Chile’s forest fires have been raging for weeks. What caused them?

A firefighter removes the remains of a burned house on a hill, where more than 100 homes were burned by a forest fire in Valparaiso, Chile, Jan. 2, 2017.

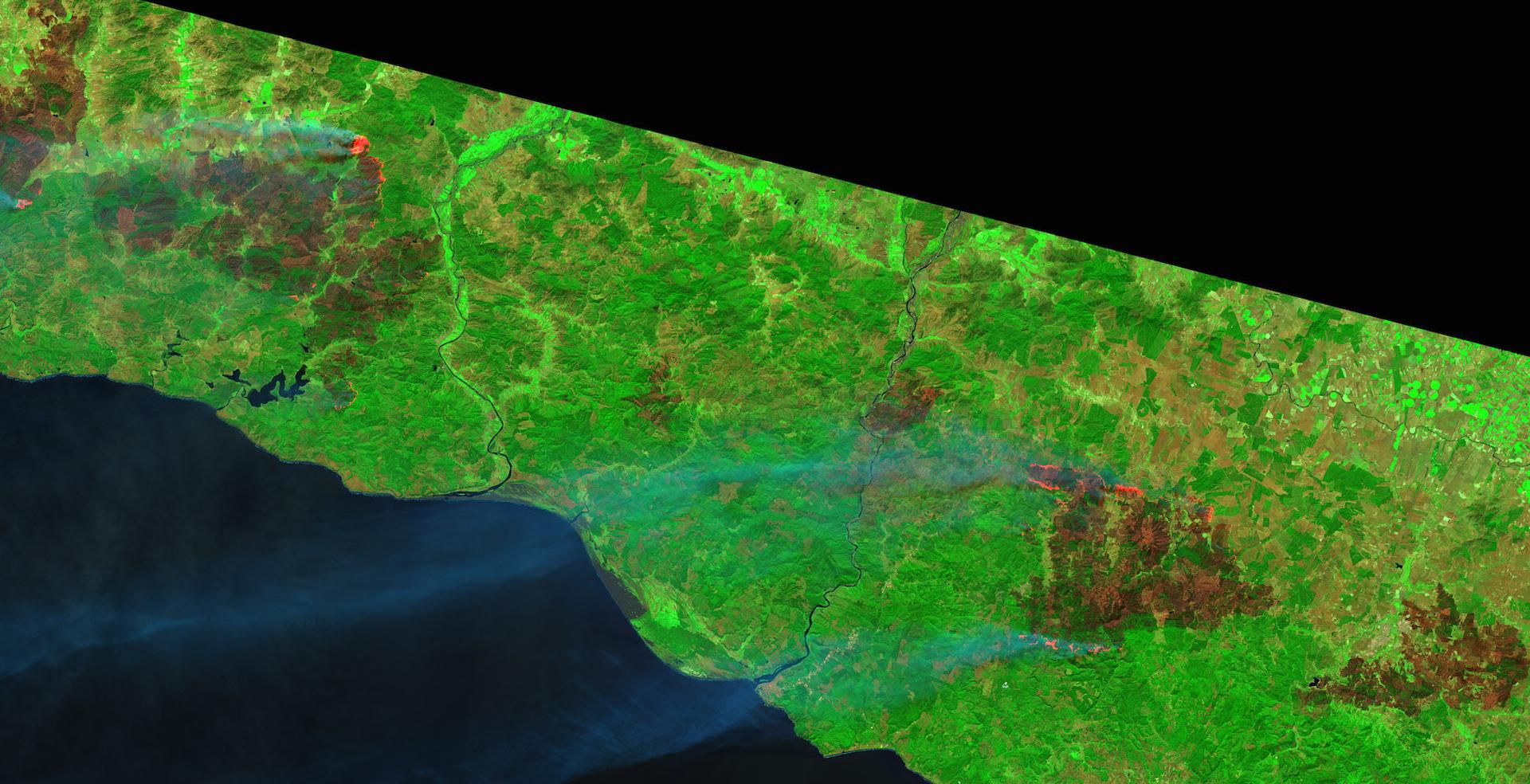

It started with a burst of flames in the steep Chilean hillsides of Valparaíso, two days after crowds celebrated New Year’s. Then flames started popping up farther south. Since then, almost 100 fires have burned hundreds of thousands of acres across the country.

A month later, many of the fires are still burning in what President Michelle Bachelet has called the “greatest forest disaster” in Chilean history.

The blazes have killed at least 11 people and wiped out homes, pasture and livestock, leaving a total burn scar about the size of Delaware.

President Bachelet says some fires were likely started deliberately and others were accidents.

But while authorities investigate, many Chileans are shocked by how underprepared the country seemed — especially since this is the second time in three years that massive fires have hit Valparaíso.

The government has continually increased the annual budget for the privately operated National Forestry Corporation, which manages fire emergencies and goes by the Spanish acronym CONAF. And yet, residents say the corporation arrived too late. They say locals got little help from the municipal government, and volunteers were left to do much of the initial firefighting.

Five days of raging fires in late January destroyed almost 100,000 acres in the south-central regions of O'Higgins, Maule and Biobío, which are leading timber and pulp producing areas that consume a lot of water.

That’s when Bachelet declared a state of emergency and deployed the military. Countries around the world began to answer her call for assistance.

The destruction of almost 1,500 homes is estimated to cost the government $333 million, Voice of America reported, citing Chile’s finance minister.

The disaster began while many Chileans were enjoying the holiday season. But Cristóbal Weber, a 19-year-old from the Maule region, felt compelled to volunteer to fight the fires in the town of Curepto.

“I’m still impressed by how many people came together to help out,” Weber says.

Another volunteer was Felipe Ponce, 35, who has land around the Navidad area in O’Higgins. “The fire was spreading over pine and eucalyptus lands. It was all dry,” he said, after pointing to pictures and videos he took there.

While the number of fires has been greatly reduced, they have yet to be fully controlled as of Friday, Feb. 10. More than 20,000 people were at work against the blazes — even water-spraying police tanks used at protests are putting out fires.

“It’s a radical change to see a different face of the guanaco [a slang term for the tank]. Great to see a repression tool actually being useful for society,” said Daniella Mundy, a psychologist and social worker in Santiago.

But the forestry corporation has taken a lot of flak for its response.

A foundation in the US deployed the “Super Tanker,” the world’s largest firefighting plane. But it remained on standby for three days, awaiting the forestry corporation’s approval, in the midst of the country’s chaos. Once the company’s director agreed, he subjected the aircraft to a two-day trial to test its usability in Chile — sparking outrage and disbelief.

“Hearing CONAF’s director say the airplane would not work here is enough to come to conclusions about the corporation,” said Christian Venegas, a risk prevention engineer who was a former security officer for CONAF. He claims the corporation is not qualified, equipped or prepared to do its job.

A current company employee interviewed for this story agrees.

Sergio Agüero, the CONAF workers’ union director in the Los Lagos region, says new brigadiers receive just four days of training. “On top of that, no one knows what life insurance they’ve got. Workers use uncertified gear for firefighting. Even worse, a brigadier had to die for CONAF to replace hiking shoes with professional boots,” Agüero says.

Fernando Rain, another former official at the corporation, says the company has discouraged using large firefighting aircraft in the past, claiming they won’t work in Chile's terrain. He says that’s a result of the agency’s experience battling Valparaíso's infamous 2014 fire. “There was lack of coordination and planning when a Brazilian plane got there. CONAF officials basically sent it out to dump water everywhere, and not where it was needed.”

The National Forestry Corporation did not answer requests for comment.

Residents are concerned that maybe they were neglected.

“There was a fire whichever direction you looked to simultaneously. I don’t want to think that they let us burn, but after analyzing the situation, I really don’t know,” said Erica Aravena, 57.

Aravena lived in Santa Olga — the largest town turned to ash — and teaches kids in nearby Empedrado. Her family was among the first to populate the town back in the 1970s. She was lucky to make it out.

"My daughter and I had a bag ready because the fires were getting worse. We took that and left with the hopes of coming back, but that's impossible now, it's all gone. Nothing of our house is left, absolutely nothing,” she said. “Fortunately, the school I teach at was spared. But most of my students are homeless.”

Some blame record-high temperatures, droughts and winds for helping prolong the fires.

Investigations are ongoing, and at least 47 people have been detained on suspicion of arson.

Meanwhile, conspiracy theories — blaming everything from timber companies to foreign terrorists — are running wild online.

One Facebook video garnered over half a million views in only five days. It theorizes that Chile’s top two timber and pulp companies are behind the fires. Some have blamed ISIS, the FARC or the ETA. Others have fueled discrimination by pointing to Mapuche indigenous people or Colombian nationals as the culprits. The Colombian immigrant population in Chile has sharply increased in recent years.

Chile’s president and attorney general have advised the public to ignore internet claims while they investigate the fires’ causes.

Agüero, the union leader, claims 99 percent of fires are man-made.

“Chileans know what it’s like to live with constant earthquakes and other natural catastrophes, but it takes getting used to human-induced disasters like the one in Chiloé,” said Mundy, the psychologist. “Though Pinochet-era terrorists are gone, maybe he set the legal foundations for a different kind of wrongdoing.”