His grandfather helped bomb Hiroshima. Today, he’s friends with a nuclear bomb survivor.

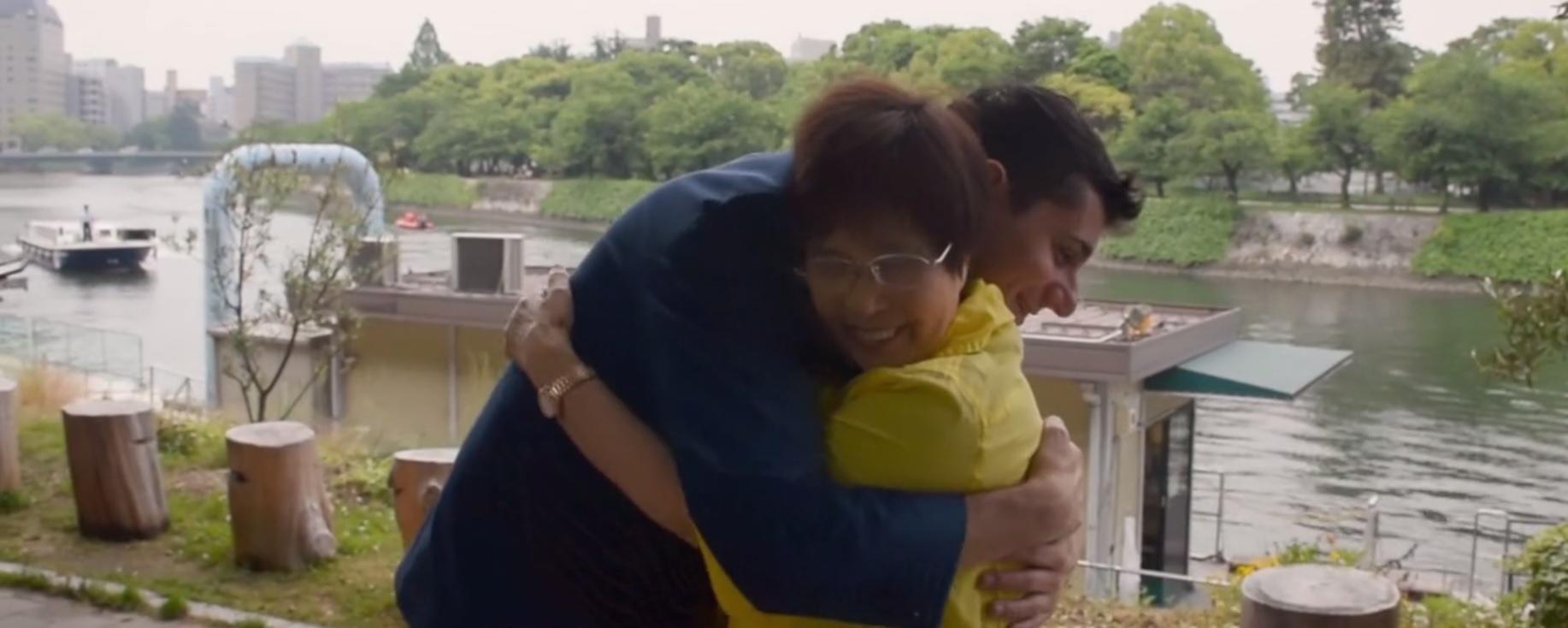

A film still from Ari Beser's documentary, "Hibakusha."

Six years ago, Ari Beser, a photographer from Baltimore, received a grant to visit the city of Hiroshima for the first time. He wanted to trace the path his grandfather had once taken. Jacob Beser, who died in 1992, flew over Japan as a member of the Army Air Force during World War II.

On the day that Beser got the grant, a tsunami struck the coast of Japan, flooding Fukushima nuclear power plant and causing an explosion and meltdown.

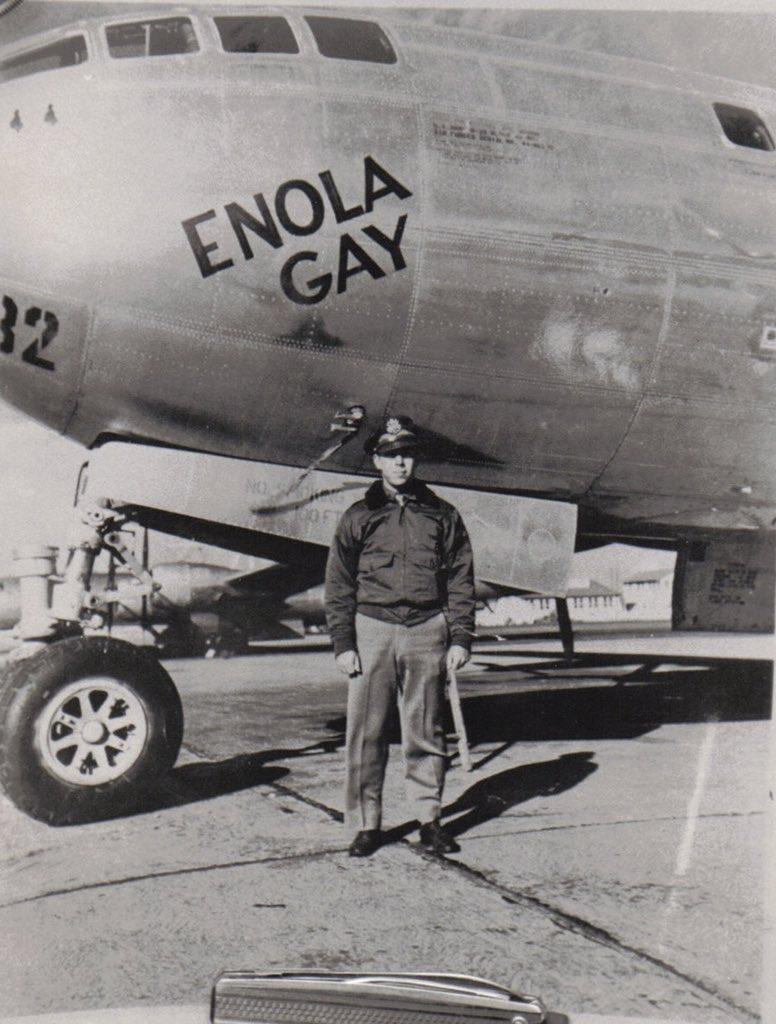

Beser thought about calling off the trip, but the timing was uncanny. Beser knew that nuclear technology of a different sort had brought his grandfather to Hiroshima in the first place. Jacob Beser was the only man in the world to fly on both planes that dropped nuclear bombs in Japan.

So Beser decided not to cancel his trip. Instead, he read up on his grandfather’s life. He found an old audio recording, in which Jacob Beser talked about manning the radar during the bombing of Hiroshima. “I never saw the intact city of Hiroshima,” the elder Beser said. “When I got to the window, all I saw was this boiling muddy mess, with fires continuing to break out on the periphery.”

Beser learned that his grandfather first joined the military because he wanted to fight against Nazi Germany. “My great-grandmother had been taking in German refugee children,” he said. The family had Jewish relatives in Europe, and the elder Beser felt a responsibility to either help them or avenge them.

“My great-grandmother wouldn't let him,” Beser said. “She said, you're a good Jewish boy. War is no place for a good Jewish boy.”

Then came Pearl Harbor. As 1941 came to a close, Beser’s grandfather joined the Army. He was sent to radar school in Florida and then to Los Alamos, where he joined a secret mission that was supposed to end the war. His superiors wouldn’t say what it was.

“They never said the word nuclear,” Beser said. “They never said they were building a nuclear bomb.”

Underneath the mushroom cloud

When the younger Beser flew to Japan in 2011, he was retracing the path his grandfather once took. In Hiroshima, he was surrounded by people his grandfather might have considered enemies. “If I went 70 years ago, I could have been killed. Just for being American,” Beser said.

During that trip, Beser spent several months in Japan. He took lessons in Japanese. He wasn’t just trying to understand his grandfather. He was trying to understand his grandfather’s impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese people.

“What I really wanted to learn is what it was like for the people underneath the mushroom cloud,” he said. “The women and the children that were mostly there.”

There are still thousands of living atomic bomb survivors — hibakusha, as they’re called in Japanese. One day, Beser went to a lecture by a woman named Keiko Ogura, who has worked as a volunteer translator for fellow survivors. She spoke at length about her own recollections of Aug. 5, 1945.

“I was on the road near my house, and all of a sudden there was a tremendously bright flash,” she said in a recent interview. “I couldn't stand, and then I couldn't breathe. I was hit on the road and became unconscious.”

When Ogura woke up, it was so dark that she thought it was evening. The sound of her brother crying brought her back to the present.

“I waited for a while, and then, by and by, I could see my neighborhood,” she said. It started to rain. The droplets were black and stained her blouse. All around her were wounded and dying people.

Ogura said that when the injured asked for water, she gave it to them. Some of those people died, perhaps from shock. “I thought it was my fault, and I blamed myself so many years,” she said sadly. “I saw very dreadful nightmares.”

'I have to tell'

There are many thousands of survivors like Ogura. For decades, few of them shared their stories. “I tried to forget those days, because it’s a horrible memory,” Ogura said. There’s not only trauma, but also stigma. Some Japanese people viewed radiation sickness as contagious. Others assumed children of survivors would be born with defects.

Ogura’s husband often shared stories of Hiroshima, through his work at a local museum. But Ogura didn’t even talk about her memories with her children. “So many years, more than 50 years I think, I didn’t talk about myself,” Ogura said.

Only when her husband died did Ogura overcome her reluctance. “I thought, I have to tell. I have to do something!” she recalled. “Because people do not know about Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

When Ari Beser heard Ogura’s lecture, he thought about his grandfather, who was far above the carnage in a B-29. The elder Beser didn’t feel remorse for what happened. After the war, he helped to establish Sandia National Laboratories and then worked as an engineer for military contractors.

Beser wondered how his grandfather might have reacted to stories of survivors in Japan, like Ogura. When she finished her lecture, six years ago, he went up and introduced himself.

In a recent phone conversation between Beser and Ogura, they shared their memories of that first meeting. “I was embarrassed that no one had explained to you beforehand,” Beser said. “You would maybe be surprised to know that instead of a regular American boy, you were talking to the grandson of someone who was on the airplanes. Someone who was above the mushroom cloud.”

Ogura remembered feeling excited to meet him. If anything, she was worried about how he might feel. “I felt so sorry,” she told Beser. “Weren't you shocked?

“It's more amazing to me that you were more worried about how I would feel, than how you felt,” Beser replied. “All you were worried about was somebody else.”

Ogura said that the meeting with Beser didn’t cause her any pain or anger. “I thought American young people should know what happened,” she said.

The encounter deepened Beser’s commitment to hearing and sharing the stories of survivors. He met with Ogura many more times, even spoke alongside her at events in Japan. In Japanese, she even nicknamed him “grandson.” In 2015, Beser published a book about their shared story. It’s called The Nuclear Family.

'That's the definition of peace'

In 2016, during a historic visit to the Hiroshima Peace Park, President Barack Obama met nuclear bomb survivors and prayed with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Beser was in attendance, and remembered having a kind of revelation.

“I just realized that one day, I’m going to tell my grandchildren that my grandfather was the only man in the world that flew on both the planes that dropped the atomic bombs. And their grandfather saw the first US president come to Hiroshima,” he said. “To me, that’s the definition of peace.”

Beser remembers seeing Ogura that day, too. They were happy.

“She said to me, your grandfather was above the mushroom cloud. And I was under the mushroom cloud. But we can be together.

What brought Beser and Ogura together was a bomb. A technology more destructive than any that came before it. But they hope their shared story can be as powerful as any weapon.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?