William Wells Brown may be the most famous 19th century African American writer you’ve never heard of

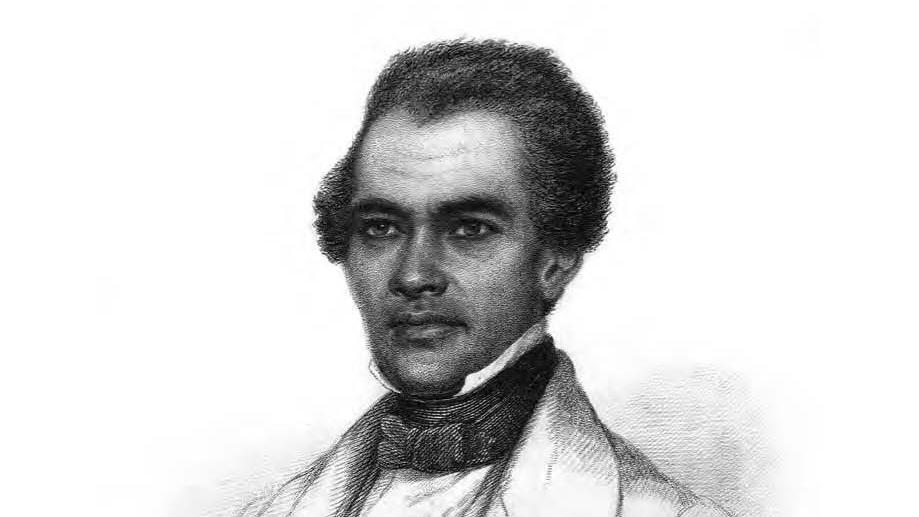

An engraving of William Wells Brown in London. This was published in his book, "Three Years in Europe." No photo of Brown has ever been found.

William Wells Brown has the distinction of being the first African American novelist ever to be published — in 1853.

Brown wrote “Clotel” during five productive years in Europe in which he experienced a freedom that wasn’t possible in America. His novel is taught in some college classes today, but many people don’t know him.

“He was erased, to a very large extent, from the public record,” says Ezra Greenspan, author of the new biography, “William Wells Brown: An African American Life.” “It was nothing personal or particular. He was erased the way virtually all African Americans were — their presence, their culture. And he really only came back into existence with the civil rights movement.”

Brown was born a slave in Kentucky around 1814. For many of his early years he was enslaved in Missouri. But by the time he was 19 years old he had been sold to a Mississippi River steamboat owner. While in port at Cincinnati, Wells Brown escaped – traveling in the Ohio countryside, by foot, in the January cold.

“He took his life into his hands,” says Greenspan. “He stopped a good Samaritan-looking figure, a person wearing a wide-brimmed hat, clearly, identifiably a Quaker.”

The Quaker took him in and offered William the gift of a complete name, his OWN name: Wells Brown. In gratitude, the runaway slave went by the name William Wells Brown for the rest of his life.

After two weeks, Brown kept going north, eventually settling in Boston. In the following years, he rapidly rose to prominence as an anti-slavery speaker and the author of a powerful slave narrative, “Narrative of William W. Brown.”

As a black man, and a fugitive slave, he had more freedom in the North, but he certainly wasn’t free.

“What we mean by freedom really is a relative term,” says Greenspan. “Brown would say repeatedly: if one wanted to be free, absolutely free, one needed to go to England.”

And he did, like his abolitionist colleague Frederick Douglass before him.

“Slavery had been abolished in England and France. They could have a wider scope for their actions and their thoughts than they could presumably have in the United States, ” Greenspan says.

Brown left for Europe intending to stay only a few months. With London as his home base, he traveled extensively and freely in England, Ireland, Scotland and France. He spoke before large, receptive crowds. He developed close friendships with blacks and whites — in the anti-slavery movement, in government, in his social life. He wrote a book about his European adventures, which in England was published in 1852 as “Three Years In Europe.” (It was published in America three years later under the title, “The American Fugitive in Europe.”)

And he wrote his novel, “Clotel,” about a mixed-race daughter of an American president. Even in the 1800s, rumors were floating around about Thomas Jefferson.

Creatively, and in every way, Brown was thriving.

“If you run forward 50, 60, 70, 80 years,” Greenspan says, “what Brown and Douglass were doing in the 1840s and 50s was what the next generations of black Americans would do. We think of Josephine Baker, as it were, finding her feet on stage in Paris. We think of James Baldwin living much of his mature life feeling free for the first time. But there actually was a long history that went back to the middle of the 19th century. Brown in some ways was a pioneer.”

He may have been a pioneer — but he couldn’t go home. Back in America, Congress had passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. That meant escaped slaves could be hunted down and captured — even in the north. Brown stayed in Europe four more years until a Quaker family in England, Ellen and Henry Richardson, raised the money to buy his freedom. The Richardsons had done the same thing for Frederick Douglass a few years earlier.

“He was a free man, and he did not wait,” Greenspan says. “As soon as the freedom papers arrived in London, Brown was on one of the first steamships out of Liverpool and right back into his life in the Boston area, but on a fundamentally different basis.”

As good as life was in Europe for Brown, the anti-slavery battle was raging in America. That’s where he needed to be. After emancipation, Brown continued his fight against injustice through his writing and public speaking. And he reinvented himself yet again — becoming a medical doctor.

UPDATE: This story has been updated to reflect that William Wells Brown escaped and travelled on foot from Cincinnati to somewhere between Cincinnati and Cleveland. He did not walk from Missouri to Ohio.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?