US methane emissions are drastically underestimated, a new study shows

Leaks from oil and natural gas wells are a major source of methane emissions.

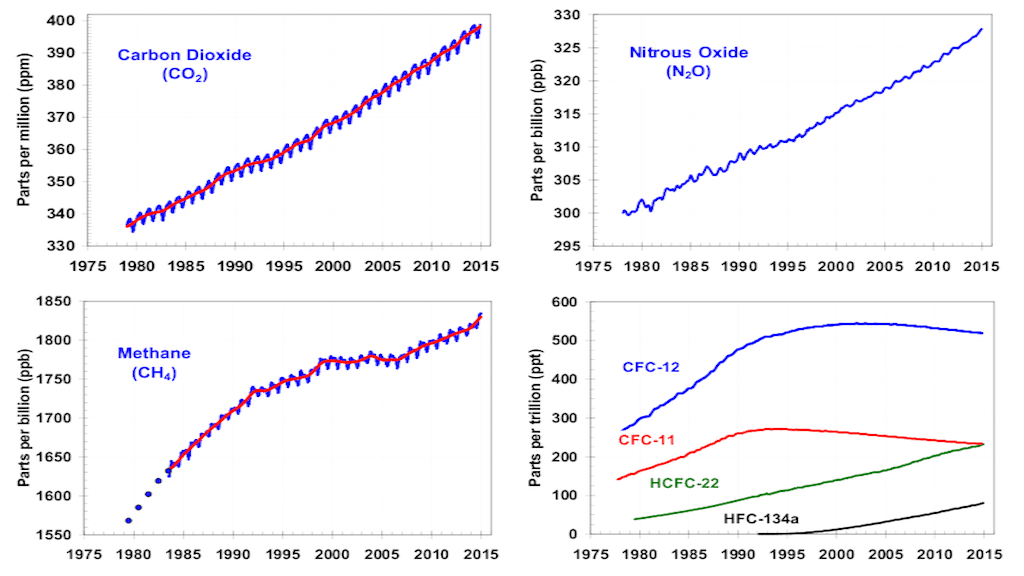

A recent study from Harvard University, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, documents a spike in US methane emissions to levels far higher than previous estimates.

The Harvard team combined satellite data with ground observations and concluded that the US Environmental Protection Agency has been underestimating US methane emissions for at least the past decade.

“[This data] doesn’t come just from us. There are numerous studies showing this,” says the study’s lead author, Daniel Jacob, Harvard professor of atmospheric chemistry and environmental engineering.

“The view is that the methane emissions of the United States are underestimated by 30 to 50 percent,” he says. “And I would say that's pretty much a consensus view from atmospheric scientists that have been looking at methane emissions from the US.”

They examined studies from the past decade that looked at methane levels in the atmosphere over the United States and compared them to EPA emission inventories. These studies repeatedly showed that EPA’s current national emission inventory for methane is too low, Jacobs says.

“We tried to look from the satellite data at ‘fingerprints’ of where methane could be increasing, and we found a large increase over the past decade of emissions of methane in the US — about 30 percent,” Jacob says.

The “tempting hypothesis” is to connect the increase to the shale oil and natural gas boom in the US, Jacob says, but the data “doesn’t provide a smoking gun for figuring out where the methane is coming from. It's just showing that there's been a large increase in methane emissions in the United States.”

EPA doesn’t measure atmospheric levels of methane in its inventory. Instead it uses what Jacob calls a “bottom-up” approach. It gathers information on all the sources it believes are emitting methane and tries to estimate how much methane is associated with each source.

EPA is very good at this, Jacobs says. “It knows where all the landfills are, where all the major livestock operations are, the different components of oil and gas supply system, the leakage from coal mines and so on.”

By contrast, atmospheric scientists use what they call “top-down constraints,” Jacob explains. “The atmosphere tells us how much methane there is and it gives us a rough idea of where it's coming from — but it cannot as easily pinpoint the methane to individual sources.”

Jacob advocates a partnership between the EPA and atmospheric scientists to resolve the differences they are presently seeing. “The atmosphere doesn't lie,” Jacob points out. “When we see methane in the atmosphere, we know it came out of something.”

In terms of getting an accurate figure for global methane emissions, satellite monitoring is a “silver bullet,” Jacob says — and it’s about to get better.

“We've been hampered until now, because the satellite observations that we have are fairly sparse,” he explains. “In other words, from a satellite we can see globally where methane is coming from, but the picture is a little blurry. … But later this year, in October, the Dutch are going to be launching a new satellite instrument and that's going to provide us with a much finer picture of methane emissions.”

“We'll be able to observe methane every day around the world with a resolution of about five miles,” Jacob says. “This is going to revolutionize our ability to observe methane from space.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood