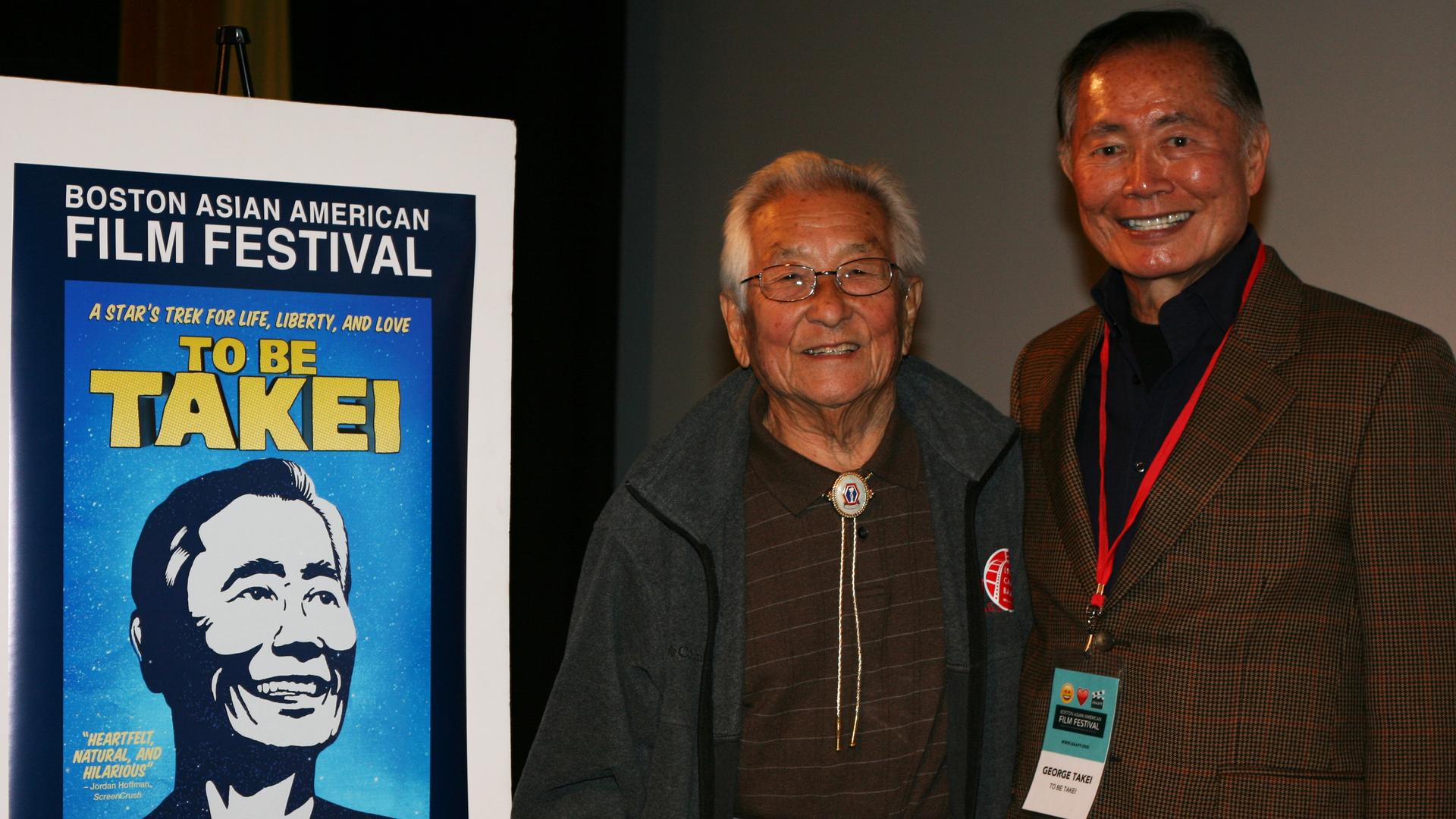

George Takei, an actor, activist and the star of the documentary "To Be Takei," spoke about the early part of his acting career, when he regretfully took on roles that furthered Asian stereotypes.

You may know George Takei as Mr. Sulu from Star Trek, but his own life here on Earth was “transformed as fantastically as science fiction," as he puts it.

“As a boy I looked out on the world imprisoned behind the barbed wire fences of American internment camps,” says Takei in his new documentary, "To Be Takei."

Takei was born in Los Angeles to Japanese Americans. So when World War II came, his family was taken from their home to a camp in Arkansas. In between was a three-month stop at the Santa Anita race tracks, where the five-person family slept on cots crammed into a horse stall.

“For my parents, it was the most degrading, humiliating, painful experience," Takei says, "but for me, as a kid, I thought it was fun to sleep with the horses." He was just 5 years old.

The US government forced all Japanese American adults interned in the camps to fill out what was called the “loyalty questionnaire.” The key item was question number 28, which asked, "Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America and foreswear your loyalty to the emperor of Japan?"

His father and his mother both answered "no" to question 28. "[My father] said they took my business, they took our home, they took our freedom — the one thing they’re not going to take is my dignity. I am not going to grovel before this government,” Takei remembers.

The family finally returned to Los Angeles in February of 1946, when Takei was 9. The transition back was anything but easy. "The hatred was still intense. It was right after the war,” Takei says. “No one would hire us. No one would offer us a place to stay.”

His family ended up living on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles. “And that, to us kids, was terrifying," he says. "At least behind those barbed wire fences we had a form of routine and normality, and here we were thrust out and thrown into this neighbourhood with the stench of urine everywhere.”

Takei couldn’t escape the discrimination at school, either: “The teacher continuously called me ‘The Jap Boy’ — a teacher! What had I done?”

When Takei began reading books about American democracy as a teenager, he questioned his father about their camp experiences.

“He was the one in our family that suffered the most, and yet he was able to tell me about the core value of our democracy," Takei says. "He said, ‘Ours is a people’s democracy and it can be as great as the people can be — but it’s also as fallable as people are.’”

But Takei will never forget a moment when he challenged his father about internment.

“I said, ‘Daddy, you led us like sheep to slaughter when you took us into the internment camp.’ And he was silent for many, many beats and I realized I had hurt him. I had touched a nerve and I felt terrible. Then he said, ‘Well, maybe you’re right.’ And he got up and went to his bedroom and he closed the door. I knew it was painful for him. This arrogant teenager, after he had suffered so much in the war, was again wounding him.”

Takei never was able to tell his father that he was sorry — he passed away in 1979. “That’s one of the regrets I have in life," Takei says.

The discrimination didn't really end when he made it to Hollywood, either.

Even well after the war, when overt anti-Japanese racism had waned, movie and TV roles for Asian Americans were rather limited and very often stereotypical. “There were waiter roles, servant roles, villain roles,” Takei says.

Takei talks in his documentary about the roles he felt compelled to take, like the stereotyped, thickly accented Asian diamond dealer in the 1967 Jerry Lewis film, "The Big Mouth."

“These are roles that I told my father that I would not do," he said. "I turned it down but my agent said, ‘Jerry Lewis is big box office. You’ve got a momentum going to your career and to keep that momemtum going you’ve got to be attached to a big box office movie.’ And so I did it. Ambition, I guess. My fallibility.”