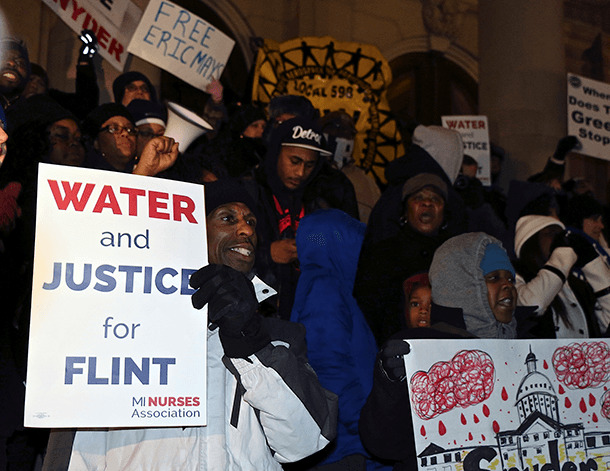

This professor says Flint’s water crisis amounts to environmental racism

Studies show that communities of color are especially vulnerable to environmental injustice and environmental racism.

“Environmental racism is real,” says professor Robert Bullard, considered the father of environmental justice.“It’s so real that even having the facts, having the documentation and having the information has never been enough to provide equal protection for people of color and poor people.”

Bullard is dean of the School of Public Affairs at Texas Southern University and the author of the 1990 book "Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality."

He says lead poisoning in Flint, Mich., and the long delays in addressing it form a classic case of environmental racism. The working class and communities of color, like those in Flint, are far more likely than their white counterparts to be exposed to toxic substances like lead, Bullard says. Recently published studies support his claim.

“Environmental problems, pollution, disasters and health threats often take longer to be acknowledged," Bullard says. "It takes longer for the response and it takes longer for the recovery in communities of color and low-income communities.”

Bullard says “the Flint case fits the example of what's happening with environmental justice across the board."

He compares the response to the water crisis in Flint, a majority-black city, with the response to the ongoing natural gas leak in predominantly white Porter Ranch, Calif., just outside of Los Angeles: State officials in Michigan and regional EPA officials responded to the Flint crisis first with an attempt at a coverup and then defensively — either trying to avoid responsibility or minimizing the extent of the damage. In California, on the other hand, the public utility and state officials have been much more responsive to the concerns of local citizens.

And in Eastern Tennessee, Bullard says he witnessed all levels of government come together to clean up a coal ash spill in Roane County, which is predominantly white. He says local citizens then opposed of disposing waste anywhere in their county or even state.

“Decision-makers… decided to ship the waste 300 miles south to Perry County, Ala., to Uniontown, a predominantly black county and predominantly black city that is very poor,” Bullard says.

“If it's too poisoned for Eastern Tennessee — mostly white — why isn’t the same consideration given to a poor black area?” Bullard asks. “[Y]ou’re taking waste from white areas and shipping it to black areas. We say that is environmental racism.”

Also: Advocate says race is a dominant indicator of pollution — not just in Flint

Now, on top of these local health threats and crises, poor communities and communities of color are going to have to start dealing with climate change, which "is the global environmental justice issue,” Bullard says.

“The communities that have contributed least to global warming and climate change will feel the impacts first, worst and longest. The environmental justice movement and the climate justice movement speak to this issue not just in terms of parts per million and CO2 and greenhouse gases, but also in terms of the equity of climate-change impact.”

The professor thinks real solutions will come about when communities that have historically been left out of environmental decision-making are given a seat at the table.

To help make that happen, Bullard and Dr. Beverly Wright of Dillard University formed the Historically Black College and University Consortium on Climate Change and brought 50 students and some faculty mentors to the Paris climate summit last year.

“What was decided in December in Paris in 2015 will impact these young people going forward,” Bullard says. “So they needed to be in Paris to show that African-Americans are concerned about climate change, we are in solidarity with other people around the world and that the issues that impact people of color and people in the developing world are the same in our own country, as they relate to climate justice.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.