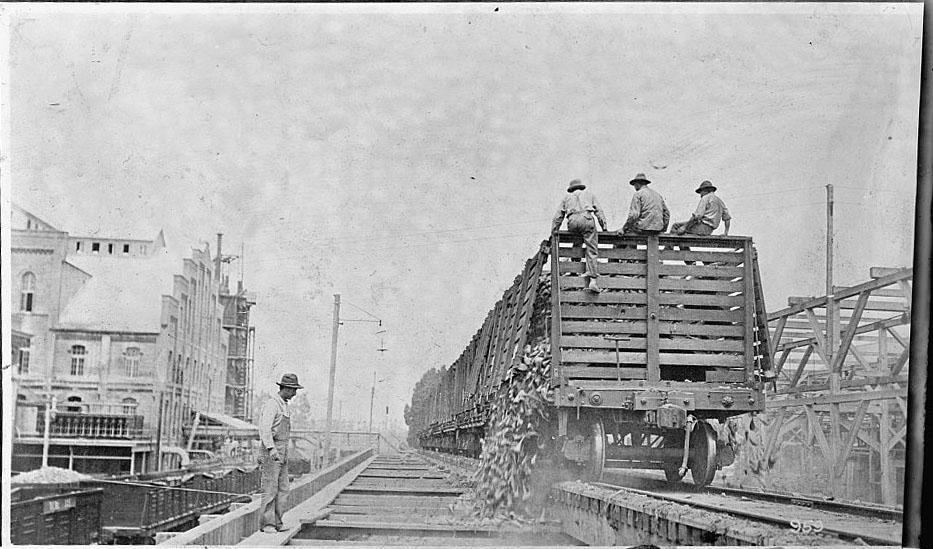

Japanese migrant strawberry pickers, possibly on Vashon Island, Washington, February 14, 1915.

Berry season is waning, but the harvest hasn't always been so sweet for the migrant workers who pick the fruit in fields across the United States. A conflict between Mexican migrant workers and the Japanese American family-owned Sakuma Brothers berry farm in Washington state shows just how thorny the harvest can be.

But conflicts over wages and worker rights are not unique to this time and place, or even to the berry harvest. Along with other migrant groups, workers of Japanese and Mexican heritage have been central to the story of modern American agriculture. And as field workers, farmers, tenants, strikers and scabs, their stories have intersected at many points along the way.

The last century saw several of these cross-cultural encounters: In 1933, the El Monte berry strike pitted mostly Japanese American growers and field managers against predominantly Mexican American laborers in a conflict over wages in California’s berry industry. In the 1940s, Mexican braceros filled jobs left behind when Japanese Americans were incarcerated at the height of the 1942 spring harvest. In the 1970s, the Nisei Farmers League undermined strikes organized by Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers union by bringing in outside workers to cross the picket lines.

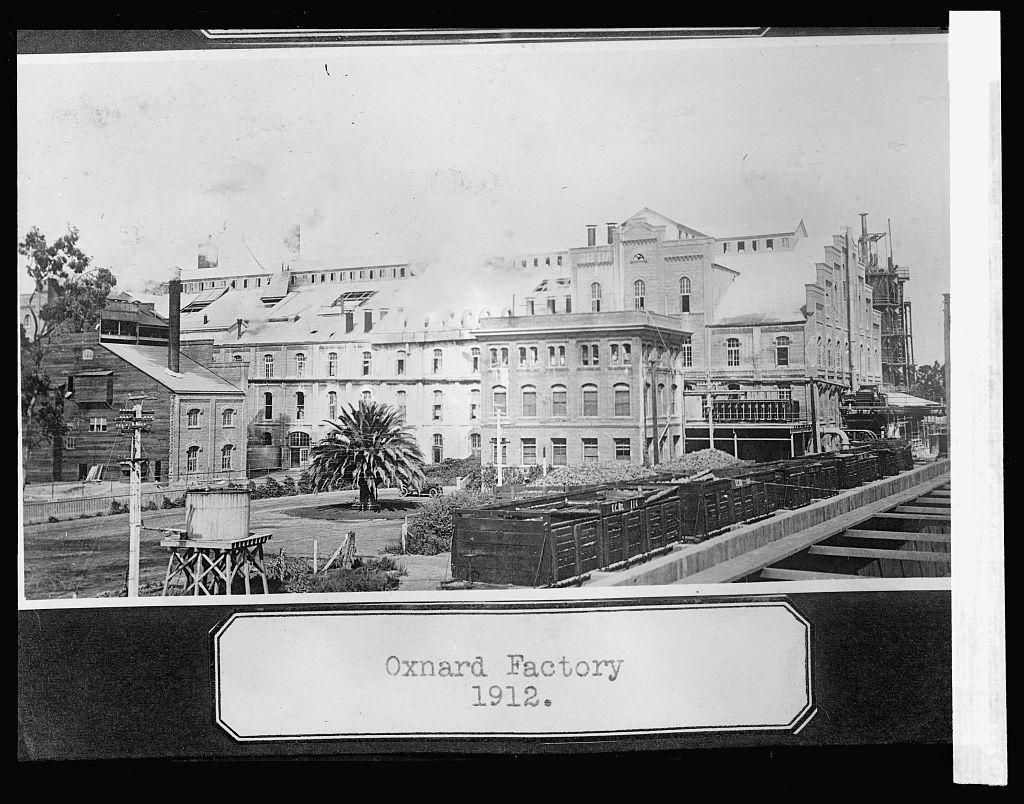

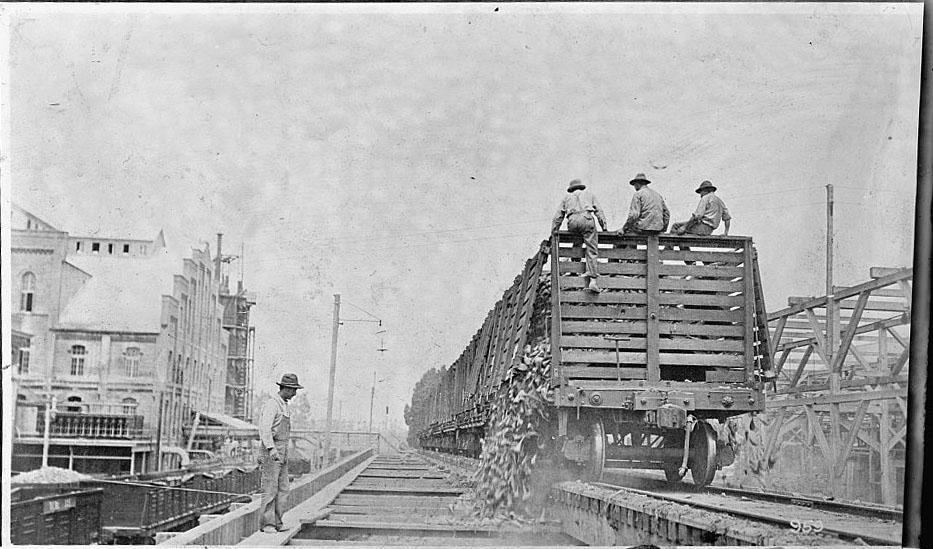

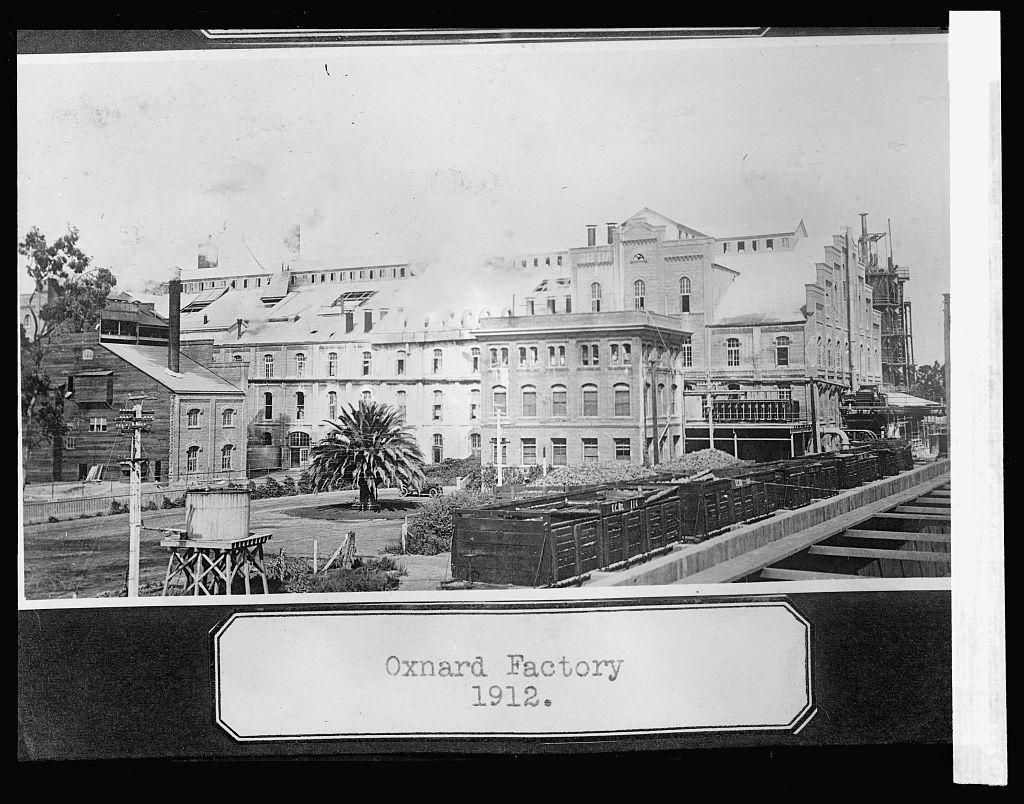

While the two groups were on opposing sides in many of these encounters, there were also remarkable instances of unity. One example stands out in its demonstration of solidarity. The story brings us back to turn-of-the-century Oxnard, California. The region was experiencing a major agricultural boom, owing to the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad and a newly completed network of irrigation channels. Workers came from Mexico, Japan, India, China (yes, some Chinese workers remained despite the not subtle efforts to eradicate them), the Philippines, and even Riverside’s Indian boarding school, the Sherman Institute. This multilingual, multinational and easily replenishable workforce allowed businessmen and farm owners to keep wages low and their workers disenfranchised.

But that wasn’t always the case. The close proximity and shared experience of the diverse workforce also “promoted the creation of unexpected, and often intricate, cross-cultural relationships,” Frank P. Barajas writes in his book, Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard, California, 1898-1961.

But when the company hired an outside contractor that sought to reduce wages and force workers to be paid in credit at overpriced company stores rather than in cash, workers rallied in opposition.

Around 200 Mexican betabeleros (beet pickers) and 1,000 Japanese buranke katsugi (blanket carriers, so named for their itinerant lifestyles) united. They formed the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA), one of America’s first multiracial labor unions. Communicating through interpreters, this multilingual group successfully negotiated a strategy for action. On February 11, 1903, workers walked off the job in what would become the “first successful agricultural strike” in Southern California, according to the Encyclopedia of U. Labor and Working-Class History. By the end of March, the group’s numbers had grown to 1,300 and frustrated growers brought in scabs to cross the picket lines.

As tensions mounted, the conflict turned violent. On March 23, 1903 members of the JMLA were attacked by a local anti-union farmer. One man, Louis Vasquez, was killed and four others wounded. The murderous farmer was tried but found not guilty, leading the JMLA to take a militant turn.

Shortly after the attack, the JMLA issued the following statement:

“Our union has always been law abiding, and has in its ranks at least nine-tenths of all the beet thinners in this section — who have not asked for a raise in wages, but only that the wages be not lowered, as was demanded by the beet growers. Many of us have families, were born in this country, and are lawfully seeking to protect the only property that we have — our labor. It is just as necessary for the welfare of the valley that we get a decent living wage, as it is that the machines in the great sugar factory be properly oiled — if the machines stop, the wealth of the valley stops, and likewise if the laborers are not given decent wage, they too, must stop work, and the whole people of the country will stop with them.”

The movement grew in size and visibility and the American Beet Sugar Company eventually caved to their demands, agreeing to return to the original wage scale. But as the JMLA sought to transform itself into the chartered Sugar Beet Farm Laborers Union, they received an unexpected blow from an organization that ought to have been an ally. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) — the body that governed labor unions — issued a charter to formally recognize the union. However, they delivered with it an unexpected caveat: AFL President Samuel Gompers granted workers of Mexican heritage “all rights and privileges” in the union, but mandated that they would “under no circumstance accept membership of any Chinese or Japanese.”

Despite the AFL’s principles that “race, color, religion or nationality, shall be no bar to fellowship in the American Federation of Labor,” Gompers had succumbed to anti-Asian sentiment. But the Mexican American members of the JMLA refused to take this racist, partial victory. In response to Gompers, the union sent the unsigned charter back and stood by their Japanese American brothers. In a letter that accompanied the rejected charter, the union’s secretary, J.M. Lizarraras, wrote:

“In the past we have counseled, fought and lived on very short rations with our Japanese brothers, and toiled with them in the fields, and they have been uniformly kind and considerate. We would be false to them and to ourselves and to the cause of Unionism if we, now, accepted privileges for ourselves which are not accorded to them. We are going to stand by men who stood by us in the long, hard fight which ended in a victory over the enemy. We therefore respectfully petition the A. F. of L. to grant us a charter under which we can unite all the Sugar Beet & Field Laborers of Oxnard, without regard to their color or race. We will refuse any other kind of charter, except one which will wipe out race prejudices and recognize our fellow workers as being as good as ourselves.”

The AFL stood its ground and refused to grant a charter to the union. That, combined with a revision to the labor contractor system in Oxnard, led to the quick dissolution of the new sugar beer union. The organization had a short life, but this union of Japanese and Mexican American workers stands as a powerful example of interracial solidarity in a history of labor relations that would, more often than not, turn sour as power dynamics shifted.

Over the next several decades, Japanese Americans were able to pool resources and form partnerships that helped them leverage their social positions relative to other migrant groups. Strategically working around the alien land laws that prevented them from owning farm land, Japanese Americans slowly began expanding their agricultural holdings. The unjust and illegal incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II disrupted this trajectory, but by the late 1940s the alien land laws had been rendered unenforceable and many Japanese Americans were again on the path to prosperity.

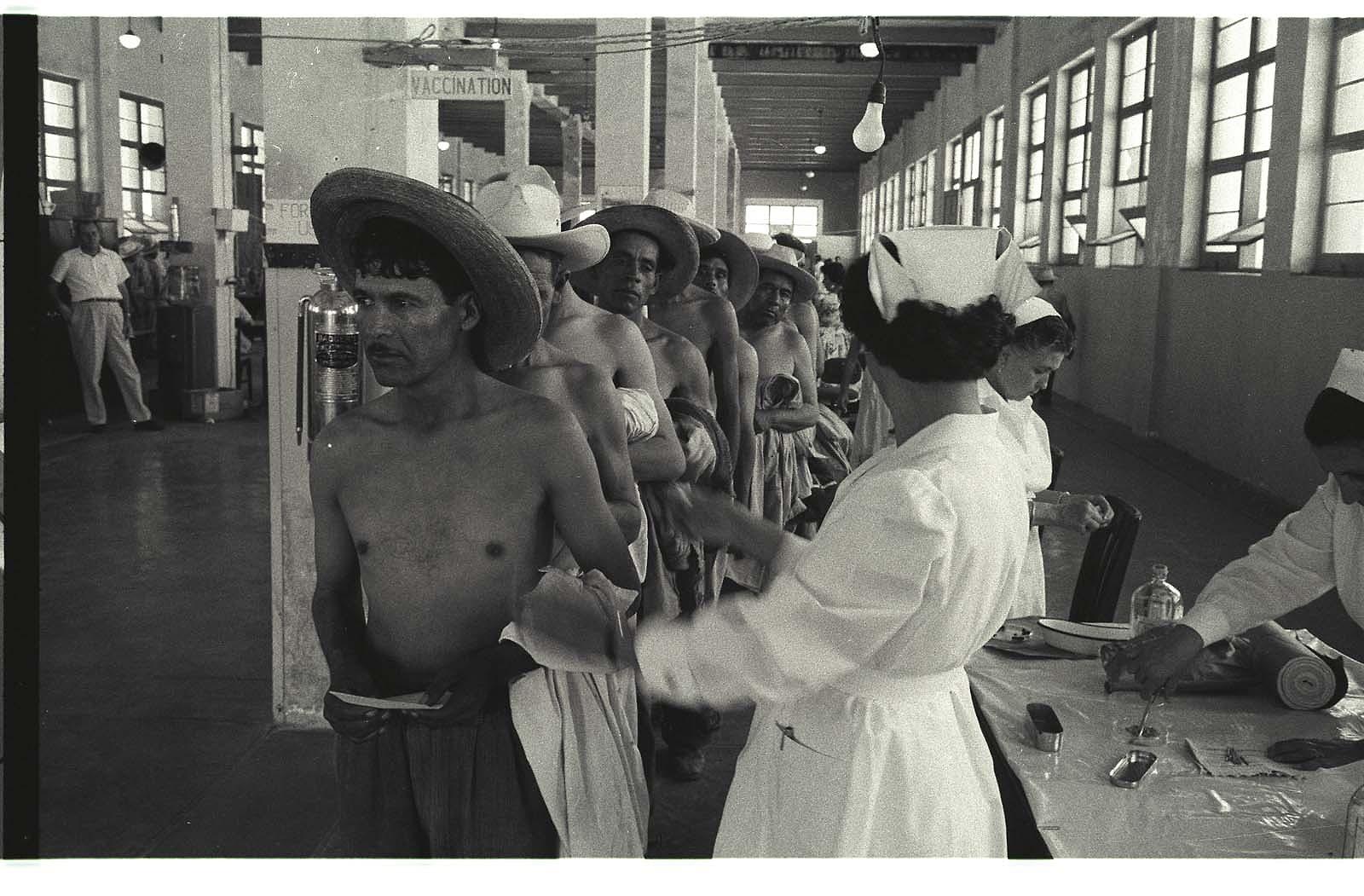

Meanwhile, millions of temporary workers from Mexico continued to come North through the Bracero Program, the US’s largest agricultural contract labor program which some have likened to “legalized slavery.” Though Braceros worked strenuous jobs for a pittance, suffered countless abuses, and were provided with sub-standard accommodations, many criticized them and other undocumented workers from Mexico for taking jobs from domestic workers and depressing wages. Soon, these exploited Mexican laborers were scorned just as Asian workers had been earlier in the century.

Grassroots activism in opposition to the Bracero Program eventually led to its termination in 1964, and farm workers who remained in the US gradually won union representation and leverage for better working conditions. From this emerged the United Farm Workers, a union and civil rights movement led by Cesar Chavez. While the movement was led by Mexican Americans, the group had wide support from others, including Larry Itliong and other Filipino Americans who comprised another agricultural underclass.

But Japanese and Mexican Americans again found themselves at odds over agricultural and labor issues. These tensions were amplified by socio-economic factors and perceptions of the other group’s intentions. In 1971, Japanese American-owned farms were at the center of UFW protests and strikes. Many farm owners felt they were being unfairly targeted.

“It was widely believed … that the United Farm Workers felt (either at the local or higher levels) that the Japanese would be easy organizing targets because of their general lack of resistance to being relocated to concentration camps during World War II,” wrote scholar Steven Fugita.

In response, the farmers banded together to form the Nisei Farmers League. Their hope was to collectively protect their interests in the face of UFW actions and to defend their reputations as Japanese Americans. In a full-page ad published in 20 leading California newspapers, Harry Kubo, the first president of the NFL reminded readers of the historical injustice he had suffered and used it as a justification to stand his ground against the UFW. Alongside a portrait of Kubo, the ad read:

“1942. WWII. Tule Lake Japanese-American detention camp. My family lost everything. I was 20 years old and I gave up my personal rights without a fight. Never again.”

In addition to inter-ethnic conflict, the opposition to the United Farm Workers movement took a toll on Japanese Americans. Disputes between younger generations of Sansei and older generations of Nisei broke out. The rift was felt deeply by the Japanese American Citizens League, where clashes over Sansei support for the UFW and other social justice issues eventually led to Sansei employees resigning from their league positions en masse in 1972.

The radical pan-Asian journal Gidra also protested the actions of their elders in the Nisei Farmers League, encouraging readers to support boycotts of grapes and other products that didn’t bear a union label. And in an interview conducted with Densho years later, Ryo Imamura recalled trying to garner Nisei support for the UFW, “there’s no way that they could feel separate from the Chicano farm laborers” because in recent memory Japanese Americans had themselves occupied the lowest positions in the hierarchy of agricultural labor.

While the divisions between the farmers league and the union were complicated by social, economic, and generational factors, both sides summoned history and cultural identity in waging attacks and articulating defenses. The spirit of unity seen between Japanese and Mexican American farm workers in the Oxnard strike was evident in Sansei solidarity, but nowhere to be found in the exchanges between the two groups most closely involved in the labor dispute.

More: Despite history, Japanese Americans and African Americans are working together to claim their rights

This evolution from comradery to competition is a perfect illustration of the “divide and conquer” mentality that has, by design, come to define modern American agriculture and race relations. Divisions among workers, as well as between farmers and the agricultural labor force, helps keep workers disenfranchised and profits high. Add to this the fact that immigrant groups have historically been incentivized to elevate their own status by standing on the backs of fellow newcomers. Racist constructs like the model minority myth, disparities in wealth and citizenship status, and America’s revolving door of migrant scapegoating have sown further divisions.

But the interracial allegiance in Oxnard in 1903 remains as a powerful example of what can happen when groups unite in solidarity instead of giving into the social forces working to pit them against one another.

Berry season is waning, but the harvest hasn't always been so sweet for the migrant workers who pick the fruit in fields across the United States. A conflict between Mexican migrant workers and the Japanese American family-owned Sakuma Brothers berry farm in Washington state shows just how thorny the harvest can be.

But conflicts over wages and worker rights are not unique to this time and place, or even to the berry harvest. Along with other migrant groups, workers of Japanese and Mexican heritage have been central to the story of modern American agriculture. And as field workers, farmers, tenants, strikers and scabs, their stories have intersected at many points along the way.

The last century saw several of these cross-cultural encounters: In 1933, the El Monte berry strike pitted mostly Japanese American growers and field managers against predominantly Mexican American laborers in a conflict over wages in California’s berry industry. In the 1940s, Mexican braceros filled jobs left behind when Japanese Americans were incarcerated at the height of the 1942 spring harvest. In the 1970s, the Nisei Farmers League undermined strikes organized by Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers union by bringing in outside workers to cross the picket lines.

While the two groups were on opposing sides in many of these encounters, there were also remarkable instances of unity. One example stands out in its demonstration of solidarity. The story brings us back to turn-of-the-century Oxnard, California. The region was experiencing a major agricultural boom, owing to the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad and a newly completed network of irrigation channels. Workers came from Mexico, Japan, India, China (yes, some Chinese workers remained despite the not subtle efforts to eradicate them), the Philippines, and even Riverside’s Indian boarding school, the Sherman Institute. This multilingual, multinational and easily replenishable workforce allowed businessmen and farm owners to keep wages low and their workers disenfranchised.

But that wasn’t always the case. The close proximity and shared experience of the diverse workforce also “promoted the creation of unexpected, and often intricate, cross-cultural relationships,” Frank P. Barajas writes in his book, Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard, California, 1898-1961.

But when the company hired an outside contractor that sought to reduce wages and force workers to be paid in credit at overpriced company stores rather than in cash, workers rallied in opposition.

Around 200 Mexican betabeleros (beet pickers) and 1,000 Japanese buranke katsugi (blanket carriers, so named for their itinerant lifestyles) united. They formed the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA), one of America’s first multiracial labor unions. Communicating through interpreters, this multilingual group successfully negotiated a strategy for action. On February 11, 1903, workers walked off the job in what would become the “first successful agricultural strike” in Southern California, according to the Encyclopedia of U. Labor and Working-Class History. By the end of March, the group’s numbers had grown to 1,300 and frustrated growers brought in scabs to cross the picket lines.

As tensions mounted, the conflict turned violent. On March 23, 1903 members of the JMLA were attacked by a local anti-union farmer. One man, Louis Vasquez, was killed and four others wounded. The murderous farmer was tried but found not guilty, leading the JMLA to take a militant turn.

Shortly after the attack, the JMLA issued the following statement:

“Our union has always been law abiding, and has in its ranks at least nine-tenths of all the beet thinners in this section — who have not asked for a raise in wages, but only that the wages be not lowered, as was demanded by the beet growers. Many of us have families, were born in this country, and are lawfully seeking to protect the only property that we have — our labor. It is just as necessary for the welfare of the valley that we get a decent living wage, as it is that the machines in the great sugar factory be properly oiled — if the machines stop, the wealth of the valley stops, and likewise if the laborers are not given decent wage, they too, must stop work, and the whole people of the country will stop with them.”

The movement grew in size and visibility and the American Beet Sugar Company eventually caved to their demands, agreeing to return to the original wage scale. But as the JMLA sought to transform itself into the chartered Sugar Beet Farm Laborers Union, they received an unexpected blow from an organization that ought to have been an ally. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) — the body that governed labor unions — issued a charter to formally recognize the union. However, they delivered with it an unexpected caveat: AFL President Samuel Gompers granted workers of Mexican heritage “all rights and privileges” in the union, but mandated that they would “under no circumstance accept membership of any Chinese or Japanese.”

Despite the AFL’s principles that “race, color, religion or nationality, shall be no bar to fellowship in the American Federation of Labor,” Gompers had succumbed to anti-Asian sentiment. But the Mexican American members of the JMLA refused to take this racist, partial victory. In response to Gompers, the union sent the unsigned charter back and stood by their Japanese American brothers. In a letter that accompanied the rejected charter, the union’s secretary, J.M. Lizarraras, wrote:

“In the past we have counseled, fought and lived on very short rations with our Japanese brothers, and toiled with them in the fields, and they have been uniformly kind and considerate. We would be false to them and to ourselves and to the cause of Unionism if we, now, accepted privileges for ourselves which are not accorded to them. We are going to stand by men who stood by us in the long, hard fight which ended in a victory over the enemy. We therefore respectfully petition the A. F. of L. to grant us a charter under which we can unite all the Sugar Beet & Field Laborers of Oxnard, without regard to their color or race. We will refuse any other kind of charter, except one which will wipe out race prejudices and recognize our fellow workers as being as good as ourselves.”

The AFL stood its ground and refused to grant a charter to the union. That, combined with a revision to the labor contractor system in Oxnard, led to the quick dissolution of the new sugar beer union. The organization had a short life, but this union of Japanese and Mexican American workers stands as a powerful example of interracial solidarity in a history of labor relations that would, more often than not, turn sour as power dynamics shifted.

Over the next several decades, Japanese Americans were able to pool resources and form partnerships that helped them leverage their social positions relative to other migrant groups. Strategically working around the alien land laws that prevented them from owning farm land, Japanese Americans slowly began expanding their agricultural holdings. The unjust and illegal incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II disrupted this trajectory, but by the late 1940s the alien land laws had been rendered unenforceable and many Japanese Americans were again on the path to prosperity.

Meanwhile, millions of temporary workers from Mexico continued to come North through the Bracero Program, the US’s largest agricultural contract labor program which some have likened to “legalized slavery.” Though Braceros worked strenuous jobs for a pittance, suffered countless abuses, and were provided with sub-standard accommodations, many criticized them and other undocumented workers from Mexico for taking jobs from domestic workers and depressing wages. Soon, these exploited Mexican laborers were scorned just as Asian workers had been earlier in the century.

Grassroots activism in opposition to the Bracero Program eventually led to its termination in 1964, and farm workers who remained in the US gradually won union representation and leverage for better working conditions. From this emerged the United Farm Workers, a union and civil rights movement led by Cesar Chavez. While the movement was led by Mexican Americans, the group had wide support from others, including Larry Itliong and other Filipino Americans who comprised another agricultural underclass.

But Japanese and Mexican Americans again found themselves at odds over agricultural and labor issues. These tensions were amplified by socio-economic factors and perceptions of the other group’s intentions. In 1971, Japanese American-owned farms were at the center of UFW protests and strikes. Many farm owners felt they were being unfairly targeted.

“It was widely believed … that the United Farm Workers felt (either at the local or higher levels) that the Japanese would be easy organizing targets because of their general lack of resistance to being relocated to concentration camps during World War II,” wrote scholar Steven Fugita.

In response, the farmers banded together to form the Nisei Farmers League. Their hope was to collectively protect their interests in the face of UFW actions and to defend their reputations as Japanese Americans. In a full-page ad published in 20 leading California newspapers, Harry Kubo, the first president of the NFL reminded readers of the historical injustice he had suffered and used it as a justification to stand his ground against the UFW. Alongside a portrait of Kubo, the ad read:

“1942. WWII. Tule Lake Japanese-American detention camp. My family lost everything. I was 20 years old and I gave up my personal rights without a fight. Never again.”

In addition to inter-ethnic conflict, the opposition to the United Farm Workers movement took a toll on Japanese Americans. Disputes between younger generations of Sansei and older generations of Nisei broke out. The rift was felt deeply by the Japanese American Citizens League, where clashes over Sansei support for the UFW and other social justice issues eventually led to Sansei employees resigning from their league positions en masse in 1972.

The radical pan-Asian journal Gidra also protested the actions of their elders in the Nisei Farmers League, encouraging readers to support boycotts of grapes and other products that didn’t bear a union label. And in an interview conducted with Densho years later, Ryo Imamura recalled trying to garner Nisei support for the UFW, “there’s no way that they could feel separate from the Chicano farm laborers” because in recent memory Japanese Americans had themselves occupied the lowest positions in the hierarchy of agricultural labor.

While the divisions between the farmers league and the union were complicated by social, economic, and generational factors, both sides summoned history and cultural identity in waging attacks and articulating defenses. The spirit of unity seen between Japanese and Mexican American farm workers in the Oxnard strike was evident in Sansei solidarity, but nowhere to be found in the exchanges between the two groups most closely involved in the labor dispute.

More: Despite history, Japanese Americans and African Americans are working together to claim their rights

This evolution from comradery to competition is a perfect illustration of the “divide and conquer” mentality that has, by design, come to define modern American agriculture and race relations. Divisions among workers, as well as between farmers and the agricultural labor force, helps keep workers disenfranchised and profits high. Add to this the fact that immigrant groups have historically been incentivized to elevate their own status by standing on the backs of fellow newcomers. Racist constructs like the model minority myth, disparities in wealth and citizenship status, and America’s revolving door of migrant scapegoating have sown further divisions.

But the interracial allegiance in Oxnard in 1903 remains as a powerful example of what can happen when groups unite in solidarity instead of giving into the social forces working to pit them against one another.