What’s in a label? Not much, if it says ‘all natural’

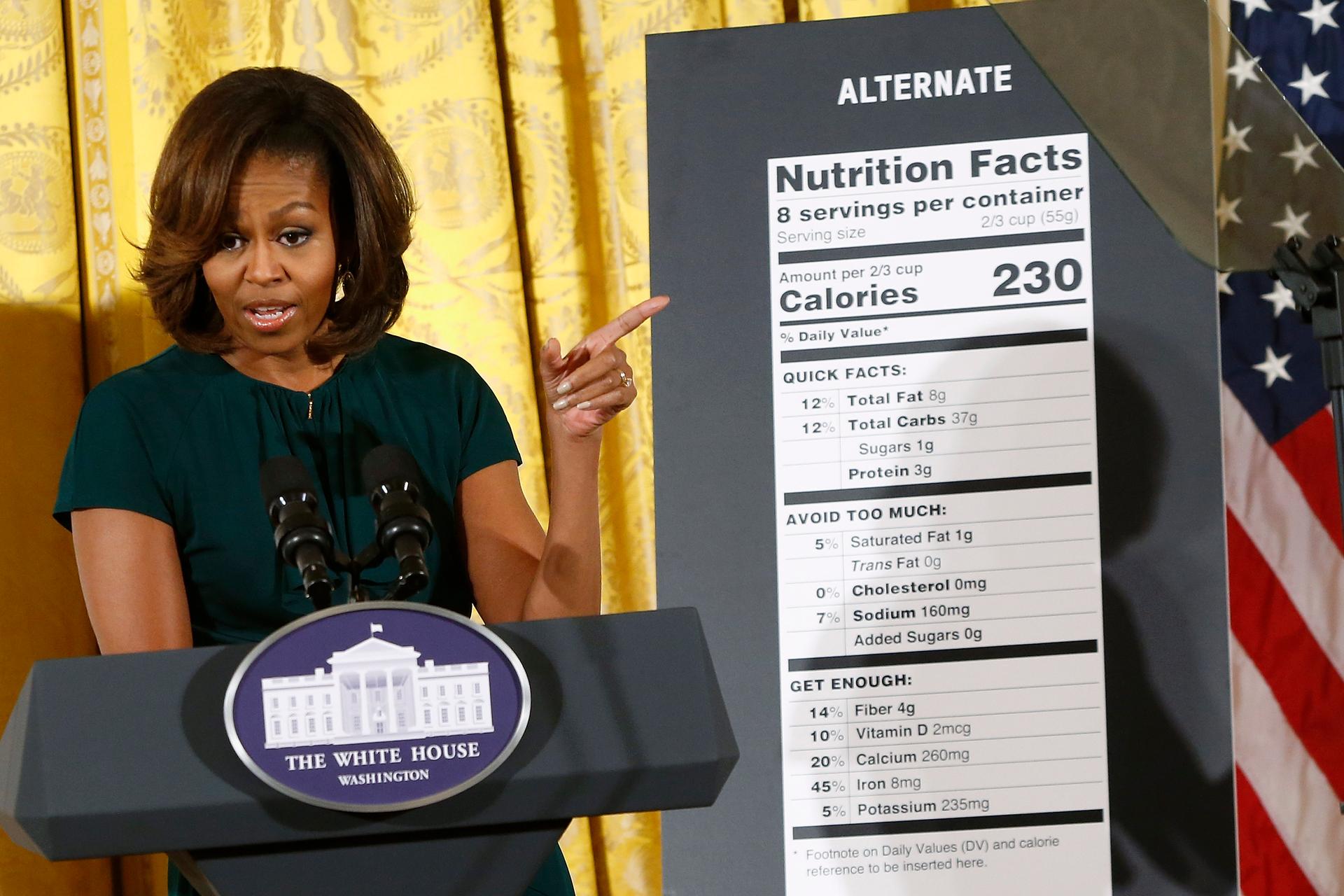

First Lady Michelle Obama unveils proposed updates to nutrition labels during remarks in the East Room of the White House on February 27, 2014.

It's been a busy year for food labels.

In May, Vermont legislators voted to make GMO labeling mandatory in the state, which sparked a lawsuit from a coalition of companies that includes Starbucks. Meanwhile, during the midterm elections earlier this month, ballot initiatives to require mandatory GMO labels failed in Oregon and Colorado.

There's also another big labeling question coming before the Food and Drug Administration, one over what food can be considered "natural." How do labeling rules get made, and when is something "natural," really?

Americans are increasingly looking for natural foods — according to a 2013 survey conducted by The New York Times, about three-quarters of Americans are concerned about genetically modified organisms in their food. But from a food science perspective, it is difficult to define a food product as “natural.”

That's because because many foods are processed in some way, which means it “is no longer [a] product of the Earth,” according to the FDA — which is why the government agency has not yet developed a definition for use of the term natural or its derivatives

“The problem with ‘natural’ is that it’s not a science issue,” says Richard Williams, a former FDA director for social sciences at the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. “It’s definitely a marketing statement.”

Williams, the current vice president for policy research at George Mason University's Mercatus Center, says "the law is pretty clear about what has to be on the food label. Congress passes the laws, and the FDA passes regulations that require information to be on the food label. In general, the information that they require is based on science.”

But he also says that food companies get to have some input on what goes on those labels.

“Anybody can petition the Food and Drug Administration for a change they want to see on the label,” he says. “The FDA then goes through the process of taking in all of the comments, ensuring that it’s consistent with the law, and then they can choose to either require it or not require it.”

That's how you can end up with statements like “all natural,” along with scientifically meaningless claims on products like “Supports Bone Health."

“It’s a non-scientific issue,” Williams says. “Do we really want the Food and Drug Administration to certify sugar as natural but then hold high-fructose corn syrup as artificial? Both are nutritive sweeteners, both are manufactured. … I think the FDA has a hard enough job just trying to get the food label and the science right without taking on these issues.”

This article is based on an interview from PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.