NASA’s Dawn spacecraft is already historic, and it’s just getting started

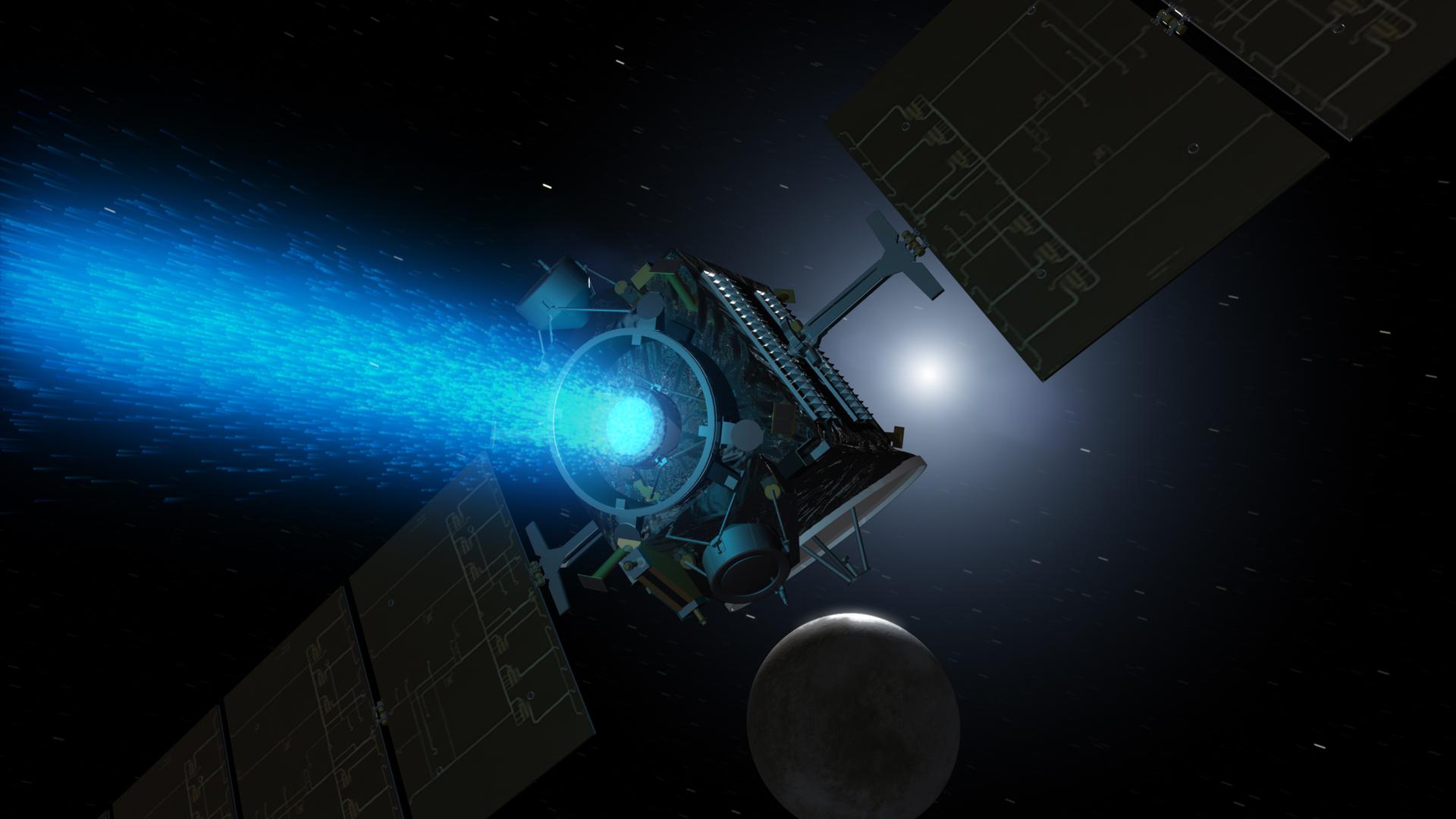

This artist's concept shows NASA's Dawn spacecraft arriving at the dwarf planet Ceres (lower right).

In terms of big unanswered questions in our planet’s history, you don’t get much bigger than “How did life start?” It certainly didn't start without water, and the latest turn in a seven-year NASA mission may bring scientists closer to understanding how that vital subtance, one of the building blocks of life, got to Earth.

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft became the first ship to achieve orbit around a dwarf planet when it swung into the gravitational pull of Ceres last week. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, has water. If scientists can glean clues as to how it got there, they might come closer to more definitely answering the same question for our planet.

“Ceres has a large inventory of ice. It may even have some liquid water,” says mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman. "We don’t know that yet, but it’s one of the things we want to investigate. And of course, I think many people know that there is a big question about how Earth got its water. Well, maybe by exploring Ceres we’ll learn more about that.”

Dawn is also the first spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial targets. Its first stop was the giant asteroid Vesta, also part of the main asteroid belt, which it orbited in 2011 and 2012. The images Dawn captured showed scientists that Vesta more closely resembles a planet than other asteroids — and that it had completely melted in the past

Scientists consider both Vesta and Ceres to be “protoplanets,” bodies that form planets when they collide and combine with each other. The pull of Jupiter stopped that process for Vesta and Ceres, but Dawn’s mission could help scientists better understand Earth’s development.

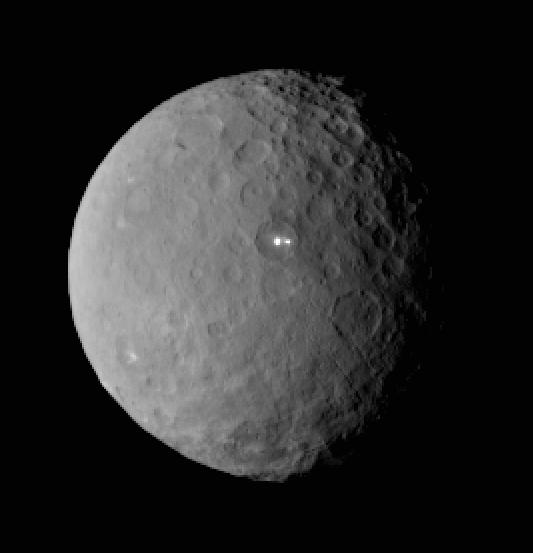

Based on recent developments, Rayman and his team also have a more specific goal in mind for Dawn. On Jan. 13, the spacecraft captured an image showing two bright spots on Ceres' surface. Scientists aren’t sure what’s causing them, but Rayman hopes that Dawn will help them get to the bottom of it as it begins to take higher resolution pictures in the coming months.

“They are just these sort of glowing beacons shining out from the uncharted landscape ahead, and the answer to your question of what they are is we don’t know,” Rayman says. “It makes you want to send a spacecraft there to find out.”

There's one more first for Dawn: It got to Ceres using an electrically powered ion engine. It's the first exploratory spacecraft to use one, which is an important development for space exploration. The experimental Deep Space One probe first demoed the engine back in 1998. As NASA explains, Dawn's “thrusters work by using an electrical charge to accelerate ions from xenon fuel to a speed 10 times that of chemical engines.” A more efficient engine means a lighter and cheaper spacecraft, and a much smoother ride.

"You’re used to thinking of a spacecraft coming screaming up at high velocity, you know?" Rayman explains. "And it executes this bone-rattling, whiplash-inducing burn into orbit. But Dawn just very, very gently, gradually, elegantly slips into orbit, maneuvering in a complex route that would be the envy of any crackerjack spaceship pilot.”

This video from NASA helps show what Dawn's path looked like:

Dawn is on the dark side of Ceres until April, when it will begin spiraling closer to the dwarf planet and sending back more images and data for NASA scientists to pore over. It’s mission will last a year, but Dawn will be in Ceres' orbit long after its last transmission home.

“We’re going to be exploring it for about a year, but it’s going to be in orbit effectively forever,” Rayman says. "We’re not leaving. We’re there to stay.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Dawn was the first space probe to use an ion engine. While it is the first exploratory probe to do so, the experimental Deep Space One probe first demoed the technology in the 1990s.