Mike and Linda Gioscia remember how anxious their son Ethan used to be when he was a toddler.

“Just bringing him places he would have these meltdowns,” Mike Gioscia said. “He didn’t know what to expect. It took us a long time to realize this — I was like 'We're just going to Stop and Shop — what are you afraid of? What’s wrong?'"

Doctors diagnosed Ethan with a form of autism — and suddenly Mike and Linda found themselves searching for answers.

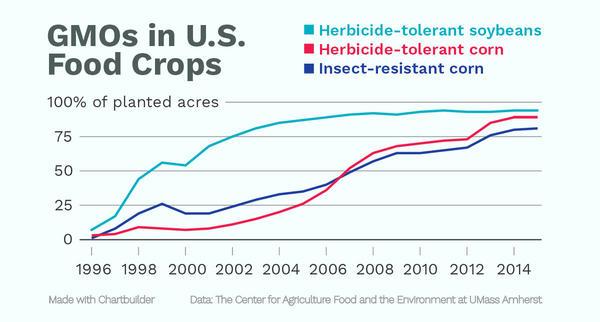

Other parents suggested the Gioscias change Ethan’s diet, so they began to scrutinize everything they fed him. First they cut out sugar. Then they switched to all organic food. Next they started researching genetically modified organisms [GMOs] — crops engineered with spliced genes to make them more resilient, or just bigger. The majority of corn and soybeans consumed in the US today are GMOs.

The information Mike and Linda found was overwhelming, unclear, and confusing, so they made their own call. Even without scientific evidence of harm, they decided to cut out GMOs.

"Now we’re at the point where all the answers come from us," Mike said.

But deciding to cut out GMOs and actually being able to do it are two different things. It can be hard to tell what food was genetically modified. Most companies don’t list GMOs on food labels. But parents like the Gioscias are forcing the issue.

"We didn’t start waking up till [we had] kids," Linda Gioscia said. "And I think that’s the same path for a lot of people, because all of a sudden you’re responsible for this being."

Lawmakers are feeling pressure to take action. Several states are considering bills mandating GMO disclosure. The US Senate, however, might be moving in the opposite direction. It’s set to consider legislation that would ban states from mandating listing GMOs on food labels.

Breaking down the science

"The food label is a very important battleground,” said Walter Willett, a Harvard University professor of epidemiology and nutrition who wrote the book on healthy eating ("Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy: The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healthy Eating") for Harvard Medical School. Willett said there’s no evidence that GMOs have a direct impact on health.

"I think we’ll almost never be able to make a general statement about GMOs being good or bad for us," he said. "This is a technology, and like most technologies, you can use it for good or you can use it for bad."

Despite the lack of information one way or another, Willett thinks people have a right to know if GMOs are in their food.

"How can you withhold information people would like to have, even though interpreting that information may be difficult at this point in time?” he asked. "I think it’s reasonable for someone to say, 'I prefer to not eat crops with GMOs,' just given some uncertainty, even though we haven’t proved that they’re different in terms of health consequences.”

If companies are forced to put GMOs on food labels, the big question is how consumers will react. Remember trans fats, the artificial fats used in packaged foods like chips and candy bars? Willett and other researchers found they raised cholesterol and the chances of heart disease. He was among the scientists who pushed the federal government to label foods that contain trans fats.

"Once it had to be on the label, the main manufacturers took it out of their products," Willett said. "So we've had probably about an 80 percent reduction in trans fat in our food supply."

But some biotechnologists warn against demonizing GMOs without understanding their benefits. GMOs, they say, could play a big role in what many see as the major food problem facing humanity in general — the world’s exploding population. There’ll be 2 billion more people on the planet by 2050, according to the United Nations, and we’ll have to grow a lot more food to feed them. GMOs could help us grow more food in sustainable ways that don’t harm the environment, says said G. Philip Robertson, a professor of ecosystem science at Michigan State University.

"GMOs can reduce the need for as many toxic pesticides, herbicides and insecticides," Robertson said. "They can also, perhaps in the future, provide more drought-tolerant traits [in crops]."

But the Gioscias aren’t focused on world hunger. They’re thinking about Ethan, and the changes they’ve seen in their son after years of eating a mostly organic, non-GMO diet. They said doctors have told them Ethan, who’ll be 12 in November, is no longer on the autism spectrum. He’s moved out of most special needs programs at school. Linda wept while remembering a recent parent-teacher conference.

"You’re just hoping for any good news, and she said, 'He’s right in the middle of the class,'" she said. "And your jaw just drops thinking, 'He’s right in the middle now. We were just hoping he could be in this class, never mind at that level.’”

Related: Hospitals are finding the right medicine in locally grown foods

The Gioscia family lives in rural Plymouth County, Massachusetts, about an hour southeast of Boston. They raise chickens and have a farm nearby, but it isn’t easy maintaining their diet. Sometimes the kids push back a little. They know not everyone eats the way they do. So Mike and Linda said they’re spending more time with families that make the same food choices.

"It’s easier to go to a barbecue with friends who are like you," Linda said.

It’s just another change the Gioscias have accepted as they prioritize parental instincts and their children’s future over unclear science.

A version of this story first appeared on WGBHNews.org. This story is part of a partnership between WGBH News and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences exploring the issues around our food. You can find the entire series here.