Youth unfurl a giant Ukrainian flag as part of celebrations to mark Constitution Day on the Potemkin Stairs in Odessa.

America is the land of immigrants, yes. But what about those potential immigrants who didn't come?

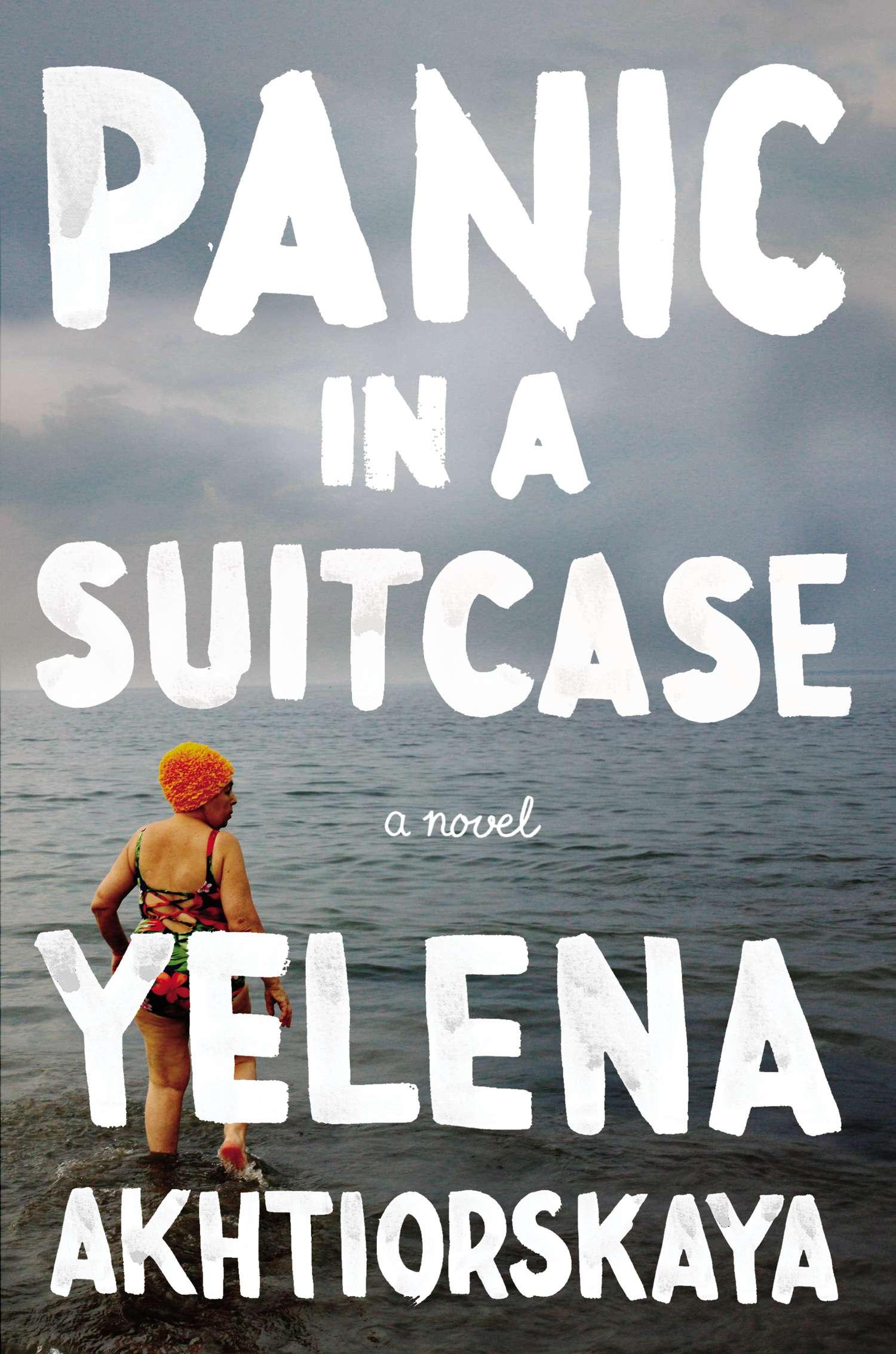

That theme is tenderly explored in Yelena Akhtiorskaya's debut novel, Panic in a Suitcase. The action unfolds in two locales: the Ukrainian city of Odessa and the streets of Brighton Beach in New York, where Akhtiorskaya grew up. The Ukrainian-born characters, who've put down roots in America, desperately want those left behind to join them on the other side of the Atlantic.

For the 29-year-old Akhtiorskaya, it's a scenario that hits close to home. She was born in Ukraine, but left with some of her immediate family to come to America at age seven. The characters in her novel are fictitious, but Akhtiorskaya says some are inspired by the people she left behind.

"Half of our family is still in Odessa — my uncle, my aunt, my cousins who are very close to us," Akhtiorskaya says. "We speak to them basically every single day."

Her uncle who remained in Odessa, Boris Khersonsky, provided a spark for her novel. Khersonsky is a psychiatrist and poet. "He is one of the most brilliant people I know, maybe one of the most brilliant people in the universe," she gushes.

Khersonsky, like the poet Pasha in Panic in a Suitcase, decided to stay back in Odessa rather than start a new life in the United States. "I think the fact that I was thinking so long about my uncle's situation … inspired me to write this book," Akhtiorskaya says.

What does Khersonsky think of his niece's novel? With self-deprecating charm, he argues that Akhtiorskaya had "many reasons" to portray those who stayed behind in Ukraine as somewhat "dysfunctional."

"All people who have practical skills, they would emigrate for sure," Khersonsky says.

Yet it's those who tried to recreate their Ukrainian lives in Brighton Beach that are the more limited characters in her novel. She is less enthralled with "the people who immigrated to America, but then chose not to actually integrate into a new country but to set up a little neighborhood."

Yet it's those who tried to recreate their Ukrainian lives in Brighton Beach that are the more limited characters in her novel. She is less enthralled with "the people who immigrated to America, but then chose not to actually integrate into a new country but to set up a little neighborhood."

That self-imposed cultural isolation, she thinks, is "heartbreaking on the one hand, but also really sad on the other … You just set up a little photocopy of the city you left behind, even though you went to so much trouble to leave the old city."

In contrast, she says, "just not going across the Atlantic Ocean, but staying in your city, can be an act — a very active act."

The story you just read is not locked behind a paywall because listeners and readers like you generously support our nonprofit newsroom. If you’ve been thinking about making a donation, this is the best time to do it. Your support will get our fundraiser off to a solid start and help keep our newsroom on strong footing. If you believe in our work, will you give today? We need your help now more than ever!