Scientists make a battery that runs on stomach acid

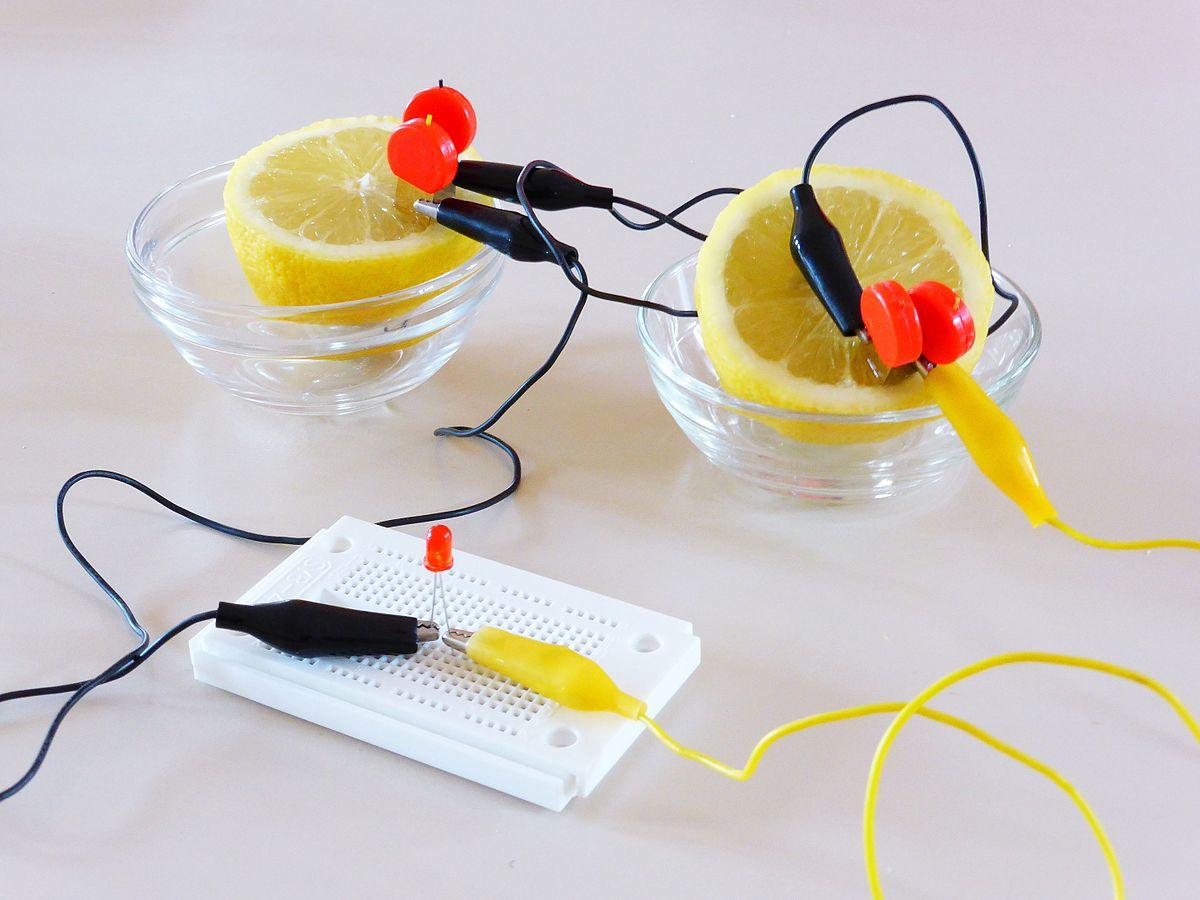

A “lemon battery” is pictured here. Using lessons from the kid-friendly experiment, scientists have developed a battery that runs on stomach acid.

A new wave of “ingestible electronics” is poised to transform health care from the inside out. Researchers are experimenting with sensors that can wirelessly monitor vital signs like heart rate, respiratory rate and body temperature from the squishy interior of our gastrointestinal tract.

But for the devices to work longer than just a few hours after we swallow them, they need batteries that can safely be used inside our bodies. Now, researchers at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital have a solution: They’ve developed an ingestible battery that runs on stomach acid.

It’s modeled on the “lemon battery,” the time-honored science fair project that uses the acid of a lemon to react with connected metal electrodes, generating electricity.

“We started exploring a couple of ideas and … thinking back to the high school days, one of the concepts was applying the lessons from the lemon battery,” says Giovanni Traverso, a gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He was a lead author on the earlier sensor research and co-authored this new study.

In the study, the battery powered a wireless temperature sensor in pigs for an average of 6 days.

“Before this worked, the longest that had been achieved through systems was more on the order of minutes to about an hour,” Traverso says.

What’s more, the battery worked while pigs were eating and drinking — “going about their daily business,” he adds. And as the battery passed out of the stomach and into the small intestine, it kept harvesting small amounts of energy, even though the intestine isn’t an acidic environment. Traverso calls it an “encouraging observation” for other body systems.

Eventually, Traverso and his team hope to develop a battery that can power sensors for weeks, and even months, after ingestion. He says that in the next phase of research, the team will likely dig deeper into how diet affects the battery’s energy harvest. “Specifically, you know, how much energy is available to be harvested during those times of feeding versus ones during a fasting time.”

The pill housing the battery and sensor will see some changes, too. “This was a prototype,” he adds. “And it was on the larger side.”

In the future, Traverso thinks the pill could be designed to remain in the stomach for a prolonged period of time, and then change shape to trigger movement through the body. It could also be made out of materials that dissolve after a certain amount of time, delivering medications more effectively.

From there, Traverso sees a plethora of possibilities for the pill. “The first thing we showed here in this study was temperature,” Traverso says. “But we've done some other work in the past looking at measuring heart rate, respiratory rate. And we're doing some other work looking at movement of the actual [gastrointestinal] tract, and then sensing different proteins and toxins.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.