By now, you’ve probably heard the news out of North Dakota.

After many months of protests — and with tensions mounting — the Army Corp of Engineers announced the Dakota Access Pipeline would not, for now at least, be able to pass through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation.

Native American groups and environmental activists have opposed the construction on Native and sacred lands. At the heart of it all: the Missouri River. The massive pipeline was supposed to go through it, but activists feared that it could contaminate the water supply. They began calling themselves the “water protectors.”

A tipping point came a few days ago, when several thousand US military veterans arrived at the camp, saying they would serve as “human shields” in front of the protesters. Most of the veterans were Native. According to a 2010 census, there are more than 150,000 Native veterans.

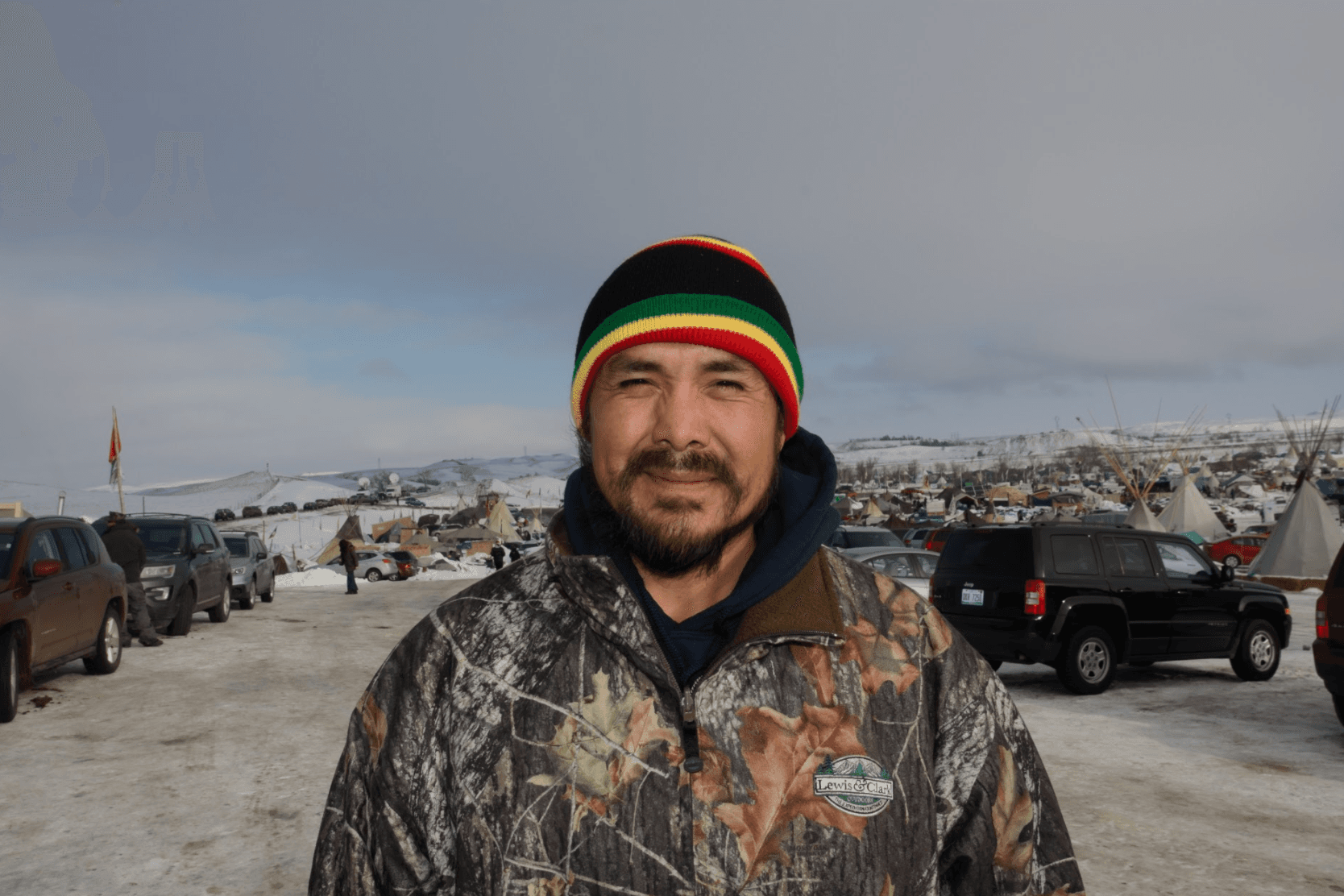

The very first man I met upon arriving at the camp was a Navajo vet, named John Shirley. “I’m here to be, basically, a human shield,” he explained.

Shirley is a veteran of the first Iraq War. He came from Arizona to guard the protesters. I met him at the entrance to the sprawling camp, where, in recent weeks, protesters have clashed with National Guard soldiers and local police. And that’s when veterans like Shirley decided to come help people. To be that human shield.

To “stand there, close my eyes, and take whatever comes at me. As long as I can block and deflect whatever it may be … you know, that’s the way we was trained,” he says.

Like many veterans, he felt outraged at the way protesters were being treated by police. And he was also frustrated that Native lands and resources could be endangered by the pipeline. “I never thought I would be doing this on American soil,” he says. “Protecting the American people from their own government. I never thought that would happen, you know?”

Several thousand veterans felt the same way, pouring into the camp over the weekend. At a meeting Saturday night, in a warehouse outside Standing Rock, veterans were instructed to be nonviolent. Sage burned while men and women in uniform received marching orders: “We will not instigate.” They were told to spread the orders among themselves. No direct confrontation, and nothing that could harm the cause.

At that warehouse, there was a sense the pipeline was inevitable. By the next afternoon, they found out that wasn’t the case.

At the camp, Brandi King, a Nakota veteran of Iraq, said nonviolence is a challenging order for a warrior. “Fighting for peace is a lot harder than — I mean anyone can pull a trigger. … Actually being peaceful, and fighting for that — that takes a warrior. It takes a strong person to be peaceful.”

“That’s all I grew to know. Learning how to fight.”

She returned from Iraq with severe PTSD. “I wanted to take my life. I tried to take my life.”

She came home to a system that wasn’t prepared to cope with women vets like her.

“They weren’t prepared for the amount of women who were combat veterans, who were going to be coming in with wounds and with PTSD.”

King said after 10 years of not knowing what to do with herself, she finally began to heal at Standing Rock. “This — seeing people together, seeing people support each other, that provides healing for me. Seeing my indigenous brothers and sisters being able to stand up with pride, provides a healing for me.”

But it still wasn’t an easy decision, to come, knowing she might have to face off with soldiers on the other side of this fight. At the end of the day, she figured, “if I was willing to die for this government, I was willing to die for this country. I was willing to die for every single person here … then give me some peace. Allow me to live for my ancestors. Allow me to create a better path for the ones who are coming. For my nieces and nephews, for the unborn. Let me be a part of that.”

She prayed on it. That prayer was answered Sunday afternoon. The air was absolutely frigid, and under a crisp blue sky, the announcement came: The Army Corps of Engineers, for now, would not give permission for the pipeline to go under the Missouri River.

Shortly after hearing the news, I went to find King. She was right outside her teepee, away from the crowd.

“You pray to experience this, but when it actually happens — I don’t know. I can’t come up with the words right now,” she said, amidst tears of joy. “There wasn’t any violence. There wasn’t any weapons. To feel that spiritual reinforcement— from all of those who fought in Vietnam, Desert Storm, Iraq, Afghanistan. All of those that brought everything that they had, everything that they took to every battle. Every battleground. But this was the spiritual battleground.”

The crowd around her roared and erupted in song. King, meanwhile, was speechless.