South Africa’s imperfect progress, 20 years after the Truth & Reconciliation Commission

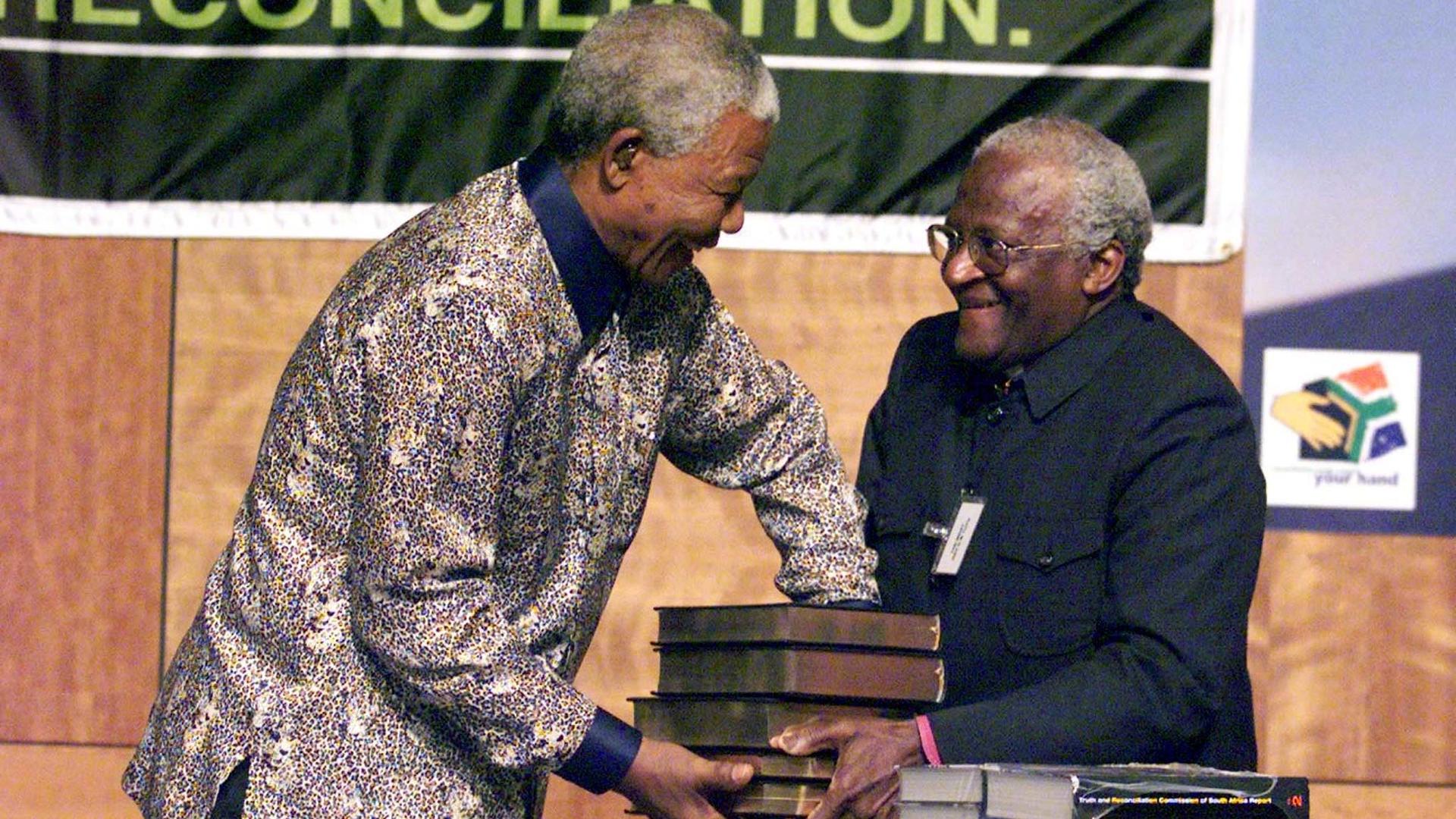

Chairman of the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) Archbishop Desmond Tutu (R) hands over the TRC report to South Africa's President Nelson Mandela at the State theater Building in Pretoria on Oct. 29, 1998. South Africa's Truth Commission found that the ruling African National Congress is politically and morally accountable for gross human rights violations committed during its 30-year struggle against apartheid.

The gold standard for how a divided society with a violent past might work through that past and move forward was set 20 years ago by South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, inspiring other similar efforts around the world, even as the country has learned over time that working through a complicated past takes time, and is still taking time. It opened up a way to talk about the individual and systemic wrongs committed under 43 years of apartheid, a government-imposed system of discrimination and separation based on skin color.

Over seven years, from 1996, some 2,000 people, perpetrators, and victims told their stories of what they’d done or what had been done to them, under apartheid. Over 7,000 perpetrators asked for amnesty; fewer than 1,000 got it. Those who did generally showed contrition, sometimes directly to family members of the people they’d killed.

All this testimony was broadcast live, and all around the country, people watched. Some wept. Some scoffed. Some knew these stories all too well. And some were hearing them for the first time.

“The commission was an amazing project, well-conceived. It did sterling work,” says Stan Henkeman, executive director of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation in Cape Town. “[The Truth and Reconciliation Commission] was led by one of the foremost personalities in the country. And it actually was representative. There were even people on there with right-wing leanings. So the commission itself was a great institution.”

That said, the TRC had its flaws, Henkeman says. Not everyone with a grievance had a chance to be heard — the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation is even now, 20 years later, trying to help some such cases get to court. And, he says, far too few of the perpetrators who were denied amnesty were ever prosecuted for their crimes.

“The government and particularly, the criminal justice system, failed the people of this country in terms of the amnesty process,” he says. “And you can imagine what it does to somebody whose family member was killed by somebody, and they can see that person walking around.”

And then there’s the almost inevitable reality that the initial euphoria after the end of apartheid has been tempered by time and experience, and some disappointment, as Mandela’s leadership and vision haven’t been matched by his successors. An opening of South Africa’s economy, after the lifting of sanctions imposed because of apartheid, doubled the country’s per capita gross domestic product and moved more black South Africans into the middle class, but still disproportionately advantaged the country’s white population. And while more colleges and businesses have opened up to nonwhites, with affirmative action quotas in place to ensure they do, disparities in income and opportunity remain stark, especially outside of South Africa’s major cities.

“There was a moment I remember,” says Sandiswa Sondzaba, a black 22-year-old master’s student in geography at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “I went to an elite, girls high school, and we volunteered to teach a 6th-grade class in a rural black community. We asked one student what two times two is, and the student didn’t know.”

At her own university, she says, she’s seen that the rural and township students who make it that far too often “disappear from the system because of economic struggles.”

“The government has spoken about looking for funding for the missing middle … but if people are starting with debts when they graduate, which is also a problem in America and in other developed countries, how are they supposed to help their families with accessing upward social mobility?”

Sondzaba says her own family has done OK, post-apartheid, but they started out ahead — Sondzaba's mother has two master's degrees.

“So we managed to gain some sense of upward social mobility,” she says. “But you still kind of see when you’re out with your friends from different racial groups, you’re kind of expected to assimilate. As a black person, you’re expected to speak in a certain way, to come across as intelligent. If you speak with a black accent, you’re seen as less intelligent than someone who speaks with a European accent.”

One group in South Africa that felt disadvantaged both during and after apartheid is those categorized as "colored" — mixed race and/or descendants of the indigenous Khoisan people. They used to make up the majority of Cape Town’s population; in the 1950s, they were forced to move to the outskirts of the city, to areas known as the “Cape Flats.” A downward spiral of poverty, crime, gang violence, drug use and teen prostitution ensued and remains a problem in many such areas.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

“I was sitting around with friends when I was in grade 11, and the crystal meth was all around me,” says Chantay Hayes, 27, a resident of the Elsie’s River community in the Cape Flats. “They were trying to get me to use some of it, and I just refused. I just clearly had a choice to make, and that was my choice. I chose not to do it.

But many of her friends did.

“There are a lot who have passed away, because of the drugs,” she says. “Some of them are still on it and alive, but they look very, very unhealthy and sick. They have a lot of children. They don’t work. They steal. It’s actually very, very sad to see them like that.”

Hayes found a way out. After spending some time in the United States, she’s now employed by an American doctor, working in Cape Town. She has a car. She goes to work. Her old friends and neighbors aren’t sure what to make of her life.

“When they see me drive around with the car that I have, or they see how I look, I’m healthy and I’m looking after myself, they either think I’m dealing drugs, or I’m doing some sort of illegal activity,” she says with a sad smile. “It’s that rare here for someone here to get a normal job.”

Part of the reason, she says, is that the affirmative action quota system now in place actually makes it harder for those in Cape Town’s colored community to get jobs and university admittance close to where they live. That’s because the quota for colored students or employees is 9 percent — the proportion of colored people in the South African population as a whole, while more than 40 percent of Cape Town’s population is colored.

"It’s a vicious cycle," Hayes says. "They can’t get into college, these very intelligent guys who are living around here. They will come and do odd jobs. They will fix your car. They will fix everything, so they can buy crystal meth. They can’t get the jobs they always wanted, so they will do odd jobs so they can numb the pain, and then they’ll buy crystal meth just to forget about all their problems."

And that can lead to other problems, like getting drawn into gangs. Gang violence in Elsie’s River has become a fact of daily life; Hayes says murders are a regular occurrence, with gangs sometimes getting preteen boys to carry them out. And when violence happens, she says, the police rarely come.

“Sometimes, we think they’d just like the colored community to kill ourselves off,” she says. She and others at Elsie’s River say there seems to be a lingering resentment from black South Africans toward the colored community because white South Africans gave the colored community a few more privileges than blacks under apartheid. That didn’t always count for much, even then.

“When I was 8 years old, I saw my friend getting killed in front of me because of racism,” says Brendon Adams, also a colored South African who grew up in Elsie’s River. “This huge, white policeman just started beating on both of us. I got away so I’m here to tell the story. And unfortunately, he didn't make it. … That’s when I realized that something is off in this world. And I couldn’t do anything about it.”

As a teenager, Adams did start to do something — he joined street protests in the last years of apartheid and watched as fellow protesters near him were killed, wounded or detained by police.

“Believe me, you’d rather be killed than detained,” he says. “I know people who were tortured by the police, and they’re still traumatized, even now.”

When apartheid ended and the Truth and Reconciliation process started, Adams says he thought it would genuinely lead to a united South Africa. He's disappointed that the colored population, in particular, has been left behind, effectively ghettoized, at least in part. "President Mandela told us back then that if the ANC [African National Congress, still the ruling party] ever treats us the way the apartheid government did, we should get rid of them. Well, it seems like that's the case, now." Adams now lives in Minnesota, where he drives a school bus and teaches gospel music, but he comes back regularly to Elsie's River to help the New Hope Jeremiah Project for which he once worked, providing after-school activities and meals to kids in the community and encouraging them to steer clear of drugs, gangs and prostitution, and think instead of creating a better future for themselves.

For all these entrenched problems that remain in South Africa, made no better by what many South Africans consider ineffectual and corrupt governance under President Jacob Zuma, most agree that life now is better than it was two decades ago, and that communal experience of watching and learning from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work was a big part of what made the improvements possible.

“I remember when we were watching it, and it was, for me, absolutely shocking to hear what black people went through when they testified about the killings and all those things that happened,” says Jan Snyman, 70, an Afrikaans-speaking former government official and diplomat under apartheid. “And so the lasting effect was, I think many complained to say they didn't go far enough. But I think it was a good start. It was a good start to get it out, to tell people what was happening.”

Snyman grew up in the exceptionally segregated Free State, the grandson of a farmer who fought in the Anglo-Boer war and the son of a Dutch Reformed Church minister. He says he played with black kids when he visited nearby farms, but didn’t think much, “to my shame,” about why their families were living in mud huts while he and his friends were living in comfortable houses. He says he started thinking more critically in college, and more again when, working in the government’s information department, he accompanied an Australian journalist in 1973 to interview Nelson Mandela in prison on Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town.

“You know, everybody always said that when you meet Nelson Mandela, it was just like a different atmosphere, because of the personality that he was. And I experienced that, exactly that,” Snyman says. “And the things he was saying then were the same things he said when he got out of jail in 1990 — the vision of having democracy, equality, one vote for each person.”

Snyman says he was impressed with Mandela’s leadership, and with what he made possible for South Africa. Twenty years later, even if not everything has gone as well as hoped or expected, Snyman is one Afrikaner who thinks South Africa is better for having given up apartheid and gone through the Truth and Reconciliation process.

"Should they have gone further? Should many people have gone to jail? I think one or two did, of the terrible things that they've done. But it was certainly an eye-opener. And people can accuse me, how did you not know? That's fine. Then they can accuse me. It's because of the system, and where I grew up — no one really talked about how all this worked. I think it was a shock to many Afrikaners. And I think to a certain extent it helped, in terms of reconciliation. But it's going to take a long time."