Researchers show wolves use ‘howling dialects’ to communicate

Different canid populations and subspecies use howling as a means of communication and each group has its own preference for use of vocalizations. Researchers found that these vocal preferences fit into one of 21 “dialects.”

A team of Cambridge University researchers has shown that various wolf species and subspecies howl using clearly identifiable “dialects."

People can easily detect differences in wolf howls by ear, but these researchers wanted to measure more precisely how and why the howls of some members of the canid species differ from others, says the study’s lead author, Arik Kershenbaum.

“We don't know whether the cues that we are picking up on as humans are the same cues that are being detected and interpreted by the animals themselves,” Kershenbaum explains. “So we set out to measure similarity and difference quantitively and objectively, without the interference of our human perception.”

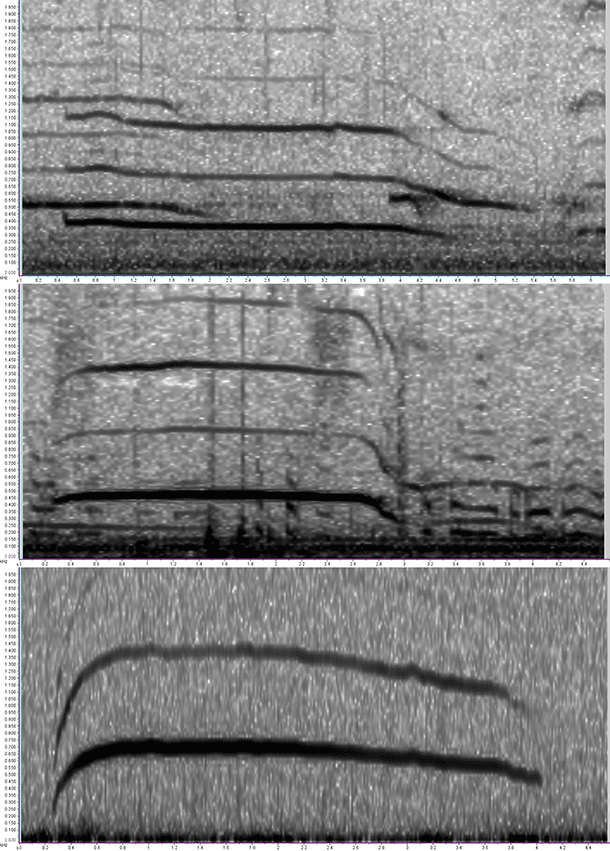

The researchers collected several thousand howls from wolf populations around the world — including different subspecies of gray wolves, red wolves, coyotes, jackals, dingoes and domestic dogs. They assembled the recordings into a database and then put them through mathematical algorithms that extracted the sonic details of each howl and performed comparisons between them.

The computer analysis revealed 21 distinct types of howls, Kershenbaum says, as measured by the variation in the pitch and rhythm of the howl as it progresses — that is, whether the pitch rises, falls or stays constant and whether it occurs in long, sustained tones or short bursts that rapidly fluctuate.

Once they had established the 21 different howl types, the researchers looked at the way these howl types were used by different populations.

“Some species and subspecies would make a lot of use of certain howl types and would neglect others,” Kershenbaum explains. “Some species would make wide use of all of the different howl types and are very varied in their repertoire. And in that sense, the howls represent, if you like, a ‘fingerprint’ for each population, for each subspecies.”

The ability to identify wolves and wolf subspecies by their howl types could help improve management of these animals in the wild, especially in areas where they come into close contact with humans, Kershenbaum says.

“If we can use these kinds of techniques to identify different howls in different behavioral contexts, then we may be able to use the howling to develop techniques for reducing conflict between wild predators and humans, by playing back the appropriate howls,” Kershenbaum explains.

But, he notes, “it would be extremely important to make sure that you play back a howl that says, ‘Don’t come near here, we’re a strong and aggressive pack,’ and not a howl that says, ‘Come over here, we’ve found some interesting food and we’re going to eat it.’”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood