How a new prime minister will reshape Canada’s environmental policies

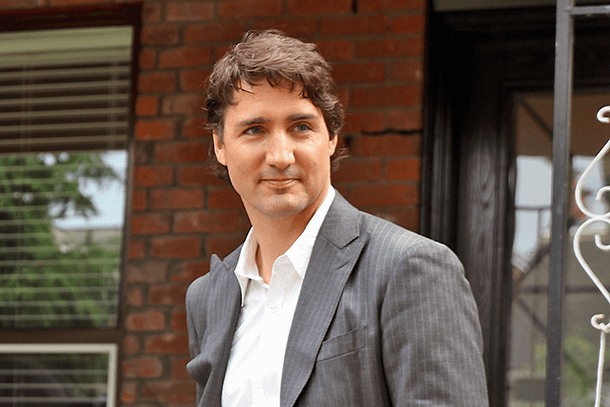

Canada’s newly-elected Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau.

The election of Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau as Canada's prime minister is raising questions about how the country's extraction-based economy can be reconciled with Trudeau’s conservation ethic.

During the campaign, Trudeau and the Liberal Party made promises regarding new spending on green energy and green infrastructure, but the Liberal environmental platform presented no comprehensive plan or concrete targets, says Reuters Investigative Resources correspondent Mike De Souza. Then on Friday, President Barack Obama shelved the centerpiece of Canada's pre-Trudeau economic efforts, the Keystone XL pipeline that would have transported oil from Canada's tar sands throughout the Midwest to America's Gulf Coast.

As prime minister, Stephen Harper, who comes from Alberta, the hub of tar-sands extraction, pushed hard for more pipelines, including the Keystone XL. He also pulled out of the Kyoto Protocol climate treaty, questioned the science of climate change and muzzled environmental scientists, De Souza says.

In contrast, the Liberal Party has concerns about changes Conservatives made to the environmental regulation process in Canada and about environmental laws that were scrapped or rewritten in the past couple of years by the Harper government, De Souza says. During the campaign, they promised to look at fixing the environmental review process.

The Liberal Party has also been critical of Conservative attempts to silence scientists who are sounding the alarm on climate change. About three weeks before election day, Trudeau released an open letter expressing his view that the government should show more respect for public servants.

“He believed the previous government wasn't doing that — and he specifically mentioned the ‘muzzling’ issue,” De Souza says. “He said that if a Liberal government were elected, it would put a stop to these practices; it would allow scientists to speak freely on their work.”

The Liberal Party had supported the Keystone XL project, however, based on its economic benefits and the assumption that there would be efforts to crack down on the greenhouse gas emissions from the oil sands.

But its stance is more nuanced on future energy, according to De Souza. “They say that whatever policies they introduce are designed to ensure that global warming does not exceed two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels,” De Souza explains. “They talked about carbon pricing across economy, but they have said that it's up to the provinces to come up with their own individual plans … based on the unique industries in each province.”

Canada has generally been in the top 10 to 15 countries in the world in terms of emissions per person, but parts of the Canadian economy are becoming more efficient, De Souza says.

The Ontario government shut down coal-fired power plants, which significantly reduced Canada's carbon footprint; the British Columbia government introduced a carbon tax; and the Québec government introduced a modest carbon tax and announced a partnership with California on a cap and trade program they are trying to expand to other partners, including Ontario.

“I would say that Canada's GHGs could be heading in the right direction, but probably not fast enough,” De Souza says. “If they are, it's because of action by provincial governments.”

The province of Alberta remains the biggest problem, De Souza says. It has seen a large increase in emissions in the last decade, but a new, left-leaning government in Alberta has promised to address the issue more than previous governments. It has increased the carbon pricing that was already in place and it looks to introduce a more comprehensive plan within the next year.

“So possibly, we're going to see some movement from Alberta that could have a significant impact on Canada's carbon footprint going forward,” De Souza says.

Whatever Trudeau does will have to be led by the Alberta government, De Souza believes.

“If the Alberta government decides not to do anything, maybe at that point we might see a test of what Mr. Trudeau and his future government are willing to do,” De Souza explains. “But right now, there's still quite a bit of uncertainty about how and if he can tackle this sector.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.