As California considers a ‘sanctuary state’ bill, this sheriff isn’t ready to give up his relationship with immigration agents

When Thomas Homan, left, acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, participated in a town hall in Sacramento on March 28, 2017, things got loud. Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones, on the right, says he was satisfied with the event, though.

Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones tried to quiet down the boos, jeers and cheers. But just 30 seconds into his opening speech to a boisterous crowd, someone shouted, “Fuck you!”

This was how an immigration forum played out in late March in California’s capital city. Hundreds of people — residents, protesters, public officials and journalists — packed into a large school gymnasium in Sacramento. When Jones spoke, protesters interrupted. They called him a liar and shouted other expletives. Meanwhile, his supporters cheered and clapped whenever he mentioned enforcing laws.

At the center of all the discord were Jones and Thomas Homan, the acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). That’s the federal agency charged with enforcing immigration laws, including detention and deportation.

“This forum is not to make everybody get in the same page and leave here in agreement,” Jones said in his opening remarks. “This forum is for the simple purpose to try and provide factual information about what we do in law enforcement in the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department, and by that, what law enforcement in California does and what ICE does or does not do in the communities.”

In Sacramento, two agencies are at odds when it comes to implementing the President Donald Trump’s controversial immigration policies. At the forum, this divide was on display.

On one side is the city of Sacramento, which maintains a so-called “sanctuary” status. On the other side is Sacramento County and its Sheriff’s Department, which has a contract with ICE to detain immigrants on its behalf.

Jones invited Homan to Sacramento and came up with the idea for the forum after speaking with community members. He says he wanted to dispel rumors about immigration enforcement and to quell growing fears from immigrant communities.

But immigrant advocates says the forum had the opposite effect. The very presence of ICE’s top official in the city only exacerbated those fears and feelings of mistrust. Hundreds of people showed up to the event.

During the question period, the first time Homan has answered direct questions in a public meeting, attendees did not hold back.

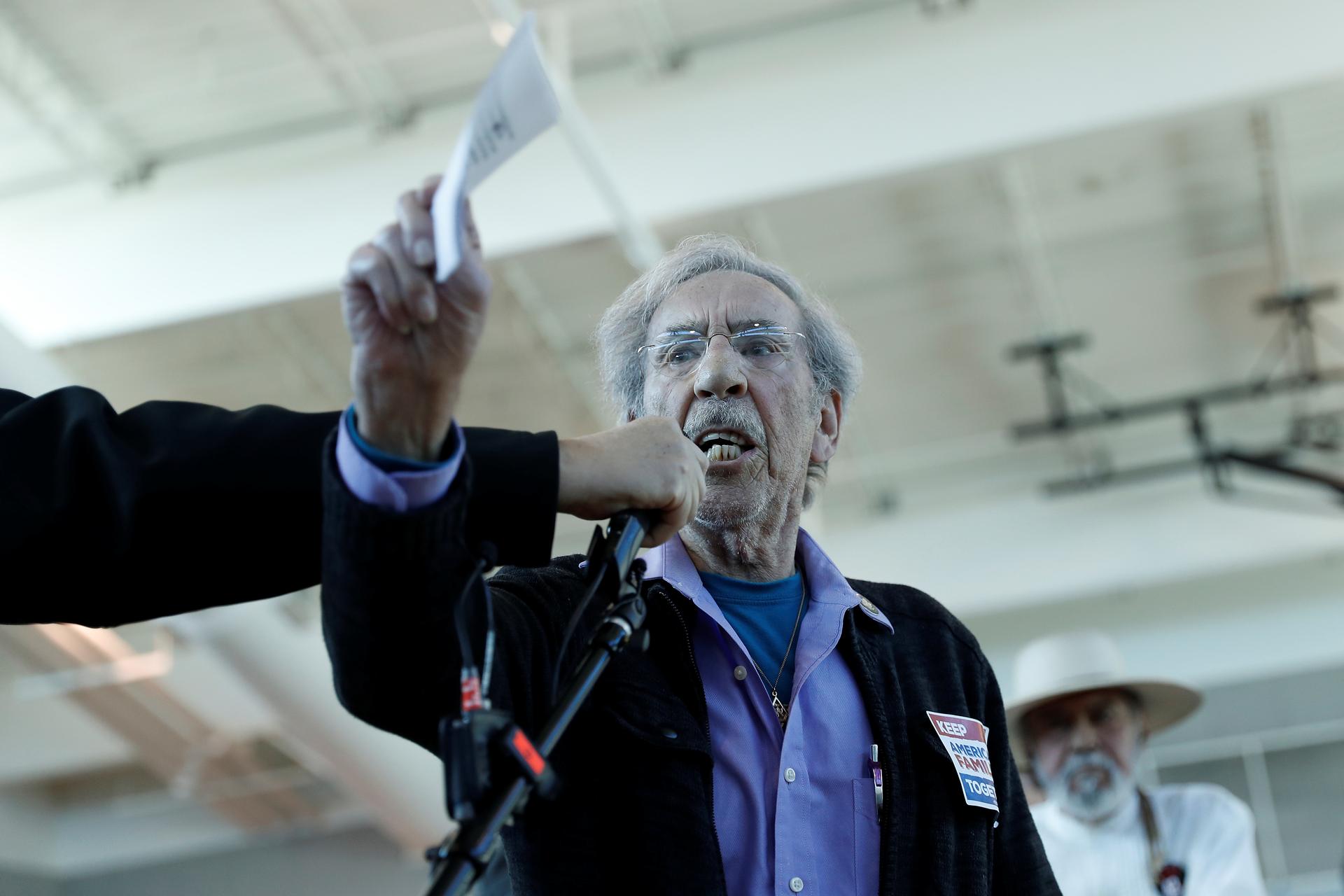

Among them was Bernard Marks, a Sacramento resident who survived a Nazi concentration camp. He told Homan and Jones, “History is not on your side.” His comment was met by booming cheers.

Jones listened to all of the comments, holding a microphone in one hand, his other hand sometimes in his pocket. He stayed calm in the midst of the commotion. Eventually, he asked deputies to escort out a group of activists who refused to stop yelling. They wore white T-shirts that spelled “ICE OUT” in red paint.

Homan also stayed on, unrattled, and maintained that ICE conducts targeted operations looking for specific individuals who are threats to public safety.

Also: How a community in Ohio is stepping up when deportations split families

Before the forum, city officials and activists held a protest. Among the speakers was Sacramento councilman Eric Guerra.

“What we want is for our federal government to do its job," he told the crowd, “and figure out the real solution to this — and that’s comprehensive immigration reform and not fear mongering, not scapegoating — to get to work and solve the real issues.”

Jones laments the media’s intense focus on the protesters. Overall, he says he was satisfied with the forum, even though it got rowdy. Every major media organization in the area covered the event and Jones proudly points out that thousands more watched the livestream.

“You had an unprecedented opportunity, for the local law enforcement executive in the region with the national director of ICE, so there are no greater sources of information about what's real and what's not real,” he says. “For the folks who were actually there to hear that. … I think it was very good.”

But Guerra, saw the forum differently.

“The process in having this conversation not only created more fear and animosity in the community, but I think also disrespected what we've been trying to do in Sacramento, which is connect the community and try to solve these issues,” he says.

The city of Sacramento currently has a 1985 ordinance that prevents city officials, including officers with the Sacramento Police Department, from asking individuals about their immigration status, making the city one type of sanctuary.

Also: America's sanctuary communities are more numerous than you think

But Sacramento, the city, is in Sacramento County, where the sheriff also operates. Jones says his agency does not enforce federal immigration laws. But he is resolute that his department maintain its relations with ICE.

“We never ask about immigration status,” Jones says. “But we have the burden of keeping people safe from the dangerous people that are in our jails and for that, there’s no way around a direct relationship with ICE.”

City officials question that relationship.

“We are not here to harbor any violent criminals — we want them out,” says Guerra. “But we care about not separating families.”

But there may be some common ground between city and county.

During a run for the 7th Congressional District in 2016, Jones advocated for secure borders and a pathway to citizenship for those who are already in the country illegally, but are law abiding. Jones also said that he wouldn’t deputize local law enforcement to enforce immigration laws.

But Jones also said he will continue his department’s policies, including an agreement with ICE to detain immigrants at the Rio Cosumnes Correctional Center. The Sheriff's Department reports that they detained between 250 and as many as 300 people per month in 2016. In the fall of 2014, they detained as many as 480 people on behalf of the federal immigration agency.

Critics are suspicious about the financial arrangement between the county and ICE, but Jones says money is not the motivation for the contract. Just one percent of his total budget, about $4.8 million out of $450 million, comes from ICE, he says.

“It's not going to make or break me. It ain't about the money. It's about helping a law enforcement partner because they don't have ICE jails in California.”

The future of Sacramento County’s relationship with ICE could depend on the so-called “sanctuary state” bill, which passed the California Senate and is currently in the state Assembly. SB 54 would prohibit local resources from being used to help federal agents in immigration enforcement.

Jones worries it will prevent his department from notifying ICE about dangerous criminals who are already in the county’s custody.

“The proponents of that bill are always going to want to talk about the first group of folks in our community, the hardworking men and women that want nothing more than access to opportunities,” Jones says. “We are all in agreement about those folks. They won’t want to talk about the folks in the jail, and that’s all I want to talk about.”

Recently, a federal court handed a victory to cities that consider themselves sanctuaries. A judge blocked the Trump administration’s executive order to strip federal funding from sanctuary jurisdictions while a case against it is heard in court.

The city of Sacramento will vote to update its 1985 ordinance on Thursday. It’s also looking at another proposal that would create an education and legal defense fund for undocumented immigrants.

Jones says he’s fine with the city’s efforts to be a sanctuary, though he doesn’t agree with it.

“But by that same token, they should stay out of my business,” he says. “And just be confident the fact that I've spent my entire career keeping Sacramento County safe and I know the best way to do that.”

More: Texas police may soon act more like federal immigration enforcers