Japan: cooling pool nearly boils over at nuke plant

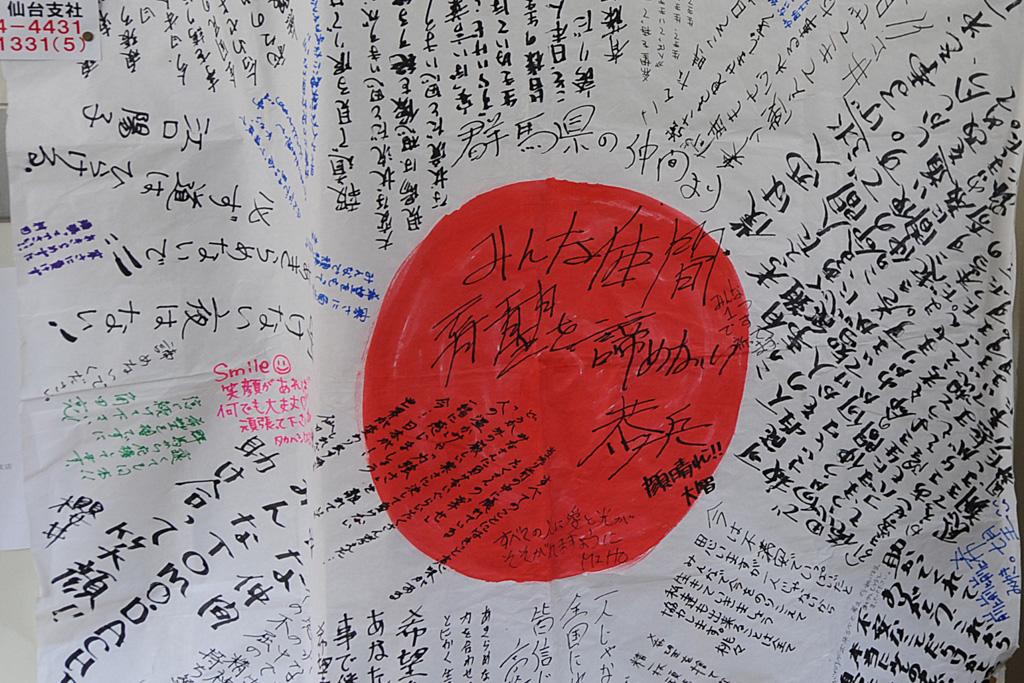

A flag of Japan with messages of hope and strength written by residents is posted at a primary school being used as an evacuation center in Ishinomaki in Miyagi prefecture on March 21, 2011.

TOKYO, Japan — A pool containing spent fuel rods at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant almost boiled over Tuesday, sending fresh tremors of fear among workers battling to cool it down.

The water began to simmer in the No. 2 reactor, one of two reactors that had to be shut down Monday after emitting smoke and steam. Workers returned to the scene, rotating in and out of the most critical area for carefully limited periods to avoid exposure to radiation through their protective gear.

Technicians have been able to perform on-again, off-again work on the stricken plant in the wake of the devastating earthquake and tsunami on March 11. Already the double-whammy disaster has claimed a confirmed 9,080 lives, according to the national police, and another 13,561 are still missing.

The water in the overheating pool on Tuesday reportedly cooled down enough for fire trucks to pour more seawater onto the reactors later in the day, but government officials did not seem to have a firm grasp on events.

“We are taking necessary measures” to create “a stable situation at a low temperature level,” said Hidehiko Nishiyama, deputy director of the nuclear safety agency. “We must take care of it as quickly as possible.”

The lack of electricity at the plant prevents officials from knowing exactly what is going on inside, Nishiyama said. “When we restore the supply of electricity, we will know for sure the actual situation and ensure measures are adequate to insure a sustainable cooling system,” he said.

Despite reports that power cables had been reconnected to all six of the affected reactors, the difficulties in reducing the temperature of the cooling pools made it impossible to shut down all the reactors.

Nonetheless, Nishiyama said a total nuclear meltdown was out of the question. “We do not,” he said, “anticipate the possibility of a meltdown.” Although the cores of three of the reactors have been damaged, officials believed they had contained the damage.

Concern, however, focused on the morale of the 700 to 1,000 workers, including engineers, technicians, firemen and soldiers from the Japan Self-Defense Forces, as they battled night and day to bring the episode to an end. All of them stay in an “emergency room” when not actively working to control the reactors.

“There have been ups and downs in terms of the numbers of workers on the site,” said an official. “When small fires take place, workers leave. As the situation stabilizes, workers come back to the site.”

Fears of radiation remained despite assurances that there was nothing to fear outside the 20-mile danger zone surrounding the plant. “Radiation continues to come out on an on-again, off-again basis,” said Shunichi Yamashita, a professor from Nagasaki University. However, he said, “the amounts recorded so far will not have an effect on people's health.”

Yamashita, talking at the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan, compared radioactive material from the Fukushima plant to “ash spewing out of an erupting volcano.” Like volcanic ash, he said, the amount being released “is getting smaller and smaller as is the area over which it's being spread.”

Yamashita said it was “wrong to say that even a trace of exposure would be dangerous.”

Against such assurances, however, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reported radiation levels at 1,600 times the norm on the edge of the danger zone. The Associated Press quoted Graham Andrew, a senior adviser to IAEA chief Yukiya Amano, as saying, "We are still in an accident that is still in a very serious situation."

Traces of radiation have spread to seawater — likely carried by vapors from the plant or by water running off the soil.

Seawater samples reportedly showed levels of radiation to be 126.7 times higher than the legal limit. An official was quoted by the Japanese news agency Kyodo as saying high levels of cesium and a trace of cobalt-58 were also found in seawater near the plant.

Local officials are confronting rising anger, much of which has been directed at the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (Tepco), which runs the quake-crippled plant.

Governor Yuhei Sato of Fukushima Prefecture, of which the city of Fukushima is the capital, made a point of refusing to meet the Tepco president. “There is just no way for me to accept their apology,” said Sato in a nationally televised interview in which he cited “the anxiety, anger and exasperation being felt by the people.”

Officials were especially sensitive to widespread criticism that Tepco had failed to conduct necessary safety inspections prior to the disaster, much less come up with permanent solutions for avoiding disaster “next time.”

Though, for the Fukushima plant, built 40 years ago, there is not likely to be a "next time." “After pouring sea water, it would be challenging to restart the reactor,” said a foreign ministry official.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!