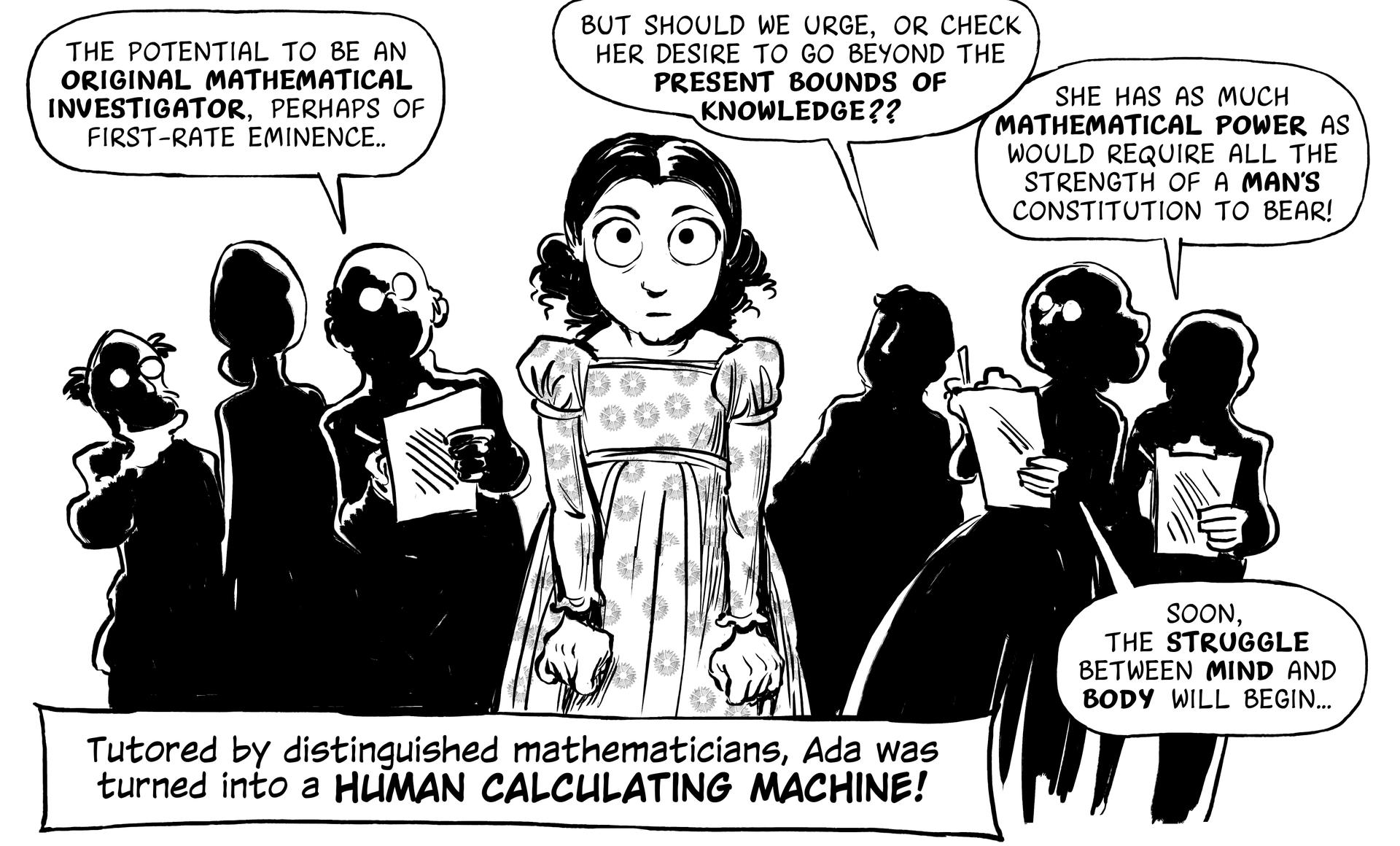

A panel from "The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage" graphic novel.

Ada Lovelace was born famous: the daughter of celebrated poet Lord Byron. Often considered the world’s first real rockstar, Byron’s wild lifestyle and sexual exploits helped define modern celebrity.

Ada’s mom wanted none of it. To prevent her child from acquiring her dad’s crazy temperament, she banned poetry and educated her daughter strictly in the logic of mathematics.

When Lovelace was 18, she met and impressed the famous mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage. He was designing a calculating machine he called the analytical engine, and Lovelace fell in love with it. The two became friends and collaborators.

Had the engine actually been built, it would have been the world’s first general purpose, programmable computer — steam-powered and constructed with cogs, gears and wheels.

Babbage saw the engine as a tool for advanced arithmetic, but Lovelace saw a lot more potential.

“She saw the connection that actually Babbage’s machine didn’t necessarily have to deal with numbers," says Sydney Padua, a visual effects artist who’s dug deep into the archives and written a graphic novel on the adventures of Babbage and Lovelace. "She had this enormous leap of insight that actually the machine wasn't a mathematical machine — it was logic machine, which actually made it capable of using any kind of information, not just mathematical information.”

As a woman in Victorian England, though, it wasn’t quite proper for Lovelace to publish a paper of her own ideas. Instead, she translated the only paper ever written about the machine from French to English — and added her own notes, which were twice as long as the original paper.

“It’s in the footnotes that she kind of writes down the first published description of computer science. Like how information can be manipulated by a machine,” Padua says.

And in those notes, Lovelace also writes the first computer program. Lovelace died young, after a long illness. Her writings and Babbage’s engine were pretty much forgotten.

Famous computer scientist Alan Turing was the first person in the modern computer age to reference Lovelace in his own writings. She was later hailed as the world’s first programmer and a visionary who saw the potential of modern computers 100 years before they were built. In 1980, the US Defense Department named a programming language after her. And then in the mid-80s, the backlash started, says computer scientist Valerie Aurora.

“In 1985, there was this incredibly vicious biography which claimed that she was just delusional, on drugs and a gambler, had way too high of an opinion of herself, and therefore could not have possibly written the first computer program," Aurora explains. "Charles Babbage must have written it for her.”

Babbage scholars often lead the attacks, weary of Lovelace "stealing" his spotlight. Any errors in her math were seized on as proof she couldn’t have written the paper. Padua, who writes equally about both, says the two inspired each other, and the documents don't make sense if Lovelace didn’t write it.

The fact that Lovelace was probably bipolar, maybe slept around, and used opium as a pain-killer (like a lot of Victorians) are all kind of besides the point.

Padua and Aurora, who both work in tech, say the anti-Lovelace rhetoric sounds eerily familiar. From 2014.

“Look at my life. How many people were trying to insist to me that I wasn't actually good at programming or doing the work that I had done?” Aurora asks.

In 2010, Aurora started the Ada Initiative, an organization that works to support women in tech. “I co-founded it after a friend of mine was groped for the third time in one year at an open source conference," she adds. "And when she complained about it on her blog, hundreds of people threatened her with rape and death threats.”

What we now call Gamergate has actually been going on for a long time.

“We had been working on a volunteer basis to get more women involved. And I just — that broke me. I couldn't encourage women to go into a field where I knew they could get sexually assaulted three times in one year just for doing their job,” Aurora says.

Lovelace is now getting her due, generally accepted as the world’s first programmer. There is now an international Ada Lovelace Day, and a medal for achievement in computing named in her honor.

She’s become something of a patron saint for modern computing — a symbol of what women are capable of, and a symbol of the fight for respect, acceptance and an equal place at the table, 150 years ago and today.