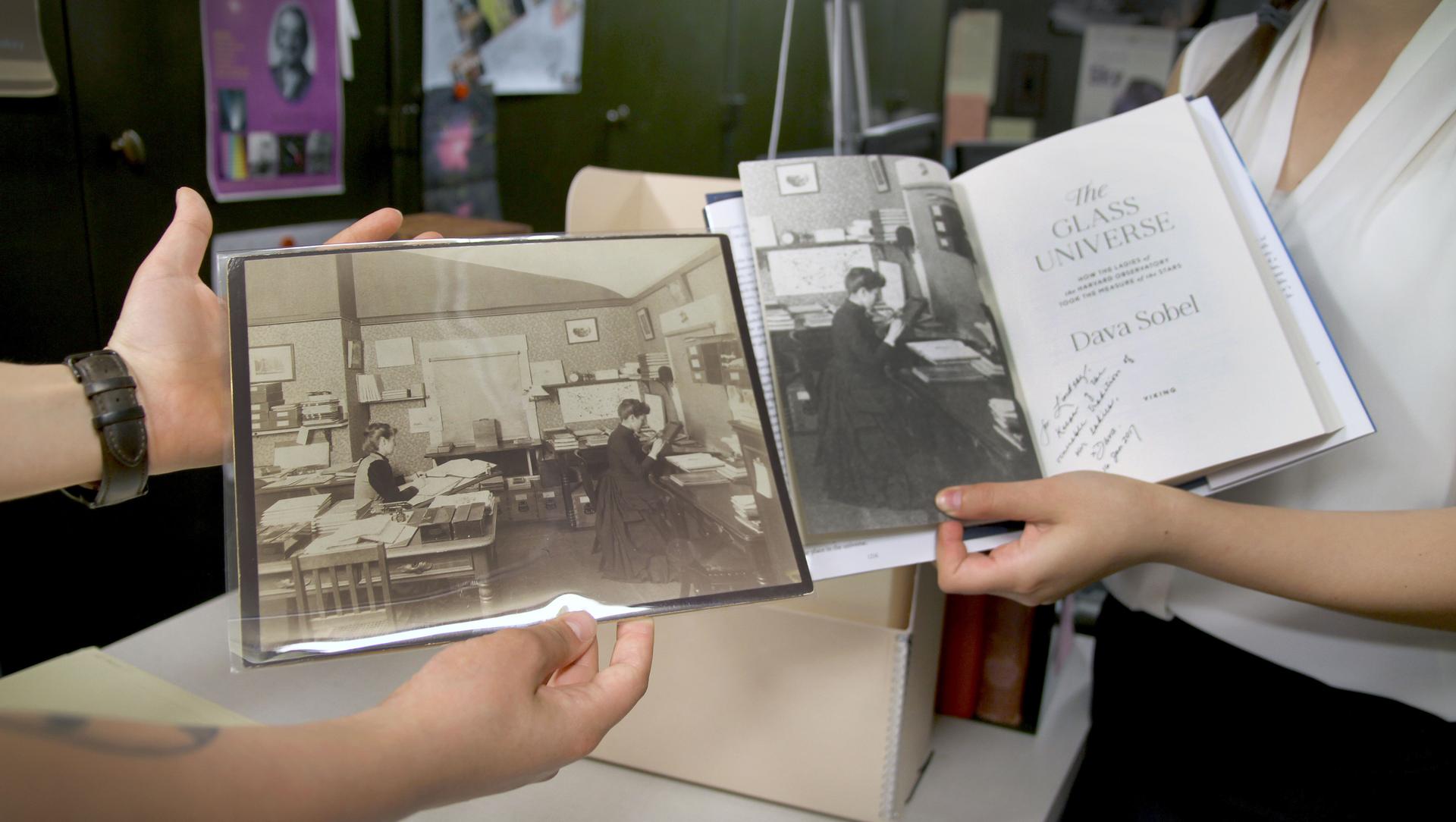

Curator Lindsay Smith Zrull places a glass plate photograph of a section of the sky onto a lightbox. Smith Zrull recently discovered boxes of notebooks belonging to early women astronomers who studied the glass plates as early as 1885.

In a cramped Harvard University sub-basement, a team of women is working to document the rich history of their predecessors.

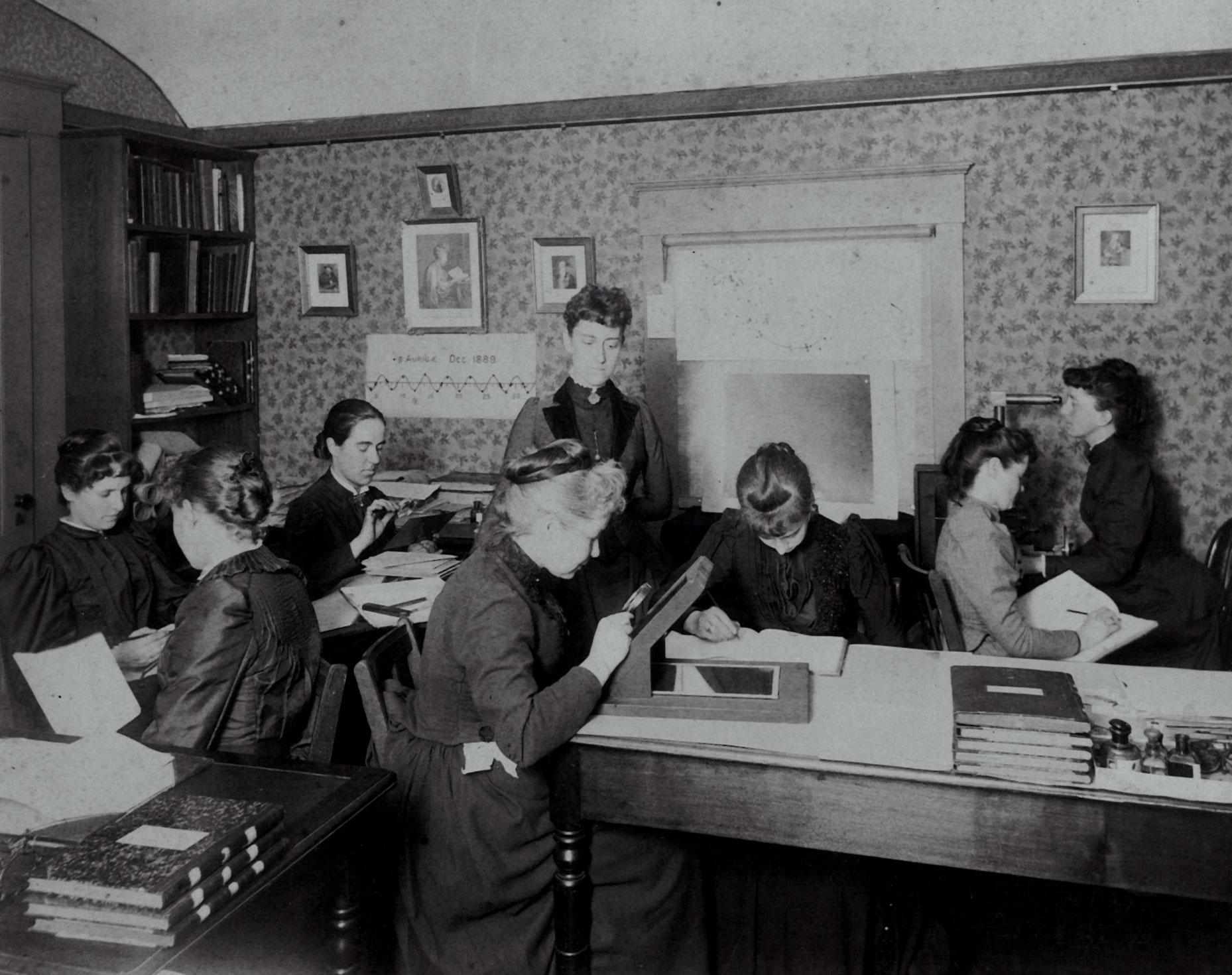

More than 40 years before women gained the right to vote, women labored in the Harvard College Observatory as “computers” — astronomy’s version of NASA’s “Hidden Figures” mathematicians.

Between 1885 and 1927, the observatory employed about 80 women who studied glass plate photographs of the stars, many of whom made major discoveries. They found galaxies and nebulas and created methods to measure distance in space. In the late 1800s, they were famous: newspapers wrote about them and they published scientific papers under their own names, only to be virtually forgotten during the next century. But a recent discovery of thousands of pages of their calculations by a modern group of women working in the very same space has spurred new interest in their legacy.

Surrounded by steel cabinets stuffed with hundreds of thousands of plate glass photographs of the sky, curator Lindsay Smith Zrull shows off the best of the collection.

“I have initials but I have not yet identified whose initials these are,” Smith Zrull says, pointing at a paper-sized glass plate crowded with notes taken in four different colors. “One of these days, I’m going to figure out who M.E.M. is.”

Each glass plate is stored in a paper jacket and initialed to show who worked on it, but for decades no one kept track of the women’s full names. So Smith Zrull started a spreadsheet about 18 months ago and adds initials when she discovers new ones and then tries to locate the full names in Harvard’s historical records.

“I’m slowly starting to piece together who was who, who was here when, what they were studying,” she says. Smith Zrull has about 130 female names and about 40 are still unidentified.

Not all are computers. Her list has grown to include assistants and, in some cases, astronomers’ wives who helped with their husbands’ work.

“We know there were at least 80 women who worked in this space on these glass plate photographs, which is a pretty amazing number considering women were still trying to get social approval to go to college, let alone work in the sciences,” Smith Zrull said.

In the Plate Stacks at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics — the modern version of what was once called the Harvard College Observatory — Smith Zrull oversees a digitization project to make the glass plates available to the world. Since 2005, a custom-built scanner has been making its way through the collection of more than half a million plates from 1885 to 1993. The team scans 400 plates per day — they’re at about the halfway point now — and Smith Zrull estimates about three years of scanning remains.

‘People forgot they were there’

Last fall Smith Zrull turned her attention to about 30 notebooks in the plate stacks belonging to the women computers.

“I started to realize a lot of these books were missing,” she says. “I started doing a little bit of digging and eventually came across some proof that we might have boxes in storage off-site, which is very common for libraries around Harvard.”

Smith Zrull found 118 boxes, each containing between 20 and 30 books. Inside were more notebooks from the women computers and notebooks from astronomers who predated photography and made hand-drawn sketches of planets and the moon.

“People didn’t know they existed when they were in storage,” Smith Zrull says. “As different curators came and went here, I suppose people forgot they were there. Now that we know they exist, we can make them accessible to the public, they can be cataloged in a library so people can come across them.”

The books had moved from one library to the plate stacks to another library to a book depository, essentially lost to history until Smith Zrull began looking for more information on the women computers.

To resurrect their legacy, she enlisted the help of librarians from the Wolbach Library in the Center for Astrophysics. The librarians prepared to manually go through the boxes and begin the labor-intensive process of cataloging them. Project PHAEDRA (an acronym for Preserving Harvard’s Early Data and Research in Astronomy) was born.

‘OK, we’ve hit pay dirt’

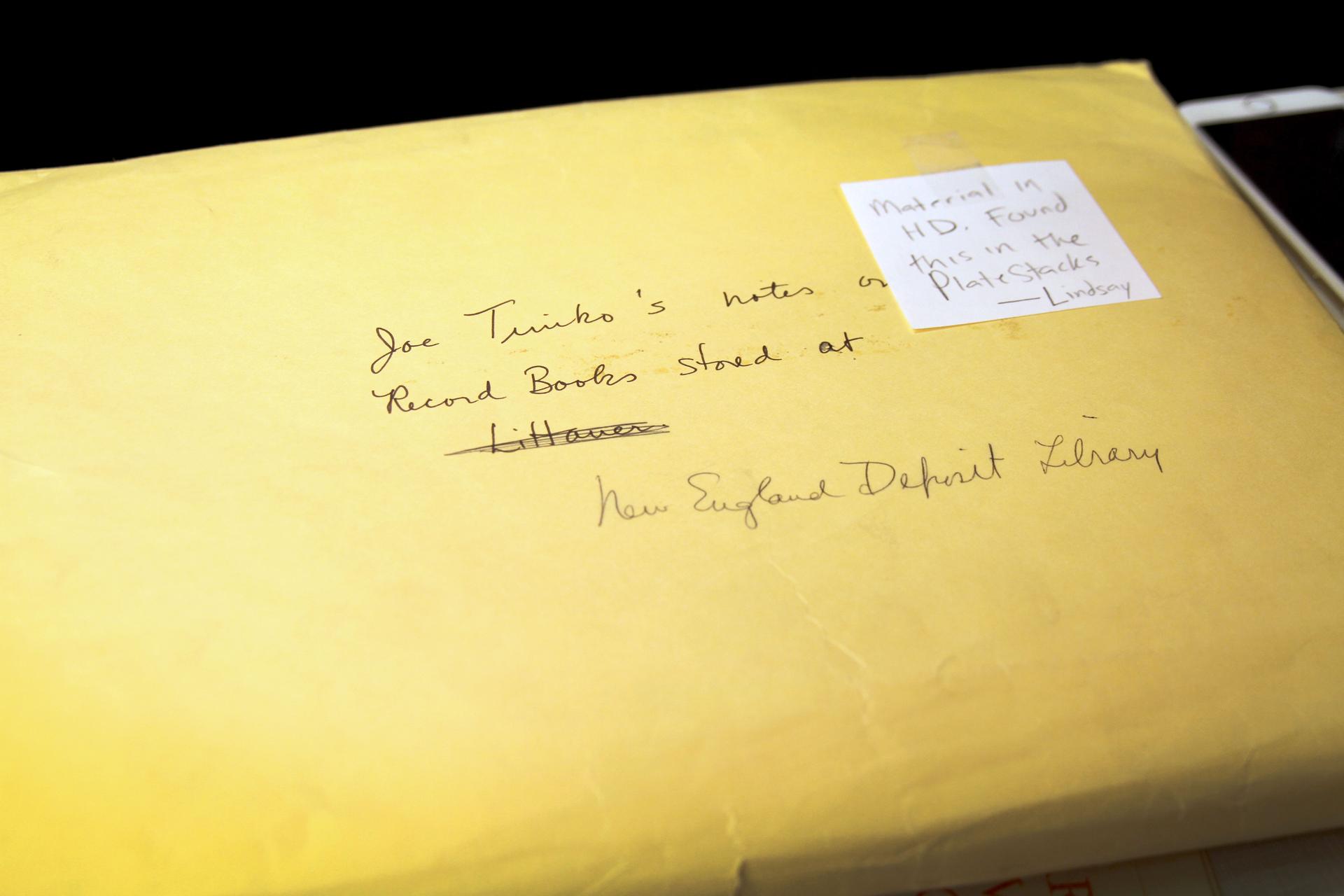

Then Smith Zrull made another discovery in the plate stacks: a handwritten catalog of the books from 1973.

“At some point in 1973, someone who we assume is named ‘Joe Timko’ went through all of these boxes at an item level and recorded as much information as he could find,” says head librarian Daina Bouquin. “We have no sense of why this was done or what became of the person who did this, but we thought, ‘OK, we’ve hit pay dirt.’ ”

Then someone found a typewritten version of the 1973 catalog, adorned with a Post-it saying “Finally done! Rachel.” On the very last page was a handwritten path to a computer file, a spreadsheet on a Harvard server that hadn’t been accessed since 2001.

The discovery sped up the digitization project by months, if not years.

“We went from having absolutely no metadata, like 30 characters on each box, to having item-level, machine-readable, type-written metadata that we could then edit and clean up and turn into real records,” explains Bouquin. “Thank you Joe Timko and possibly Rachel, wherever they may be.”

The library has completed transcription of about 200 volumes. Right now, notebooks from two women are listed on the Smithsonian Transcription Center website. There are many more to come — nearly 2,300 out of a total 2,500 books — but the work has begun. Bouquin hopes the public will help transcribe the books, but anticipates it will still be years before everything is readable.

“You’ll be able to do a full-text search of this research,” Bouquin says. “If you search for Williamina Fleming, you’re not going to just find a mention of her in a publication where she wasn’t the author of her work. You’re going to find her work.”

‘She’s the one who really found it’

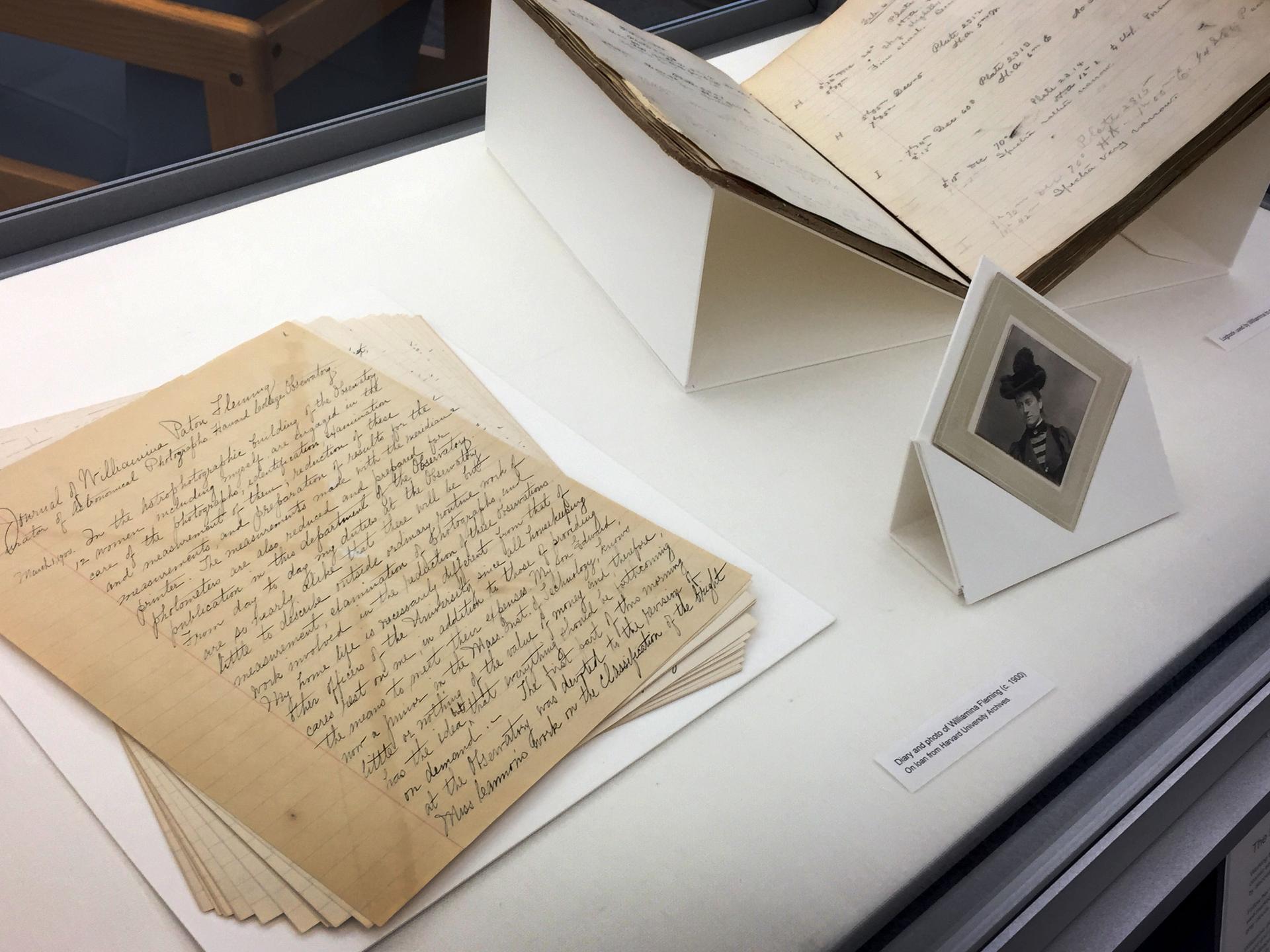

Fleming is the first famous woman computer. Fleming emigrated to the United States from Scotland in the late 1870s. While pregnant, she was abandoned by her husband and found work as a maid in the home of Edward Pickering, the observatory director. In 1881, Pickering hired Fleming to work in the observatory. She would go on to discover the Horsehead Nebula, develop a system for classifying stars based on hydrogen observed in their spectra and lead more female computers.

Wolbach Library unveiled a new display case in early July showcasing Fleming’s work. The case includes pages from her diary as well as her work on the plates showing the nebula and the log book containing that discovery.

“When the [Horsehead Nebula] was discovered, it was just a little ‘area of nebulosity in a semi-circular indentation,’” says librarian Maria McEachern, who has helped the team sort through the notebooks to find the more interesting pieces. “That’s how it was described at the time. It wasn’t until years later that it became known as the Horsehead Nebula and one of the male scientists at another institution who named it was the one who got credit for it. It wasn’t even until recently that people have been doing more scholarship and finding out that, yes, she’s the one who really found it.”

But Fleming was just the first of many to become famous.

Pickering hired Henrietta Swan Leavitt in 1895. She was tasked with measuring and cataloguing the brightness of the stars. Her major discovery: a way to allow astronomers to measure distance in space, now known as “Leavitt’s Law,” an attempt to give her credit for her work.

Annie Jump Cannon joined the observatory in 1896 and worked there until 1940. Cannon created the Harvard Classification System for classifying stars, which is the basis of the system still in use today.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin came to the Observatory in 1923 and earned a doctorate from Radcliffe in 1925, but she struggled to get recognition from Harvard. For years she had no official position, serving as a technical assistant to then-director Harlow Shapley from 1927 to 1938. It wasn’t until the mid-1950s that she became a full professor and later, the first woman to head a department at Harvard.

Payne-Gaposchkin’s notebooks will be the next set scanned and submitted for transcription. (Leavitt and Cannon’s notebooks are in the process of being transcribed.)

‘They’ve always been there’

“I like to think resilience goes a long way, but I think some of these women go a little above and beyond what we think of when we think of overcoming things,” Bouquin says.

Both Bouquin and Smith Zrull said they want to give young girls more role models like the Harvard computers — role models who weren’t well-known when they were young.

“Yes, look at Sally Ride, look at modern women who people associate with the space-based sciences, but go back further,” Bouquin says. “They’ve always been there. As long as they could be, they were there.”

Smith Zrull — who hated history as a teen — said she struggled to find women who encouraged her.

“It really took me a long time to start to find women who I felt were like me, who did important things,” Smith Zrull said. “I think more women need to know, you’re not alone, you can do it.”

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story spelled Williamina Fleming's name as Wilhelmina.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?