Adios, vaquita marina? Mexico’s ‘little sea cow’ is being pushed to the edge of extinction.

The vaquita marina is a critically endangered porpoise species that lives only in the northern part of the Gulf of California. Scientists believe the population may be down to just 30 animals.

It’s just in the wrong place at the wrong time, except it has nowhere else to go.

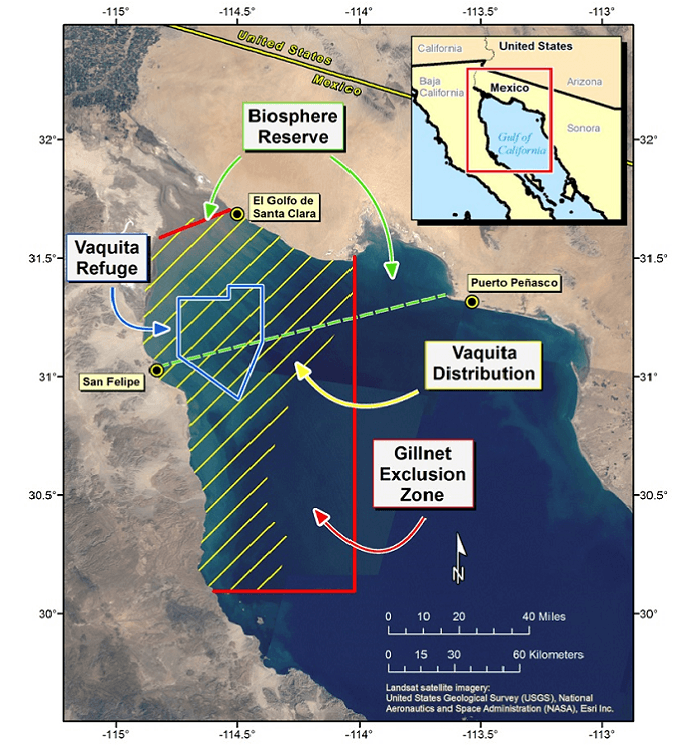

The vaquita marina — the little sea cow — is the world’s smallest porpoise. It lives only in the far-northern Gulf of California, just east of Mexico’s Baja peninsula, right where local fishermen are in hot pursuit of a very valuable creature. And its unfortunate fate has it on the brink of extinction.

“The vaquita marina [is] a source of pride for many in Mexico,” says American marine biologist Peggy Turk, who works on the Gulf of California. It’s a knobby-nosed creature about 4 and a half feet long, with clown-like dark accents around its eyes and mouth. It’s a very shy animal that few people have ever seen alive. And it exists nowhere else in the world.

“Nobody wants to kill the vaquita,” Turk says. “It just happens to live in the same place that fishermen are fishing with gill nets.”

What they’re fishing for is another endangered species — a mammoth fish called the totoaba that can weigh as much as 200 pounds. Many Chinese believe the totoaba’s swim bladder has medicinal powers, and they’re worth big bucks in Asia. A single bladder can sell for up to $10,000 in China.

It’s illegal to catch totoabas, but the temptation can be irresistible. And the gill nets local fisherman use to snag them also trap and kill other marina life, including the vaquita. After years of this fishing, scientists now estimate there are as few as 30 vaquitas left.

Mexican authorities have created a no-fishing zone in the area and imposed a temporary ban on gill nets, which environmental activists are pushing to make permanent. Across the border, the US Attorney's office in San Diego has cracked down on smugglers who ship totoaba bladders from US ports to Asia. Since 2013 at least seven people have been convicted and more cases are pending.

Still, illegal fishing continues. In the past year, the marine activist group the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society reports pulling more than 200 illegal nets from waters of the no-fishing zone.

“Many fishermen have no choice but to turn to illegal fishing,” says Marcos García, a lifelong fisherman who lives in the local port town of Puerto Peñasco. “Amongst ourselves we ask, ‘who will disappear first, us or the vaquita?’”

García says the no-fishing zone has hurt local communities, some of which rely almost entirely on fishing. Mexico funds a compensation program for fisherman, but García says it’s rife with corruption.

The situation has created a climate of tension and fear among locals.

Government inspectors charged with patrolling the no-fish zone weren’t authorized to talk, but say they’re being watched by what they call “bad people.” In March a mob of angry fishermen reportedly set fire to their patrol cars and boats. Some of the inspectors were physically beaten.

Meanwhile, out in the waters of the gulf, time is running out for the vaquita marina. In a last-ditch effort to save the species, Mexico announced in January that it will capture some of the porpoises and hold them in a sea pen until it’s safe for them to return to the wild.

This story was produced with support from the International Women’s Media Foundation.