India: Is China right about the internet?

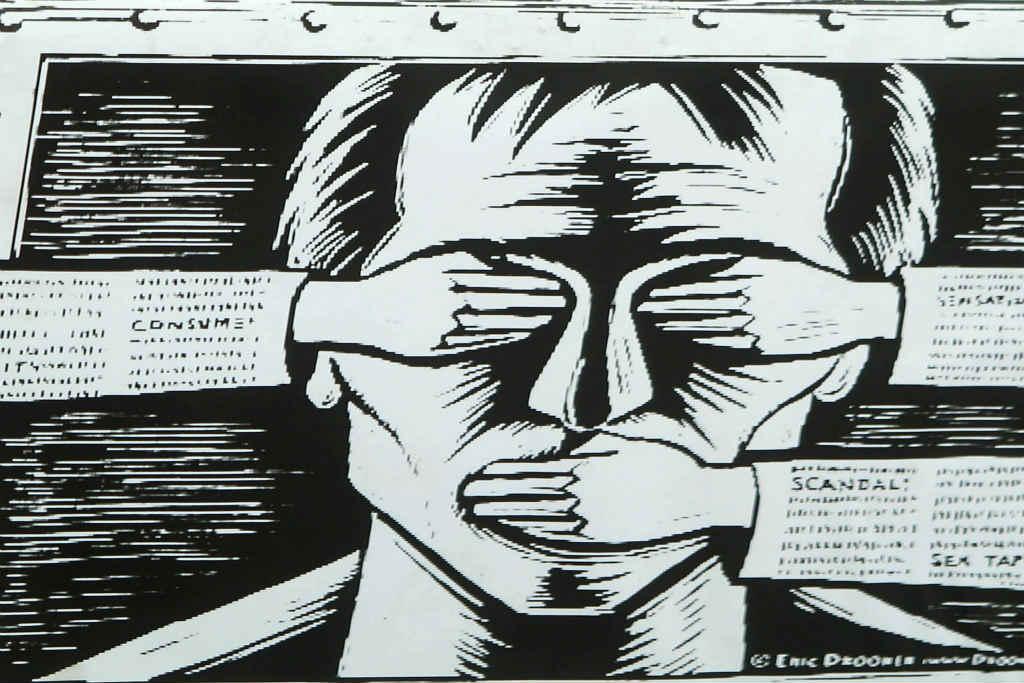

An activist supporting the group Anonymous holds a poster protesting the Indian Government’s increasingly restrictive regulation of the internet.

NEW DELHI, India — Is China right about the internet? The government of India seems to think so.

This week, New Delhi cracked down on social networking sites and blocked mobile phone users from sending text messages, Beijing-style. The controversial move originated as a bid to stop web-based rumor-mongering and hate speech that caused as many as 30,000 people, panicked by the threat of ethnic violence, to flee India's major cities.

But with one draconian internet law already implemented in April, and a knee-jerk Telecom Security Policy swiftly being drafted, the effort threatens to morph into a full-on assault on this country's cherished freedom of speech.

“While I agree that the government must have the right to intervene when things on social media and on SMS are inciteful, hateful, inflammatory or in areas like pornography, the problem is the exercise of that right is being done today in a very, very ad hoc manner, without any oversight,” said Rajeev Chandrasekhar, an independent member of parliament who has criticized the government's efforts to police the web.

“What is happening today can be interpreted as using the opportunity to fix a lot of things that the government doesn't like.”

On Aug. 11, troublemakers spread doctored images from Myanmar and elsewhere to encourage Indian Muslims to attack ethnically distinct Indians from the country's northeast — sparking a riot in Mumbai in which two people were killed and more than 50 injured. And subsequently, the irresponsible or ill-intentioned disseminated false reports of more violence against northeasterners to cause mass panic in Bangalore, Chennai, Pune and other major Indian cities over recent weeks.

On Wednesday, the Indian government asked social media sites including Facebook and Twitter to remove what it deemed inflammatory content. It issued a statement that it had already blocked nearly 250 websites that allegedly included videos and images that could spur violence between communities, and claimed that much of the material originated on sites based in Pakistan.

But critics claim that the control measures did not stop there.

Though the government maintains that it only asked Google, Twitter and Facebook to block links to the websites hosting inflammatory content, not individual user accounts, Twitter users allege that the authorities have sought to block 16 Twitter handles (or nicknamed accounts). The handles in question allegedly include several that resemble the official account of the prime minister's office, including obvious parody accounts, as well as the handles of at least two journalists and right-wing opponents of the ruling Congress Party, such as Pravin Togadia of the far right Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), according to local reports.

“The Prime Minister's Office had requested Twitter to take appropriate action against six persons impersonating the PMO,” the PMO said in a statement issued Friday. “When they did not reply for a long time the Government Cyber Security Cell was requested to initiate action. Twitter has now conveyed to us that action has been taken stating 'we have removed the reported profiles from circulation due to violation of our Terms of Service regarding impersonation.'”

Others say the government's actions went further.

The Economic Times, for instance, posted a series of letters from the Ministry of Communications & IT Department of Telecommunications to all internet service licensees that called for them to block access not only to Togadia's handle and various Facebook pages, but also Twitter handles like @PM0India and the accounts of right-leaning journalist Kanchan Gupta and numerous other right-wing bloggers and commentators. NDTV and Gupta himself also possess copies of the letters.

“I don't think that the government has been particularly happy with the fact that somebody who [does not] endorse this government's policies, its performance, and the manner in which this government has carried out its constitutional responsibilities [has gained an internet following], and they were just looking for an opportunity to sort of try and shut my voice down,” said Gupta in an interview with NDTV.

“Some ISPs did try to block me,” Gupta said. “In some cities, access was blocked, and that is how I got to know of it. People started sending me messages that my handle had been blocked.”

Togadia, who has repeatedly come under fire for speeches like one last year, in which he reportedly called for a revision to the constitution to allow “anyone who converts Hindus to be beheaded,” was still tweeting hours after he claimed the government was out to block him — though his account shows no new tweets since 3 p.m. Thursday. Kanchan Gupta, still going strong on the Delhi area Tata WiMax ISP, tweeted to followers thanking them for their support in the face of attempted censorship on Friday. And many of the other blacklisted accounts also still appeared to be active, at least on that service provider.

“We are only taking strict action against those accounts or people which are causing damage or spreading rumors,” said a statement issued by the home ministry on Friday. “We are not taking action against other accounts, be it on Facebook, Twitter or even SMSes. There is no censorship at all.”

But there is nevertheless some convincing evidence that lawmakers in New Delhi may be starting to believe, like their counterparts in Beijing, that “the mass of information flowing through the internet still presents a challenge to governance,” as an editorial in China's Global Times asserted on Thursday.

More from GlobalPost: For India's censorship bid, it's especially bad timing

Shifting sands of regulation

Already, controversial new rules for the internet implemented in April allow anyone to demand that internet sites and service providers remove supposedly objectionable content based on a sweeping list of criteria. And this week, legislators proposed a new Telecom Security Policy that would force overseas enterprises, including content providers, to allow the government a so-called “master switch” to turn off the internet in times of crisis, the Financial Express cited a draft note for the Cabinet Committee on Security as saying.

Both provisions have serious flaws, according to critics like Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Bangalore-based Centre for Internet and Society. The IT rules notified in April, for example, allow the government to censor speech without informing the public or the person in question of its action. There is no way for someone who is censored to appeal or question the blocking of content and no protocol for the reinstatement of censored speech. And there is no penalty for abusing the law to block speech that is not dangerous.

“Exceptional circumstances such as these, when censorship is legitimate, cannot be used to defend censorship of the internet that is not legitimate, when only the egos of politicians and bureaucrats and public personalities are at stake,” Abraham said.

“This time public order was disrupted and there was serious harm caused by speech. But this occasion cannot be used in retrospect to justify attempts to censor the internet previously that were not legitimate. This occasion cannot be used to justify draconian internet regulation.”

Inflammatory statements like Togadia's call for proselytizers to be beheaded no doubt played some role in encouraging members of the VHP's youth wing, the Bajrang Dal, to burn Australian missionary Graham Staines and his two young sons to death in 1999. And rumors and false or inflammatory media reports about the burning of a train compartment carrying Hindu pilgrims in the city of Godhra played an important role in spurring the Gujarat riots of 2002 to a deadly pitch, all without the aid of the internet.

But there are already clear guidelines for how both problems should be handled. And there is plenty of clear evidence that the willingness of political parties to encourage and exploit the tensions among different ethnic and religious groups — not rumors or hate speech in itself — is the root cause of the country's most serious riots.

Academics like Ashutosh Varshney and Steven I Wilkinson have argued convincingly that India's riots are rarely, if ever, the spontaneous eruptions of rage they may appear to be from outside. Rather, “parties that represent elites within ethnic groups” use anti-minority protests, demonstrations and physical attacks that precipitate riots in order to “encourage members of their wider ethnic category to identify with their party and the ‘majority’ identity to rather than a party that is identified with economic redistribution or some ideological agenda,” as Wilkinson once put it in an essay for The Economic and Political Weekly.

“[The authorities] have soft pedaled a lot of these issues,” said Geeta Sethu, consulting editor at TheHoot.org, an Indian media watchdog. “We have political leaders who go out onto the streets and give speeches which are inflammatory, and they're not picked up immediately. There is absolutely no action taken against them.”

Varshney's and Wilkinson's research related more directly to activities of Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) politicians and associated groups during the Gujarat riots of 2002. But the same argument can be made about the political parties that stirred the pot before July's anti-Muslim violence in Assam, the organizations that mobilized Muslims against northeasterners in Mumbai this month, or the ruling Congress Party itself — which encouraged a pogrom against Sikhs in New Delhi following Indira Gandhi's assassination in 1984.

Hate speech calls out for government intervention, not when it is published on Facebook or sent out by text message, but when there is clear reason to worry that it threatens to spark actual violence — whether because it specifically exhorts people to take up arms, or because, as in the current climate, tensions are already dangerously high.

Similarly, spreading falsehoods does not merit a suspension of freedom of speech unless — as applies, again, to some of the recent text messages and doctored web images — there is a genuine risk that those falsehoods will cause real harm. That's why it's illegal to shout out “bomb” in a crowded movie theater, and shouting out “acting, Boss, acting!” in admiration of Shah Rukh Khan's scenery chewing is merely annoying.

Rioting and violence, on the other hand, is always against the law. The reason for India's troubles is that — unlike when they are confronted by offensive, inflammatory, and, maybe, merely politically aggravating speech on the internet — the authorities too often protect the perpetrators instead of prosecuting them.

More from GlobalPost: India: Social media sites pressed to remove "inflammatory content"

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?