R.K. Laxman, cartoonist who chronicled India’s first 60 years of independence, has died

Editor's Note: R.K. Laxman, India's cartooning giant, died Monday at age 94. Here's a recent profile PRI's The World did about his impact.

There's a morning ritual in India that lasted for decades. Each day, millions of Indians would look at the cover of The Times of India to check in on The Common Man, the cartoon character created by cartoonist R.K. Laxman.

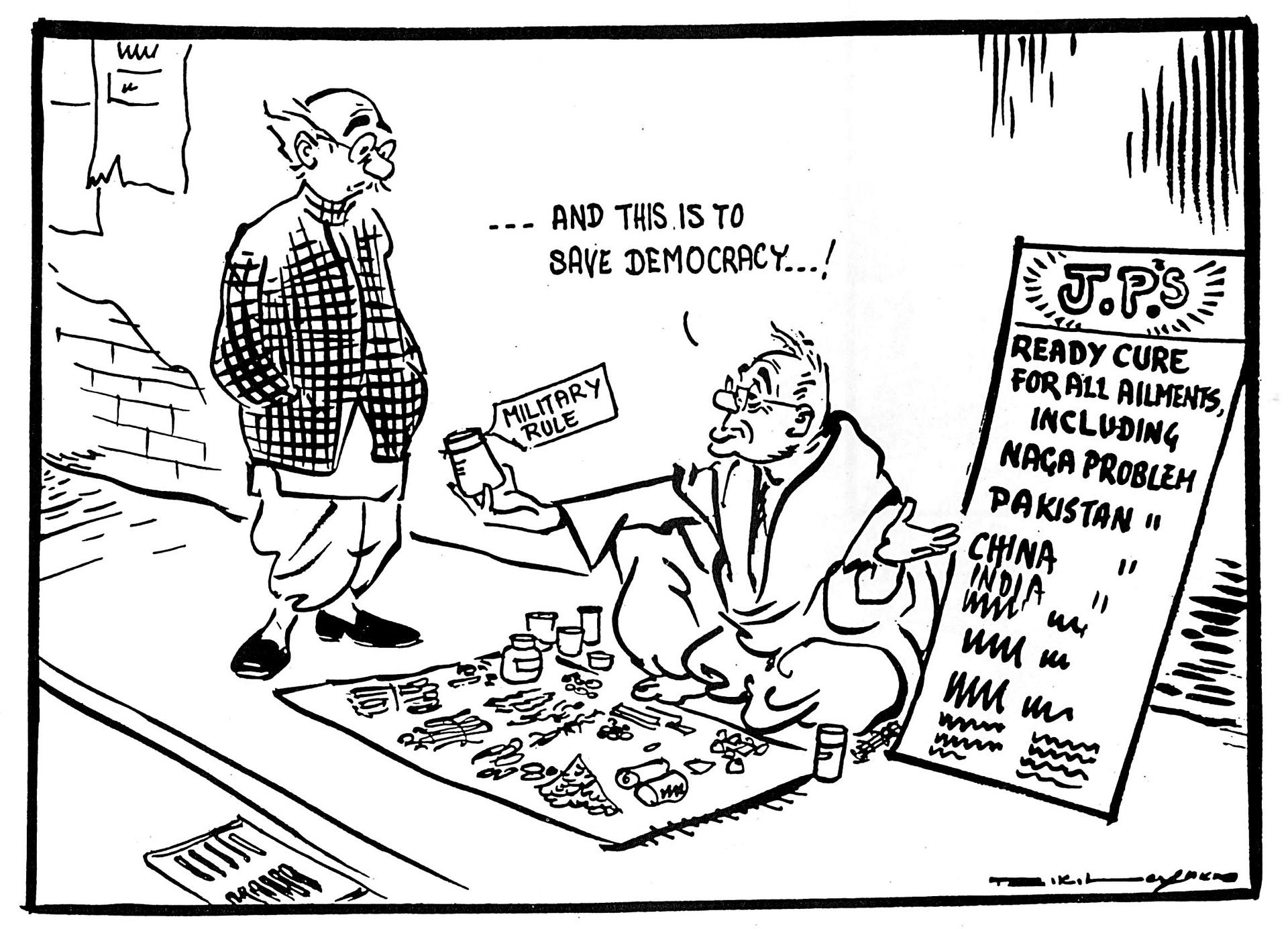

The Common Man represents the Indian everyman. By profile and looks, he's a villager: clad in a tattered checked coat, older, bald, with a white wisp of hair. His glasses are perched on his nose and he's in a permanent state of bewilderment as Indian politicians behave badly, citizens grasp for power and the country stumbles toward modernization.

Khanduri is now an academic who writes about the impact of political cartoons on Indian history. She interviewed Laxman, now 93, for her new book Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World. In Laxman's cartoons, The Common Man never speaks. Silently, he allows readers to witness the messy business of democracy up close, by bringing them into government offices, along the campaign trail of ethically-challenged political candidates and even into people's homes.

Laxman started drawing cartoons in 1947, the year India won its independence from Britain. He stopped cartooning several years ago after suffering a series of strokes. Collectively, his cartoons serve as a satirical chronicle of the first six decades of post-colonial India.

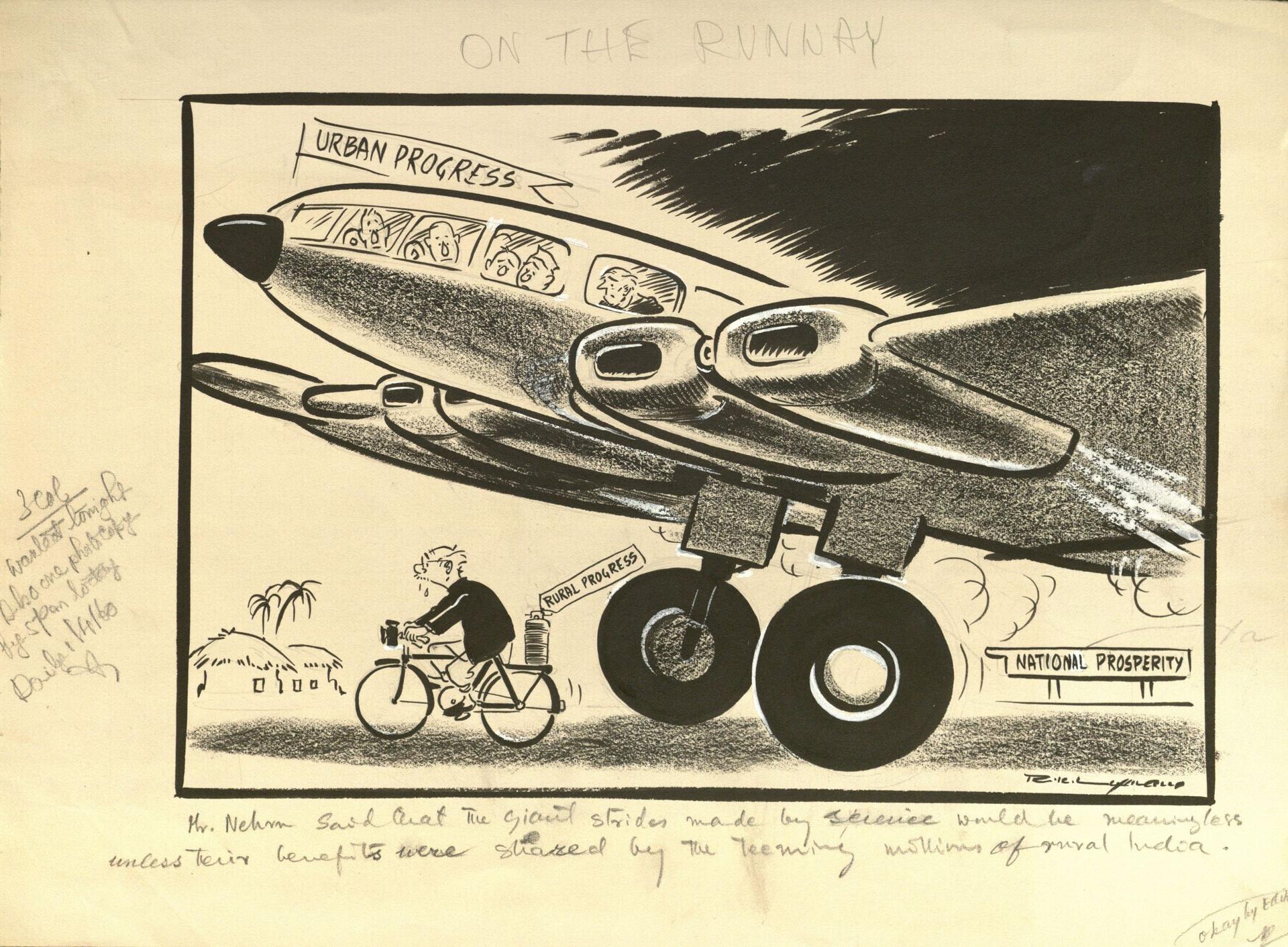

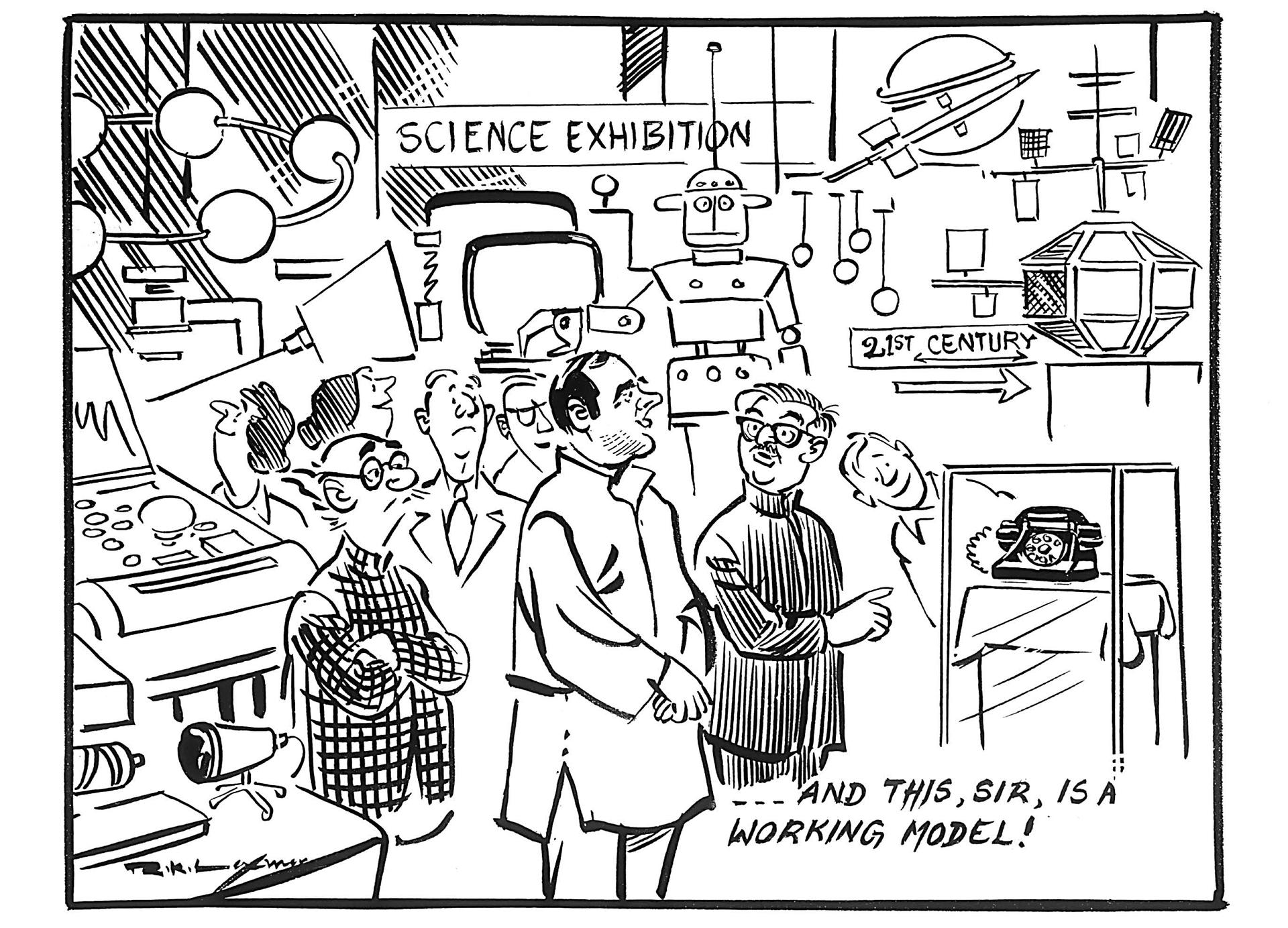

Among Laxman's favorite punching bags were modernization plans dreamed up by successive Indian leaders.

"[Laxman] would puncture their aspirations and the way that development was modeled and show the disparity between rich and poor," Khanduri says. India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, had a plan for a national airline. "Whereas if you go to the villages, the vast majority were still struggling with more archaic forms of transportation, like the bullock cart. So there's this gap between what is aspired for and what is actually happening at the ground level."

Khanduri says Laxman's cartoons animated this gap and constantly asked the question: Who is modernization for and can all participate and have equal access to this modernization.

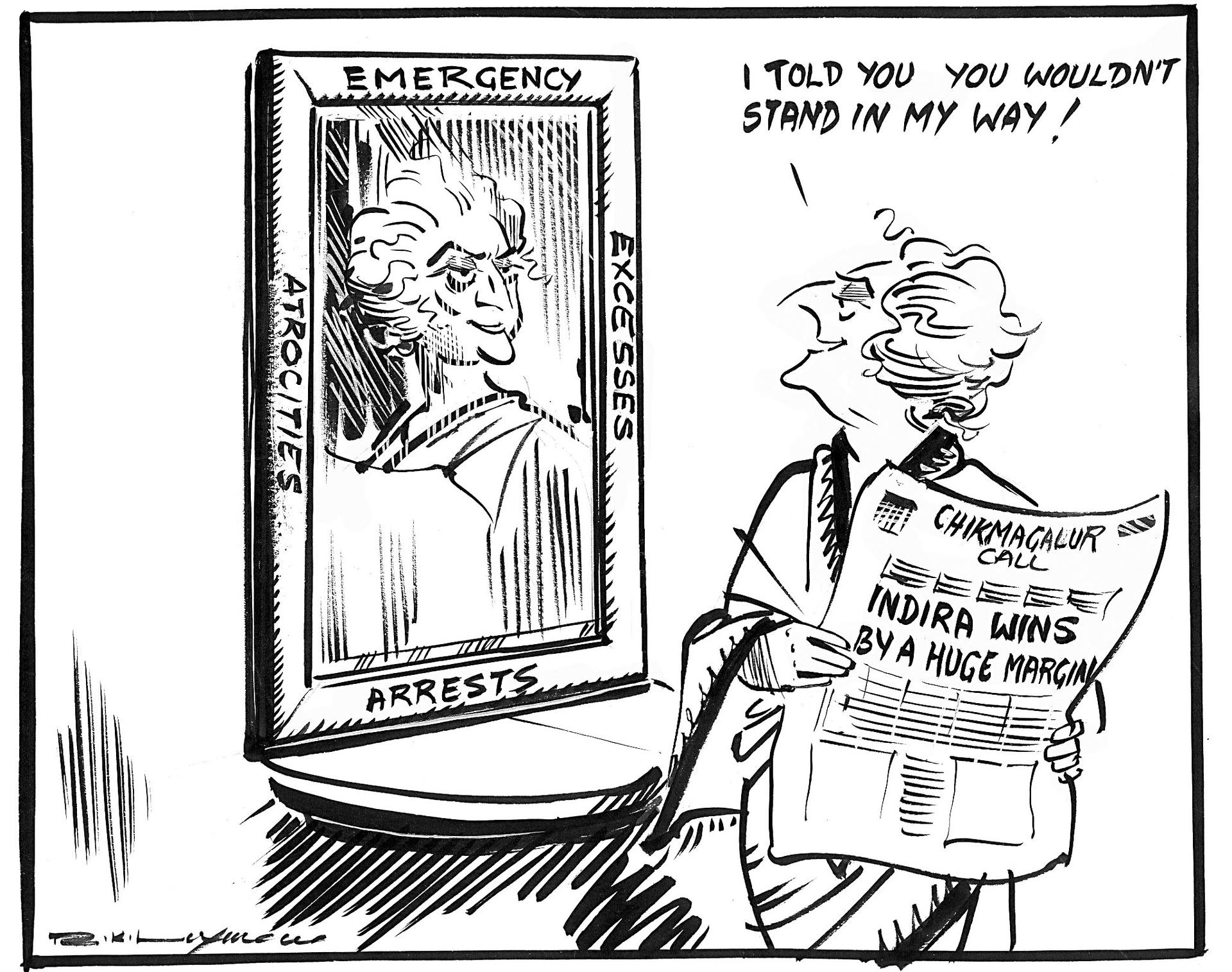

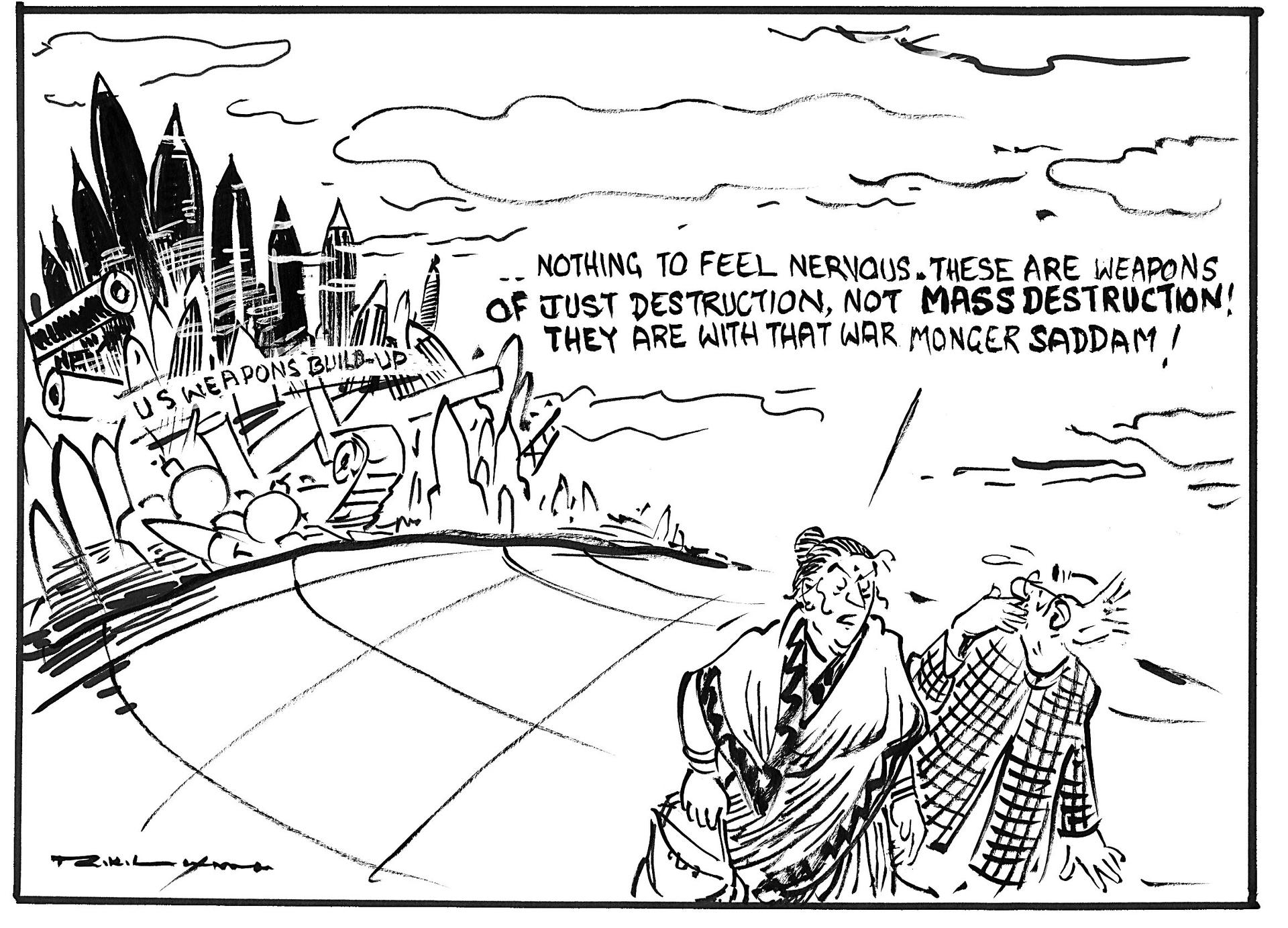

Still, many of Laxman's political cartoons did not include The Common Man. These were larger cartoons addressing national and international politics. Indira Gandhi became a major focus throughout the 1970s. The watershed period was during India's Emergency from 1975 until 1977.

During that time, Indira Gandhi's government shut down political opponents, suspended civil rights and censored any criticicism … of Gandhi. That included some of Laxman's cartoons.

The 21 months of "The Emergency" changed Laxman and he remained critical of Gandhi. He remained so through her second stint as prime minister starting in 1980 until her assassination in 1984.

"He was at his creative peak, I think, after the Emergency," Khanduri says. "He realized that the kind of politics that the Emergency brought to us was possible within a democratic setup. So suddenly the evil wasn't necessarily the colonial government that left us in 1947, but a new kind of issue within democracy and that was Emergency."

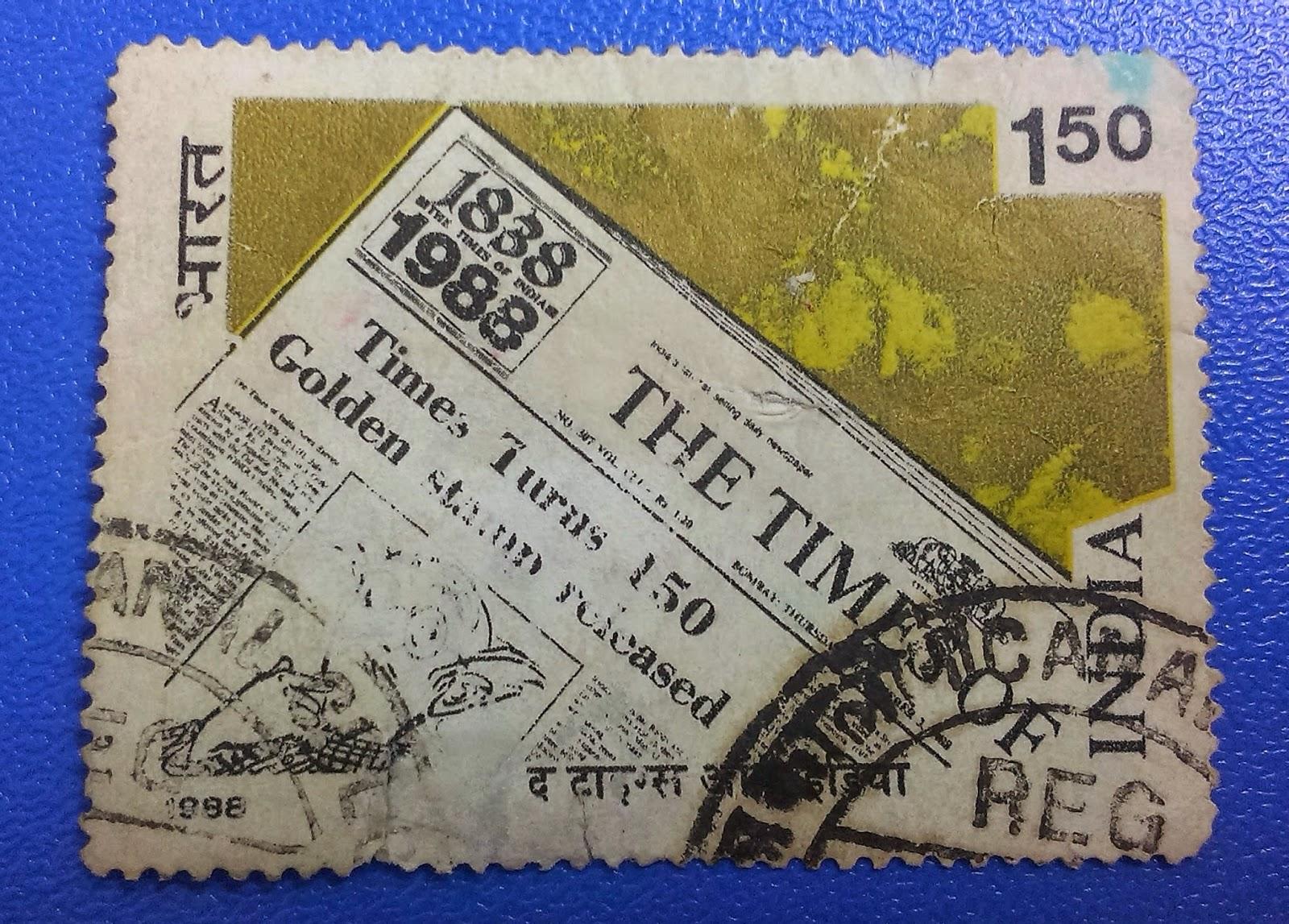

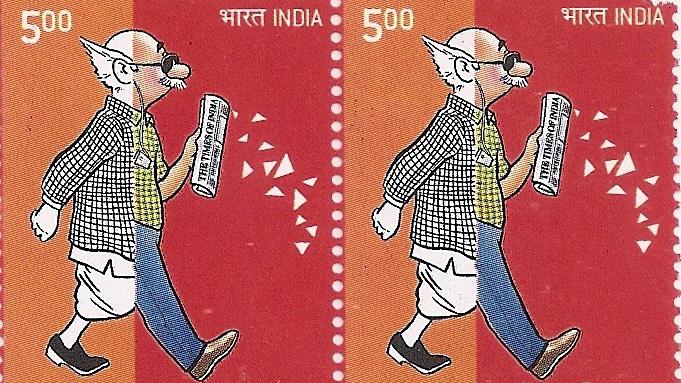

Over the years, Laxman's "Common Man" became the most recognized feature in The Times of India, the largest-circulating English language newspaper in the world. In 1988, the Indian Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp noting the newspaper's 150th anniversary, using the image of The Common Man. The Indian Postal Service repeated the gesture in 2013 for the newspaper's 175th anniversary.

There's a bronze statue of The Common Man in Pune, India, and another facing the sea in Mumbai.

As India's economy roared along in the 2000s, a new Indian budget airline asked for and received Laxman's permission to use The Common Man character as its brand ambassador. The idea was that even The Common Man could afford a ticket on the now defunct Air Deccan. "I think that's what interested Laxman," says Khanduri. "It complemented his preoccupation with the perspective of the Common Man."

In recent years, there was even a Indian TV sitcom based on Laxman's 'Common Man'.

Through it all, Laxman has led both a very public and very private life. He's been interviewed countless times in the Indian media and been feted with numerous awards, yet he's also very private. Former colleagues at The Times of India describe him as prickly, tempermental, unwilling to be edited, and someone who didn't suffer fools gladly. Khanduri had heard all the stories about Laxman, so she was a bit timid when he finally granted her an interview.

"There are all sorts of stories about Laxman being very impatient. But Laxman and his wife were very welcoming," Khanduri says. In 2004, Laxman was still recovering from a stroke and Khanduri's was the first interview he'd given since being ill.

He showed her around his home, including his many drawings of crows, his favorite animal. "I had a very pleasant conversation with him and his wife about his work." When she interviewed him again a few years later, the same: "He did shatter this myth of a very imposing and impatient individual and actually was quite the opposite."

"He's a chronicler of Indian politics. [His cartoons] repeat his complaint about the problems with democracy, the pitfalls of development and the social inequity that has remained, despite half a century of democracy. He is chronicling political change while at the same time returning our attention to the fact that not much has changed and why might that be."

Laxman believes steadfastly that that's a question worth asking. For him, having the right to criticize and exercising that right is as vital to the health of the world's largest democracy as anything. If he's cranky and a big complainer, so be it. As Laxman has written, "Ceaseless public criticism is the best guarantee that the liberty of the individual as well as of the nation will be preserved"

In a 2002 interview on the BBC program Face to Face, Laxman speaks with host Karan Thapar about his childhood, long career, and how he came up with The Common Man character.