Here’s the impossibly complicated way calculators used to look

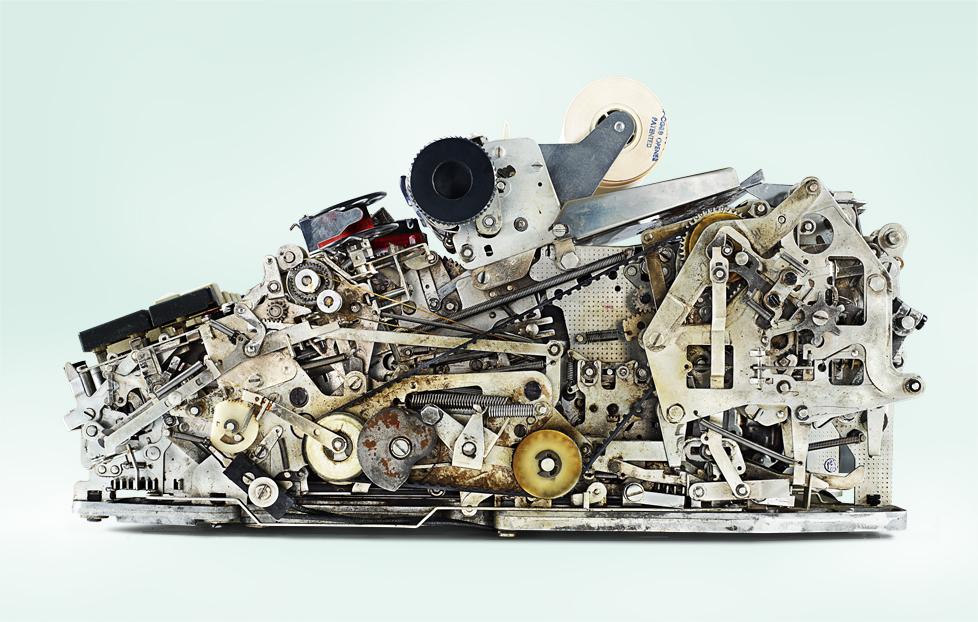

An image of the Monroe PC-1421 with its cover removed.

Mark Glusker had heard rumors about the mechanical calculator, a Monroe PC-1421; that it was one the most complicated devices of the sort ever built; that it was powerful but notoriously difficult to keep running; that it was at the pinnacle of an effort to compete with the first electronic calculators.

“It’s kind of a holy grail machine for me,” says Glusker, a mechanical engineer and collector of early calculators. “When you’d read the specifications, you’d think, ‘That’s just crazy.’” And once he finally got his hands on the 40-pound behemoth from a retiring professor at the University of Iowa, it proved just as intricate as he’d imagined.

“There’s so much going on inside there,” says photographer Kevin Twomey, who photographed the PC-1421 and other calculators in Glusker's collection. “These chains, levers and gears were almost reminding me of how ligaments and joints are working together."

The Monroe PC-1421, with a price tag of $1,175, at the top end for a mechanical calculator, debuted in 1964 — right as electronic calculators were overtaking mechanical ones. To stay relevant, manufacturers constantly fought to improve the speed of their machines. For instance, while early mechanical calculators required an operator to turn a crank by hand in order to add, subtract, multiply, and divide, later models like the PC-1421 turned automatically with a motor.

Whenever the company came up with an improved part for the calculator — which contained thousands of pieces and frequently broke — service managers had to fan out to disassemble, reassemble, and recalibrate the entire device in order to incorporate the new part. That happened every couple of weeks.

Glusker tracked down a former Monroe service manager, who “recalled the machine with a mixture of awe and dread."

And every mechanical calculator was uniquely complex. Glusker, who has around 100 calculators in his collections, explains that when manufacturers started producing the machines in the 1930s, there was no standardization. The machines “evolved completely differently, with different mechanisms.”

While engineers primarily used more complicated mechanical calculators like the Monroe PC-1421 — many in Glusker’s collection came from thrift stores near national labs like Los Alamos — shopkeepers and financiers relied on the simpler devices.

Twomey, a commercial and fine arts photographer, had been doing research on calculators for a different project and became curious about the variety, complexity, and bold industrial design of the mechanical devices from the ’50s and ’60s.

When Glusker removed the outside casing from one of his machines for a demonstration, Twomey instantly knew that he had a compelling subject matter for a new photo series.

Despite the efficiency mechanical calculators provided, however, electronic ones eventually edged them out in the end — the new machines were faster, quieter, cheaper and ultimately more reliable. These days, collections like Glusker’s and photographs like Twomey’s are all that remain.

This story was originally published by PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?