Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga (third from the left) belonged to the Junior Misses, one of many Japanese American social clubs that often held dance performances.

Back in 1940s Los Angeles, members of a Japanese-American social club called Just Us Girls seized on the city's nightlife. The young women rode the streetcar to the Million Dollar Theater to see big bands and danced into the night to the tunes of Louis Armstrong.

Sumi Hughes, then known as Sumi Fukushima, was particularly lightfooted. "I always had boyfriends who were good dancers," 81-year-old Hughes explains. "That was a prerequisite."

From the 1920s through the 1950s, Los Angeles teemed with hundreds of social clubs for young second-generation Japanese Americans, or Nisei. That was especially true for girls. The clubs were a phenomenon that allowed the daughters of strict Japanese immigrant parents to explore their American identities — and ease wartime discrimination.

"I’m sure parents thought it was one way to keep an eye on their daughters and know who their friends were," says UCLA historian Valerie Matsumoto, who wrote "City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles." At their peak in the late 1930s, Matsumoto found that between 400 and 600 of the social clubs existed, mostly in California.

Some of the clubs were formed through friendships, others under the auspices of churches, Buddhist temples or YWCAs.

Thousands of Nisei girls joined these clubs to play sports, do community service and — unofficially — meet boys. The names for these get-togethers ranged from the Biblical —the Queen Esthers — to the Hollywood-inspired, such as the Swansonettes, named after actress and singer Gloria Swanson.

But the stories of these clubs are quickly fading as members age and die. "I turned 90 last month," says civil rights activist Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, who belonged to a club called the Junior Misses. "So I can see why our group has been decimated."

Filling a void

Matsumoto's book is the first to take an in-depth look at these social clubs. She says that racial tensions, coupled with rocky US-Japan relations, forced young Japanese Americans to create their own social circles.

"There was a lot of discrimination in public facilities," Matsumoto says. "So sometimes they weren’t able to go to certain restaurants or certain public venues."

After the Pearl Harbor bombing in December 1941, the principal of Herzig-Yoshinaga's high school called her and other Nisei students into his office. He told them they didn’t deserve to graduate "because our people had bombed Pearl Harbor."

"We said, 'What’s the connection?'" Herzig-Yoshinaga remembers. "We didn’t drop the bomb. We know nothing about it.”

Later, as an adult, Herzig-Yoshinaga would channel her anger and humiliation into the fight for reparations for Japanese Americans forced into government camps during World War II. But as a teen, she found immediate solace in the Junior Misses.

It was filled with other girls facing similar identity issues, "trying to be American [but] at the same time not knowing whether or not we like being Japanese because of the prejudice that existed so strongly," Herzig-Yoshinaga says.

Life interrupted

The Junior Misses broke up as Herzig-Yoshinaga and other members were forced into internment camps for Japanese Americans, which were scattered across the country.

But internment didn’t shut down all of the social clubs. Some, including Just Us Girls, were actually formed within camps. Sumi Hughes helped create that club with her older sister, Yuri Long, when their family was moved more than 200 miles north of Los Angeles to the Manzanar Relocation Center.

"That was our social life at the time," says Long, who was 9 when she first arrived at Manzanar. "You had to be in a club to have a sports team and to have dances.”

Just Us Girls lived on after World War II ended, with most of the club members and their families settling in the same Los Angeles neighborhood.

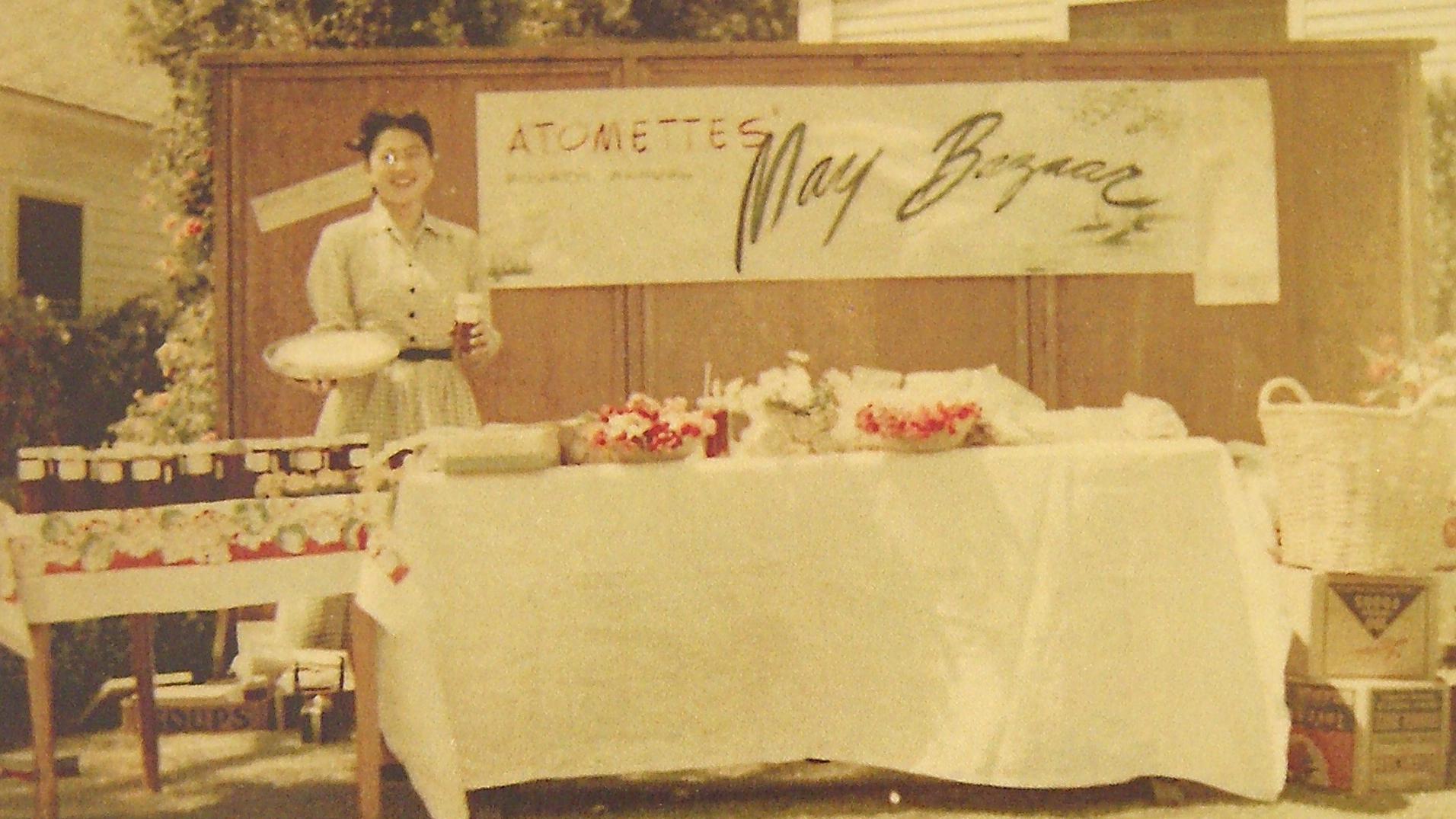

And other clubs, such as the Atomettes, formed right after the war. Rose Honda was a teenage advisor to the group of middle schoolers, which emerged from the West Los Angeles United Methodist Church.

"In 1945, we were all returning from the camps," says Honda, who's now 87. "We gathered the girls to form a club because their parents were busy resettling."

Honda says the group explored Southern California to learn about different cultures and see a world bigger than their own. "We could only put seven teenagers into the car and that’s the reason we stayed at seven," Honda said.

Almost 70 years later, Honda still gathers occasionally with the Atomettes. They're now working on a book about their history.

Every waking moment

Just Us Girls is one of the rare social clubs that still meets regularly, though they no longer go dancing. It’s usually a trip to Las Vegas once a year, and dinner and poker every few months at Sumi Hughes' place in Pasadena.

The stakes for the card games are very low. "Last time, I think I won 60 cents," Yuri Long says.

The women often stay up for 18 hours on poker nights, talking about their kids, grandkids. "I have the most kids, so I have the most stories about the kids," Long says.

Sumi Hughes said friends come and go, but not these women. "I know a lot of people, but I don’t know anybody I could feel this close to," Hughes says.

Every moment with them is precious, she says, so they stay up until daybreak, laughing and playing for pennies.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?