Philippines project turns ‘ghost’ fishing nets into carpets

Abandoned "ghost nets" take a deadly toll on fish and aquatic ecosystems around the world. The NetWorks program in the Philippines attacks the problem by paying fishermen to haul up old nets and then sends them to Europe and the US to be recycled into commercial carpeting.

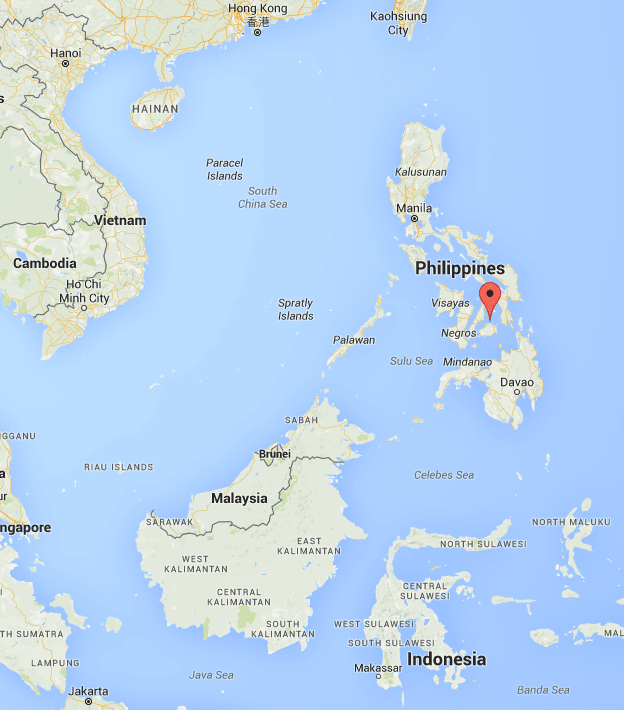

Just off the coast of tiny Guindacpan island in the central Philippines, a half dozen men in torn T-shirts and homemade flippers hold their breath and dive off a wooden boat to the sea floor 20 feet below.

They’re fishermen, raised to live off the sea like generations before them. But when they pop up to the surface every few minutes, it’s not with their usual catch. On these dives, they’re bringing up old fishing nets, dripping in mud and tangled with broken corals and dying crabs.

Lost and discarded nylon fishing nets like these are a huge problem around the world, estimated at roughly 10 percent of the millions of tons of plastic trash in the world’s oceans. And the Philippines is one the worst offenders.

But these fishermen may be helping to turn the tide.

“The nets that get thrown in the sea, it turns out they have a severe effect on the ocean,” explains fisherman Julius Sabal. “We sea people didn’t know before what these nets did.”

What they now know is that these ghost nets, as they’re often called, sit on the ocean floor and snag and kill marine life, including some of what would be the fishermen’s catch.

It’s competition they can’t afford. The Philippine government estimates that subsistence fishermen already catch only ten percent of what they did 40 years ago.

The ghost nets also have a big indirect impact on the coral-based ecosystems that the fish depend on.

“The fish are also disappearing because the nets are killing the coral reefs,” Sabal says. “Because it turns out the coral reefs can’t breathe when this is piled on top of them.”

Sabal and his fellow fishermen learned all this from the Zoological Society of London, a conservation group active in the Philippines.

But their new understanding hasn’t made the fishermen decide just to pull up the nets in their free time. They’re getting paid for hauling up the old nets, as part of a program called NetWorks, run in part by the ZSL.'

NetWorks tries to cut into the ballooning volume of marine debris worldwide by cutting fishermen a deal to turn old fishing nets into plastic carpet tiles. It spans the globe from the Philippines to Europe and the United States, but Amado Blanco, the program’s Philippines project manager, says the payments to fishermen are its most important element.

Blanco says he’s often seen people’s enthusiasm for volunteer conservation projects lose out to the more pressing needs of daily life.

But what can motivate people to support models like NetWorks in the long term, he says, “is that they can clean the environment and earn at the same time.”

And the money to pay the fishermen ultimately comes from the nets themselves. The ghost nets recovered from the waters off Guindacpan are baled up and shipped off to become part of the global plastics supply chain — first to a recycling facility in Slovenia, then to factories in the US and Italy where they’re turned into carpeting tiles.

Blanco says the program works because it feeds into a market that already exists, not because it makes people feel good to recover the nets or buy the carpet, or because some foundation supports it.

You could call it a kind of conservation capitalism.

“We don’t have to be dependent perpetually on funding from abroad or locally,” says Blanco.

The goal of the program, launched here in the Philippines in 2012, is to become a self-sustaining business, and it has already been successful enough that it’s expanding across the Philippines, into nearby Thailand and Indonesia, and even to a lake in Cameroon, in Central Africa.

Georgia-based carpet maker Interface, the company at the end of the pipeline, hopes it’s all just a start. Interface Vice President and Chief Innovation Officer Nigel Stansfield believes the NetWorks model can ultimately help solve the global plastic trash problem.

“In my dreams I see us mining the plastic soup in the North Pacific and the Atlantic with a group of like-minded organizations and industries and recycle that soup back into a variety of different sources,” Stansfield says.

“It's not beyond the wit of mankind to be able to do that. It's about will.”

Stansfield says it’ll take time to work out a business model that would be able to operate on such a large scale. And even here in the Philippines, the problem is much bigger than just old fishing nets. The sea here is full of plastic: shopping bags, water bottles, raincoats, children’s toys, toothbrushes, cell phone cases, potato chip packets.

For now, the ghost nets hit the sweet spot for this new approach. They’re a bad problem, many are relatively easy to recover, and they can be recycled into marketable products.

The people who buy and use the carpets the nets get turned into may never know they’re helping restore a working ecosystem halfway around the world, but the impact is tangible for the families of fishermen like Julius Sabal.

“The money helps us buy school supplies,” Sabal says. “Pencils, pens, this helps out for our kids.”

The effort also employs local women, who help collect and clean the old nets before selling them to the recyclers. The women have in turn set up savings and loan clubs to pool the money they earn from the work to disburse loans to help start small businesses or fund other short-term needs.

And then there’s the impact on the sea itself, and the generations-old livelihoods people here have earned from it.

“We’re taking the nets back from under the sea so that we can bring back the fish that used to be here,” Sabal says. “Because if we continue to neglect it, the oceans will be even worse for our children.”