Fracking is about to change, and almost no one is happy about it

Under the new federal fracking rules, wastewater must be managed onsite and in closed tanks, not in the open pits seen here.

The Obama administration recently announced new rules to regulate fracking. But no one, it seems, is entirely happy with them.

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is the process of drilling and injecting fluids into the ground at high pressure to break up shale rock formations and release natural gas that's trapped inside. The practice has helped make the United States the world’s top producer of oil and gas, and has spurred an economic boom in places like North Dakota. But it’s also become a prime source of water contamination across large areas of the country, and has inspired more than a few predictably cheeky protest signs.

The new, controversial regulations — some members of Congress, especially those from areas where fracking is more common, are opposing the rules — will take effect in June. In the meantime, ProPublica's environmental reporter, Abrahm Lustgarten, tells us what we need to know about the changes.

1. What are the new restrictions?

The regulations update existing rules, and are intended to protect groundwater from waste spills at fracking sites. “They're aimed squarely at insuring that wells are constructed well,” Lustgarten says.

They include requirements for how the cement casting on the wells must be installed and tested. Companies will also be required to do a geological analysis of the area around the well to determine if there are natural fault lines or “anything else underground that might allow chemicals or fluids to leak into a surrounding or nearby aquifer,” Lustgarten says,

It’s not just the wells that are regulated. The rules also govern how companies can store the waste that fracking produces.

“They'll require that waste temporarily be handled at fracking sites in closed containers, basically in steel tanks instead of the open waste pits that have also been associated with groundwater pollution across the country,” Lustgarten says.

2. What parts of the country will be affected?

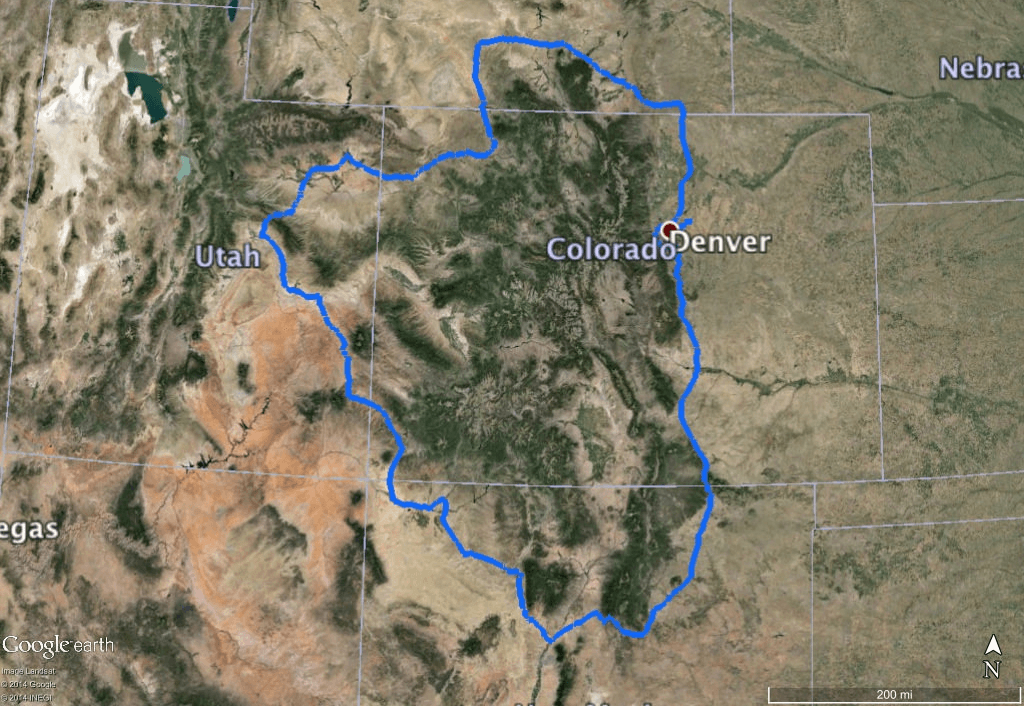

The rules only apply to federal land, which contains about 100,000 wells. That represents 10 percent of the fracking that's happening in the United States, according to Lustgarten.

The most significant area affected is the Bakken Shale, a large reserve of natural gas and oil between Eastern Montana and Western North Dakota. Central Wyoming, Northern Colorado, and parts of California also have large tracts of federal land. Along with the existing wells, “there will be new wells coming in the future, and they will all be subject to these rules,” he says.

3. What does the industry say?

In a move that surprised absolutely no one, the oil and gas industry quickly voiced its opposition to the new regulations. The American Petroleum Industry immediately filed suit to stop the rules from going into effect.

“The industry, across the board, has said repeatedly that it will be expensive and onerous and will probably disincentivize investment and drilling on federal lands and lower federal income related to that drilling and so forth,” Lustgarten says.

But he's not entirely buying the industry’s argument. Lustgarten notes the industry itself estimates that the new rules will cost companies 1.5 percent of the cost of drilling a well; the Department of the Interior estimates the cost as low as one-tenth of one percent. The total cost around the country comes out to $350 million dollars a year, an amount Lustgarten says is “very insignificant” compared to the “tens of billions of dollars in profits for each of these companies.”

He also points out oil and gas companies have successfully adjusted to similar regulations in states like Wyoming. “I just don't see these new federal rules as being too much of a roadblock to industry,” he says.

4. So are the environmentalists happy then?

No surprises here, either: Environmentalist groups see the new regulations as a step forward, but they want more.

“Their central criticism is the Obama administration has taken a path towards addressing climate change and that hydrocarbon development should not be allowed on federal lands,” Lustgarten says.

An all-out ban isn't in the cards, but environmentalists still want the rules to go further than they do now. For instance, they want to force companies to disclose all the chemicals used in fracking without any caveats. They're also caling for the technical specifications around well construction to be even more stringent.

5. So how important is this, at the end of the day?

Lustgarten characterizes the overall impact of the new rules as a “mixed bag.” The Obama adminstration is “setting a baseline” for what’s acceptable, he argues, and providing an example for states and even companies to follow.

And by forcing companies to be more transparent about the chemicals used in fracking, Lustgaren thinks the regulations will lead to a more informed discussion about the practice.

“With the advent of these federal rules, there will be a public record that can be searched and requested and analyzed," he says, "and should we have to look back again, there will be a lot more information to work with.”

This story originally aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.