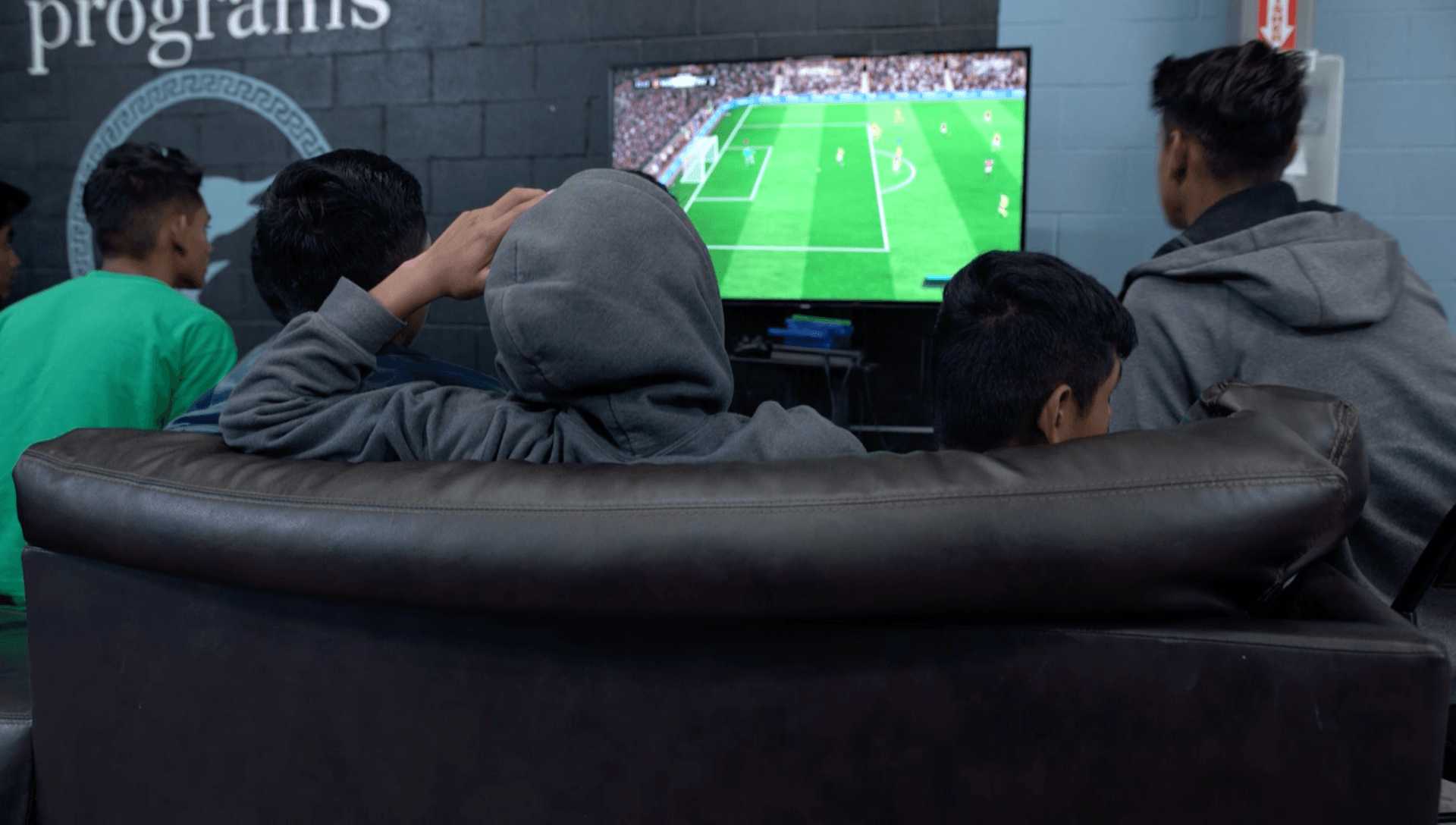

Teenage boys play video games at Casa Padre, a facility for migrant children in Brownsville, Texas.

Life for children inside a privately run facility for migrant children at the Southern border is a cross between living in a detention center and temporary shelter.

That’s according to people who got a brief glimpse inside. This week, a small group of reporters toured Casa Padre, a converted former Walmart in Brownsville, Texas, that houses nearly 1,500 boys ranging in age from 10 to 17 who were caught crossing the border between checkpoints. Most come from Central America.

Casa Padre is one of approximately 100 facilities for recently arrived migrant children throughout the country, as well as the largest. Though most of the children there are unaccompanied minors, meaning they crossed the border on their own, a growing segment of child migrants in government care is those who were separated from their parents under Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ new “zero-tolerance” policy.

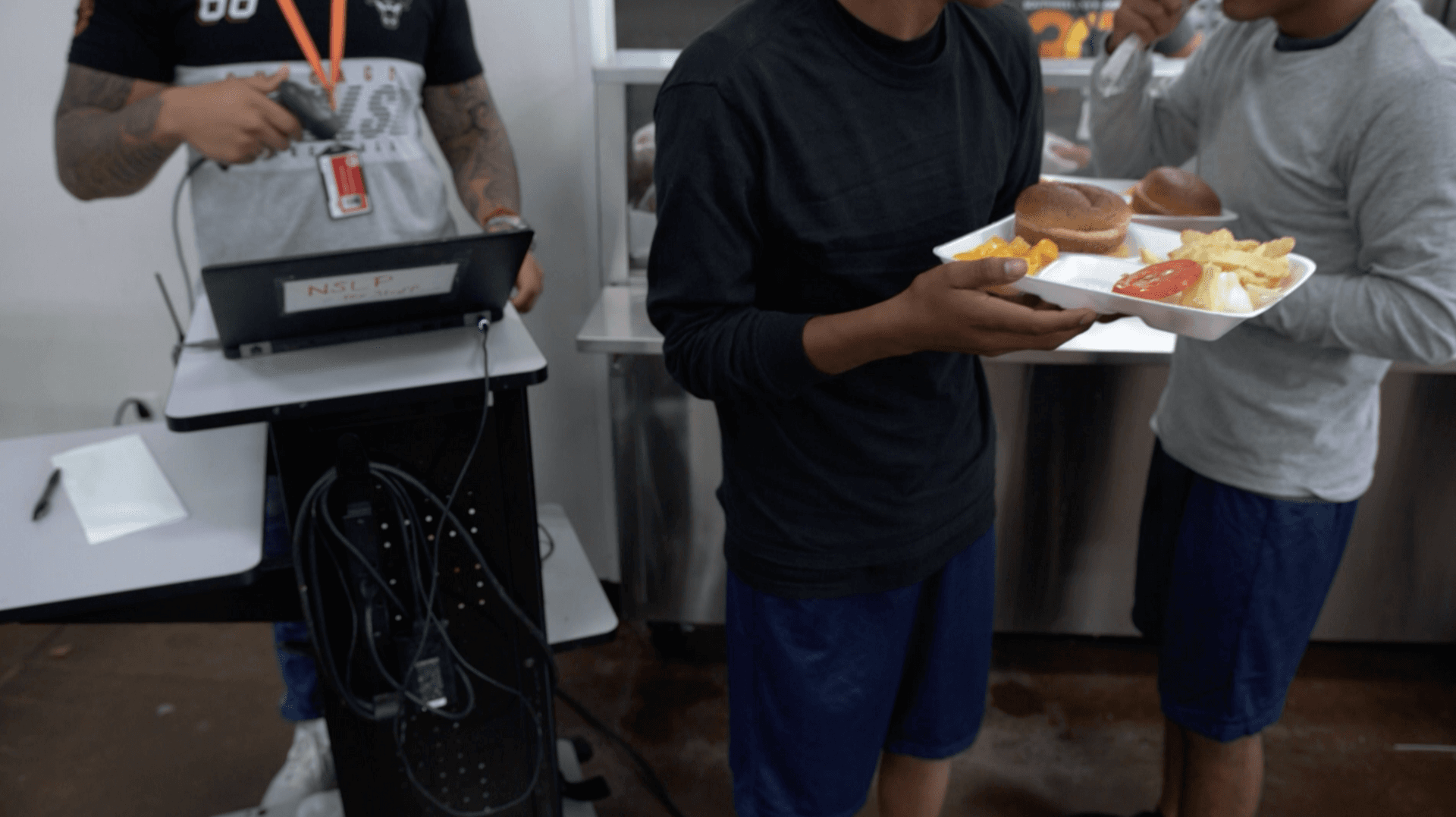

Reporters who visited told PRI they saw good conditions overall. Children are not kept in cages or cells. They’re free to move around, but they’re not allowed to leave the center. They get two hours per day outside. But because the center is overcrowded, five beds are packed into rooms built for four.

“I think the reason that we were having this walk-through was to dispel some of the rumors that kids were being held in cages,” says Aaron Nelson, the Rio Grande Valley bureau chief for The San Antonio Express-News. Nelson went on the government tour with a group of other reporters. “It looked something like how I might describe a charter school…You had an area when you first walked in, there was a cafeteria, pretty nice kitchen. There were brightly colored murals painted all over the walls in other areas. There was a barbershop. There were indoor and outdoor basketball courts, pool tables, kids playing video games on big screen TVs. There was a movie theater playing ‘Moana’ in Spanish. There were classrooms. There was a medical area.”

Casa Padre got national attention last week when US Senator Jeff Merkley attempted to tour it, but was turned away by staff.

“I think that there was a sense among the other journalists who were on this tour that this was kind of, in the words of one reporter, the Rolls Royce, perhaps, of the shelter network,” Nelson says. “But I think it’s also important to note, we don’t have the opportunity to talk to the kids, so it’s difficult to know.”

Indeed, the hardships for children — even in a relatively organized facility like Casa Padre — go far beyond what meets the eye, says Jennifer Podkul, director of policy for Kids in Need of Defense. The organization represents detained children in two Seattle facilities similar to Casa Padre. It also represents children who have been released to the care of “sponsors,” typically a relative or family friend, after weeks or months in detention.

She says this is essentially a manufactured crisis, one Trump and Sessions have worsened through their policy to prosecute everyone who crosses the border between checkpoints. That policy puts adult migrants into prisons and their children into the care of the US government.

“What’s happening now is that kids that would otherwise, or normally would have been deemed accompanied, are now suddenly unaccompanied because we, the United States, are saying we want to criminally prosecute their parents,” Podkul says. “The parents are being criminally prosecuted, but the kids are not.”

She says Kids in Need of Defense is helping 40 children whose parents do not know where they are or have been deported without them.

“They are not reunifying these families — not even at the point of the parents’ deportation,” Podkul says.“They are making no efforts to help people stay in touch or even know where their family member is.”

The Department of Health and Human Services did not return requests today for information about the shelters or how they operate. They said they are processing the request.

Juan Sanchez, the president and chief executive of Southwest Key Programs, the federally contracted nonprofit that operates Case Padre and 26 other migrant centers in Texas, Arizona and California, paints a different picture of his organization’s facilities.

“We take great care of kids,” he told the Houston Chronicle. “Our goal is to reunify these children with their families.”

But Podkul says reunions were far more frequent — and easier — prior to the zero-tolerance policy, which was tested last year and fully implemented last month. That’s because the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, is accustomed to dealing with unaccompanied minors, who are children under 18 who arrived in the US alone.

Now, that office is seeing increasing numbers of children who are arriving in their care with no information about relatives or their potential asylum claims because they were separated. That information remains with their parents.

“ORR is really being put in a difficult position because they’re getting hundreds of children they wouldn’t otherwise get, and ORR still has a mandate to reunify the kid with their parents,” Podkul says. “But ICE and US marshals that have the parents in custody are not telling them where the parents are.”

The zero-tolerance policy went into effect last month. On May 7, a week after a “caravan” of about 200 migrants from Central America arrived at the border in Tijuana, Mexico, Sessions held a news conference in front of the border fence near San Diego.

“I have put in place a zero-tolerance policy for illegal entry on our southwest border. If you cross this border unlawfully, then we will prosecute you. It’s that simple. If you smuggle illegal aliens across our border, then we will prosecute you. If you are smuggling a child, then we will prosecute you and that child will be separated from you as required by law,” he said.

More: This is what the ‘zero-tolerance’ policy on the border means for people fleeing violence

The Immigration and Naturalization Act allows migrants to ask for asylum, whether they entered through a port of entry or not.

A Department of Homeland Security (DHS) spokesperson told PRI by email that the new orders mean anyone crossing the border between checkpoints will be prosecuted, including those fleeing violence or who ultimately seek asylum.

Some 11,200 children are in federal custody right now, according to government officials, a growing segment of whom have been separated from their parents. Though Casa Padre focuses on teenage boys, other facilities house girls and younger children.

Podkul says unaccompanied minors have difficulties navigating the US immigration system. Children separated from their parents have an even tougher time.

“Kids who traveled to the US by themselves — they’ll talk about their experiences, their hopes, their case. But these separated kids are talking about how they’re worried about their parents,” Podkul says. “My colleagues are spending so much time trying to find family members, because it’s the family member who has all the information on the threat they faced. It’s the adult who usually carries the paperwork, like a birth certificate or a police report they filed in their home country. It’s really hard for us to work on these cases.”

Sanchez, for his part, declined reporters’ request for comment on the zero-tolerance policy. He also said the facility is not a detention center.

“What we are about, and we do it very well, is we take care of kids,” Sanchez said.

Southwest Key, which employs more than 1,200 people at Casa Padre, has a ratio of one case manager for every eight children, according to the Houston Chronicle’s report on the tour. It has a 48-person medical staff with three on-call physicians.

Still, the Associated Press has reported that state regulators found approximately 150 health violations at Southwest Key’s 16 shelters across Texas. Among the 13 violations at Casa Padre were instances of inadequate supervision and lack of timely medical care, including a two-week delay in treatment for a minor who tested positive for a sexually transmitted disease.

Anticipating many more migrant arrivals over the summer, Trump administration officials said this week they are considering erecting tent cities on one or more military bases to house unaccompanied or separated children.

With additional reporting by Angilee Shah