50 years ago, MLK spoke out against Vietnam. His words are just as relevant today.

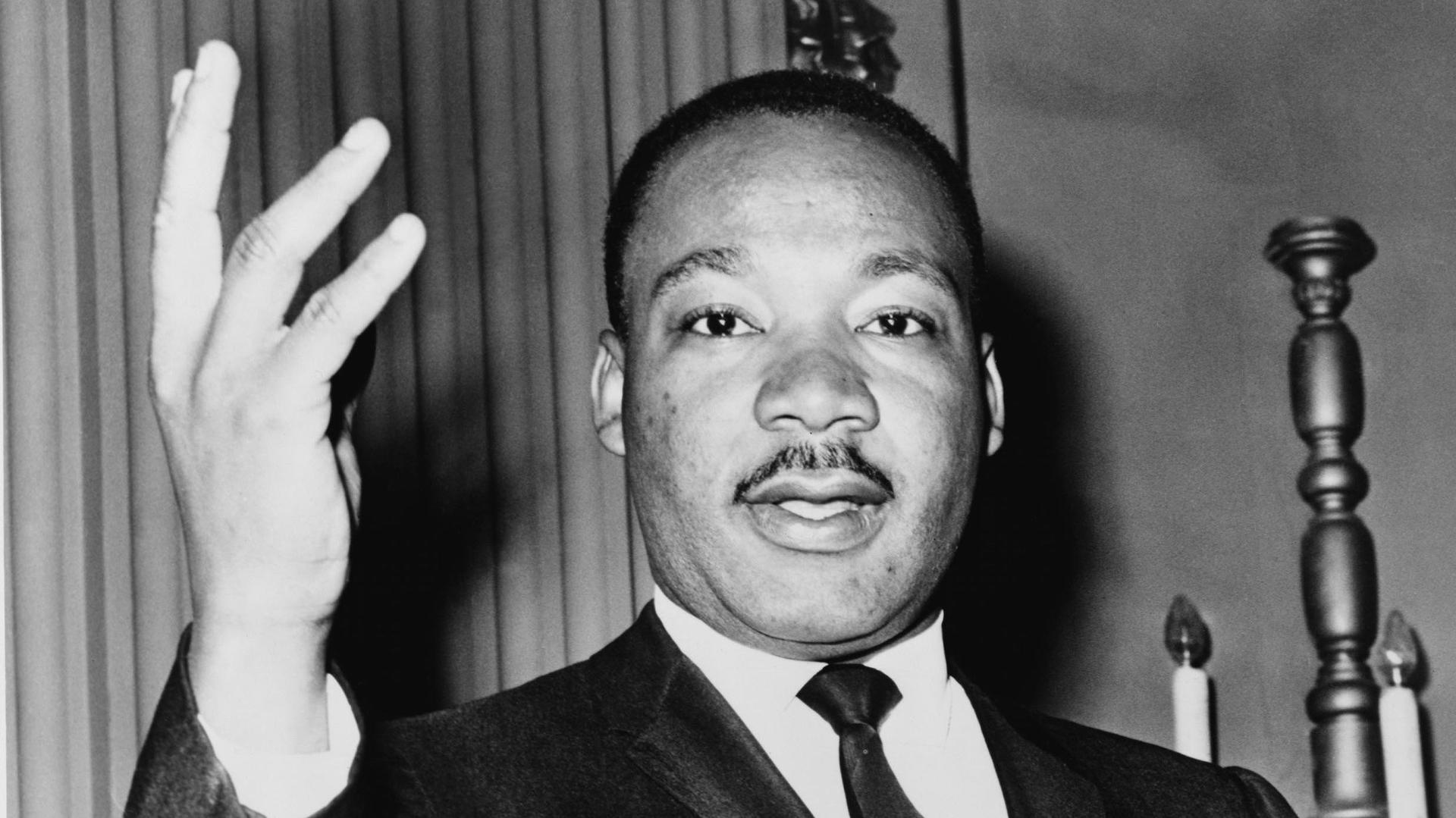

Martin Luther King Jr. is shown speaking, here.

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were allies in the fight for civil rights in America. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made it through Congress because of Johnson’s ability to bring lawmakers together, and both laws became absolute necessities because of King’s global movement for equality.

Recorded phone conversations between King and Johnson (click on the "play" button above to hear a few audio clips) show the evolution of a working relationship that made great strides in America's pursuit of racial justice. But in 1967, King chose to risk that partnership to oppose a view of American glory and honor that the president was fighting for overseas.

King, a civil rights leader at home, could not ignore what was happening abroad, and on April 4, 1967 — 50 years ago today — King spoke before a packed crowd at the Riverside Church, a focal point of activism in New York's Morningside Heights neighborhood. His speech was called "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence,” and it was his first major public statement against the war.

“Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war," King said during his address. "If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read 'Vietnam.'"

This was a huge risk for King. The speech was met with controversy and condemnation. Some 168 newspapers across America denounced his position, and The New York Times ran an editorial titled "Dr. King's Error."

But King was steadfast in his belief that if he were to be a civil rights leader in this country, representing the cause of those marginalized and brutalized by poverty and racism, then he must continue his commitment to stand against violence of the oppressed, even when the oppressed were more than 8,000 miles away. Justice was justice.

“We have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools," said King. "So we watch them, in brutal solidarity, burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor."

The speech marked a turning point in the relationship between Johnson and King — it triggered a break that could not be rectified. Their calls grew less frequent, and there is little record of their conversations after the 1967 speech. Johnson had always wanted to know how King viewed the war, but during a 1965 phone call between the two, you get a sense that even Johnson understood that the contradiction between war and civil rights was unsustainable.

“They all got the impression too that you’re against me in Vietnam,” Johnson told King. “You don't leave that impression. I want peace as much as you do, and more so because I'm the fellow that had to wake up this morning with 50 Marines killed.”

“He had been terribly disappointed in King for good reasons or not," said Harry McPherson Jr., special counsel to Johnson, in a 1968 interview after King's death. "King had become increasingly anti-administration, particularly on the war."

This sentiment also resonated with James Forbes, senior minister emeritus of the Riverside Church from 1989 to 2007.

“He was not naive about the impact of his taking on his government," said Forbes. “He made it clear that America would never be the great nation and could not keep faith with the Constitution itself … so it was a call for radical revisioning and restructuring of the whole system in the United States of America.”

Johnson decided later that year that he could no longer run for president and end a war that was tearing him and the nation apart.

Exactly one year after his Vietnam speech at Riverside, King was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Protest against the war continued beyond his death, and for many, his words from Riverside still hold true.

“I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken," said King. "I speak as one who loves America, to the leaders of our own nation: The great initiative in this war is ours; the initiative to stop it must be ours.”

Whose responsibility is it to recognize the contradictions of power and pursue the absolutes of human rights regardless of the cost? That question raised 50 years ago, today, has yet to be answered.

This story originally aired on The Takeaway. Archival material referenced in this piece came fromLBJ Library in Austin, Texas. You can listen to King's full speech from Riverside here.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?