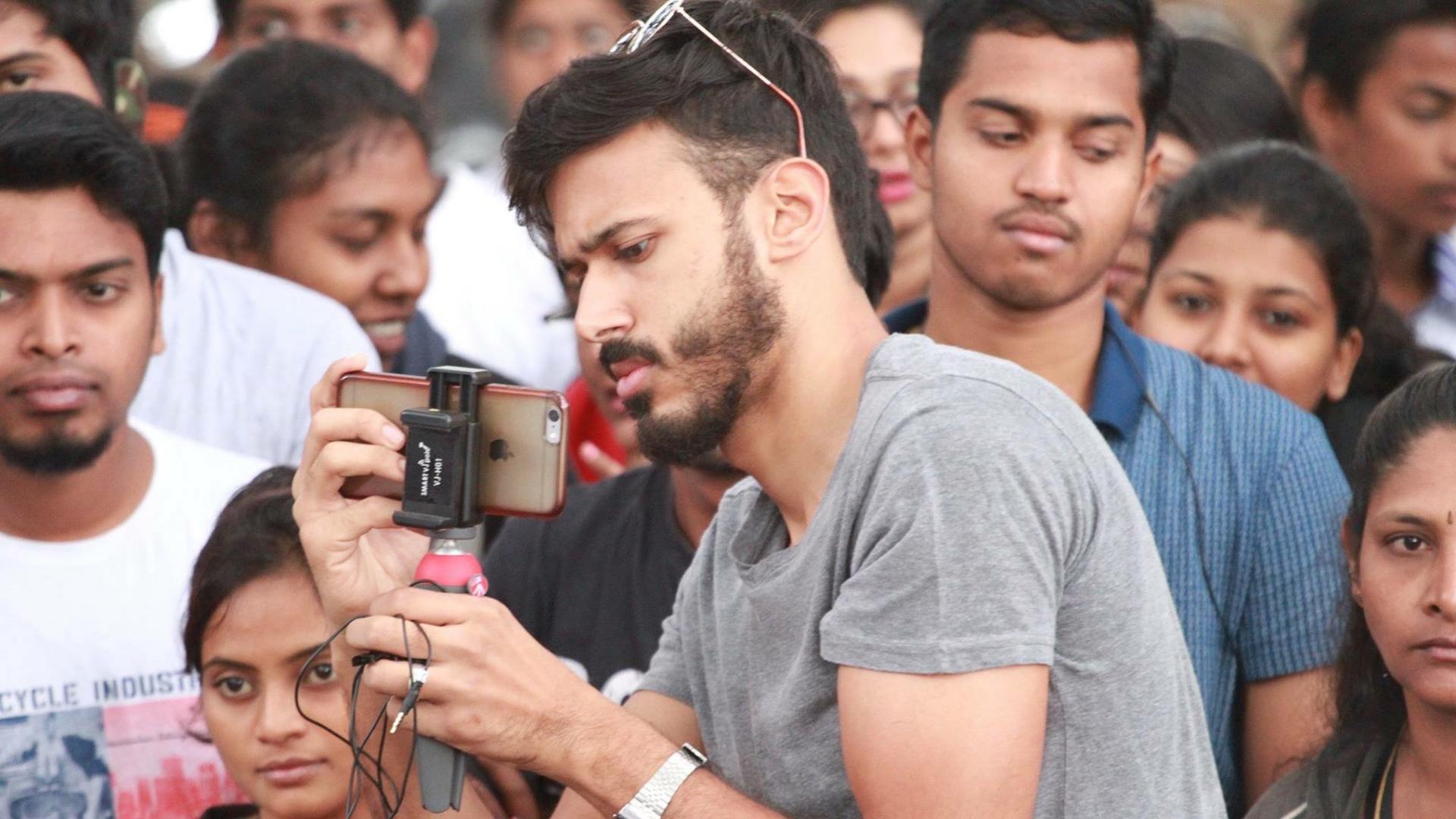

Yusuf Omar, mobile editor of the Hindustan Times, is using Snapchat to give sexual abuse survivors a voice.

Snapchat’s line of face-altering filters have undoubtedly sparked a selfie revolution. However, one journalist is using the app for something more: He’s enabling sexual abuse survivors to share their stories.

Yusuf Omar, mobile editor for the Hindustan Times, used Snapchat technology while covering India’s Climb Against Sexual Abuse earlier this month in Mysore.

“Here in India it’s actually illegal to identify someone who’s been sexually abused in a photograph or a video," Omar says. "So I needed to come up with a way to tell their stories without showing them.”

The answer? Snapchat filters.

Passing his phone to participants of the climb, survivors were able to choose the filter they felt most comfortable with. From dogs to dragons, Snapchat users have several options to mask their identities.

“I think they definitely did open up in a way that I could have never achieved if we had a big broadcast camera with a boom mic and lights in your face,” Omar says. “You’re trying to get somebody to tell the most intimate, personal, and probably a story they never want to have to remember or recount.”

Unlike the usual anonymity tactics, these women were able to tell their stories in the palm of their own hand.

“They had control, and they also gained an element of trust in me,” he says. “First hand, they got to experience what they would be represented as.”

This is an empowering first for many survivors, especially in India, where speaking about sexual assault is highly stigmatized.

Despite Snapchat’s fleeting qualities, Omar says posting to the app can actually reach more people than other social media platforms. While content often gets buried in Facebook and Twitter feeds, posting to a Snapchat story continues to push material to the tops of users’ feeds.

Being a chat app, users were also able to respond to survivors stories directly.

These voices have since gone viral.

While hacking is a serious concern, according to Omar, no one has been able to remove the masks from survivor’s faces. He hopes that remains the case.

“Ideally, I would love to be able to control those masks,” he says. “I would love to be able to tell the sexual abuse survivor that they can design their own filter to cover their faces.”

But until that day, Omar’s using what he has — and it's working.