Another time in history that the US created travel bans — against Italians

Little Italy on Mulberry Street in New York City in 1900. In the next 20 years, the US passed strict laws to restrict Italian immigration.

There was a time in US history when the government thought that a country was “not sending its best.” A time when the government thought that immigrants’ home countries could do more to help them screen who gets to come to the US.

It was Italy in the 1920s.

The way the Sudanese and US governments negotiated to keep Sudan off of the Trump administration’s third travel ban is not a new diplomatic maneuver. A century ago, Italy too tried to negotiate its way out of restrictive immigration policies.

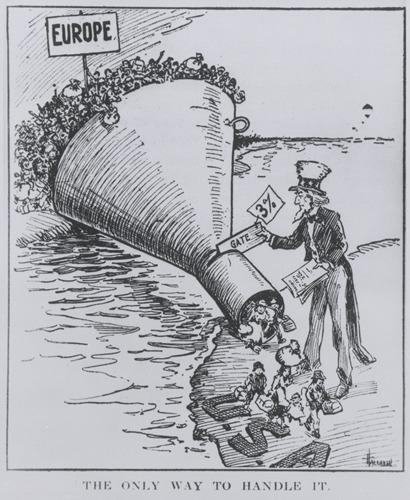

Like today, Americans at the end of the 19th century had fierce debates about which immigrants to admit to the US. In the midst of the largest global migration in history, many Americans remained divided over the need for immigrant labor to propel the country’s meteoric economic rise and the desire to protect the US from immigrants from “inferior” countries — at that time, China, Italy or Russia.

More: In 1891, 11 Italians were lynched in New Orleans.

As one newspaper noted in the 1890s: “The floodgates are open. The bars are down. The sally-ports are unguarded. The dam is washed away. The sewer is unchoked. Europe is vomiting! In other words, the scum of immigration is viscerating [sic] upon our shores.”

Under pressure from a small but very organized lobby, the US government responded by passing increasingly sweeping immigration laws that spelled out which immigrants were admissible and which were excluded. They created barriers for those considered to be a threat — physically, culturally or politically.

Despite the draconian legislation then, like now, the US could not hope to monitor who entered the country without the collaboration of other countries. It had influence but could not enforce its immigration laws by itself. So, the government established mechanisms of “remote control,” and demanded that other countries cooperate in a visa-vetting regime.

It’s not unlike what the Trump administration is demanding today.

In the early 1900s, Chinese immigrants were already severely restricted. Established political leaders of northern and western European descent turned their attention to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Italians, often labeled “the Chinese of Europe,” were the largest immigrant group at the beginning of the 20th century so they became one of the primary targets for restrictive immigration laws. (The other targeted group was Eastern European Jews.)

By 1914, many Americans agreed with Bishop Charles Henry Brent of the Protestant Episcopal Church that “the United States is in far greater danger from the quality of immigration that comes from Southern Europe than from any peril that could come by Japanese ownership of lands in California, or from Asiatic immigration.”

By 1917, US immigration laws categorized potential immigrants by socioeconomic status, literacy, criminality, political beliefs, diplomatic standing, physical and mental health and sexuality. And increasingly, the burden of selecting the “right” immigrants to come to the US rested with the governments of the immigrants’ countries of origin.

Italy, as well as Poland and the former Yugoslavia, had little choice but to comply with US requests to change how they treated their own citizens. The US demanded a uniform passport system, that Italy allow American doctors on Italian soil for medical inspections, and that Italian officials collaborate with US embassies and consulates to issue new types of documents to Italians who wanted US visas.

With remote control in place, many aspiring Italian immigrants never left for the US in the first place.

The Italian government saw these demands as an infringement on its sovereignty, but it collaborated anyway because it hoped that the US would not pass more stringent immigration laws. They had a stagnant economy, while work was plentiful in the Americas, and the remittances Italians sent home were significant. Ironically, the more Italy tried to make sure that only “desirable” immigrants went to the US and the more they tried to protect Italians already in the US, the more American legislators called for restriction.

Many Americans and restrictionist legislators believed that the Italian government could do more to weed out “undesirable Italians” but didn’t because it wanted to get rid of them. At one point in the early 1920s, the Italian government was prepared to put a temporary moratorium on Italian emigration to the US while they established stricter immigration controls, if Congress agreed not to pass legislation that would further limit how many Italians the US would admit. The Italian government’s efforts were to no avail, however.

The result was the 1924 Immigration Act, one of the most restrictive immigration laws in US history. The act created a national origins quota system that allowed only a small number of people to immigrate from eastern and southern Europe, banned most immigration from Asia, and created new restrictions for immigrants from the Americas, particularly Mexicans. The majority of the quota slots went to immigrants from northern and western Europe, people with white Anglo-Saxon heritage.

By the 1920s, however, very few immigrants from Britain, Germany or Ireland came to the US even though they had more opportunity to do so.

The 1924 Immigration Act did lead to a reduction of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, but, historically speaking, these arbitrary and discriminatory laws set in motion a series of unintended consequences. It forced the US to create a bigger and more expensive immigration infrastructure at home and abroad to enforce the new rules. The buildup of this system in Italy created a new and more insidious problem to solve: many aspiring Italian immigrants lacking the money to apply for a visa or a passport snuck out of the country, often through France, and then tried to reach the US from there. These migrants then became “illegal” both in the US and Italy.

The strict immigration system set up in the 1920s alienated many Allied countries in Asia during World War II and undermined US aspirations of global leadership during the Cold War. It also led to one of the US’s worst moral failures of the 20th century: It turned away Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Europe because they came from countries with small allotted quotas. Quotas for countries with many Jewish refugees went unfilled through the 1930s and 1940s, including a very generous quota for Germany, because State Department officials systematically denied visas or rejected refugees.

Fast forward to today, and the lesson might be one of caution. Countries that collaborate with the Trump administration to control migration cannot guarantee that their citizens will not later become a target of its restrictive policies.

Maddalena Marinari is assistant professor of history at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota. She teaches a broad range of courses on 20th century US history and writes about immigration, immigration restriction and policy history. She was among a group of historians who helped Global Nation annotate the first version of Trump’s travel ban.

More: The US has come a long way since its first, highly restrictive naturalization law