Wildlife in Chernobyl is thriving 30 years after the nuclear accident

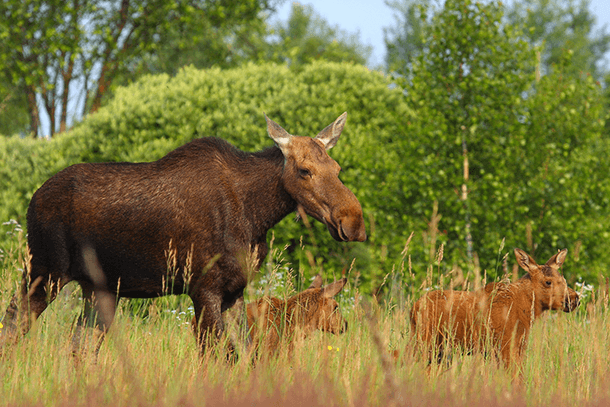

A family of moose who have made the Exclusion Zone their home

Is it possible that radiation isn’t as bad as we think it is — at least for insects and animals?

James Smith, professor of environmental science at Portsmouth University in the UK, has been documenting the effects of radiation on the non-human population around Chernobyl and finds that most species are doing remarkably well.

Smith first went to the area in 1994 to study the transfer of radioactivity in aquatic ecosystems — in lakes and rivers around the zone and around the power station. “We were looking at how the radioactivity got into the rivers and lakes, how long it was going to be there, and how it got taken up by the aquatic food chains,” Smith says.

Smith did a study with biologist colleagues to examine the communities of invertebrates — small insects that live in the sediments of these lakes — to see how they were faring after the big radioactive release. The team studied eight lakes with different levels of contamination. They ranged from lakes with near-natural background radiation levels to Lake Glubokoye, which is the most contaminated lake at Chernobyl.

The scientists found no difference in the aquatic insects in the different lakes. In fact, Smith says, Glubokoye had the highest diversity and abundance of aquatic insects, though it wasn't a statistically significant difference.

Smith has also looked at mammals in the Exclusion Zone, an area of about 4,000 square kilometers, roughly half in Ukraine and half in Belarus. Smith worked with Belarusian colleagues who studied their half of the exclusion zone and both teams found that the mammal communities are doing well.

“The Belarusians have used helicopters to survey the zone for wild boar, roe deer and elk,” Smith says. “They found an increase in population from about one to two years after the accident up to 10 years after the accident.”

Despite the health of the animal population, Smith believes radiation levels remain too high for most people to feel comfortable living there. “Most levels of radiation, even if they're very high at Cherynobyl at the moment, are quite a small risk. But it's a risk that humans often don't choose to take,” Smith explains. “The exclusion zone is uninhabited because we consider the risk of say, one in a 1,000, of getting cancer in human life is not a risk that it's fair for a person to have. But, for a mammal population — a population of wolves or a wild boar — this relatively small risk doesn't affect the population, although on rare occasions it might affect an individual.”

While the region saw a large increase in thyroid cancer after the accident, particularly in Belarus, Smith says it's hard to prove a direct cause and effect. He believes the spike in thyroid cancer occurred primarily because the Soviet Union did not take adequate precautionary measures to stop people from drinking contaminated milk and eating contaminated produce.

“People are always understandably interested in what the human consequences have been,” Smith says. “But statistically, it's going to be very difficult to see that, because we can't distinguish between a cancer that has come from radiation and a cancer that has come from other causes.”

We'll probably never know for sure how many people have died from radiation exposure in Chernobyl, Smith adds, though estimates have been in the range of 8,000 people. “It’s very difficult to discern the small increase in the risk of cancer from Chernobyl in amongst the ‘natural’ cancers,” Smith says.

Several weeks ago, the Ukrainian government declared the exclusion zone a nature reserve. From a human perspective, this makes a lot of sense, Smith says, because it’s very unlikely people will ever want to live in the area again. The animal population, however, has no such qualms and the research now demonstrates no need for concern.

“You could say that radiation is perhaps not bad as we think,” Smith says. “I've been studying radiation for 25 years and thinking and talking to people about it, and thinking about how we perceive it. It’s something that we are naturally frightened of because we tend to associate it with the horrible nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and awful events like Chernobyl and the Fukushima accident. We can't see it, we can't smell it — it kind of has all the elements of things that make us afraid. [But] I think perhaps we're more afraid than we should be. Yes, it's dangerous, but it’s perhaps not as dangerous as we think it is.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!