The Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, saying farewell to his German counterpart, Joachim von Ribbentrop (right), after a visit to Berlin during the Nazi-Soviet alliance that lasted from 1939 to 1941.

With the stroke of a pen 75 years ago, two men changed the world and sealed the fate of millions.

Those two men were the foreign minister of Nazi Germany, Joachim von Ribbentrop, and his Soviet counterpart, Vyacheslav Molotov. On August 23, 1939, they signed a non-aggression pact, promising not to interfere in case the other went to war.

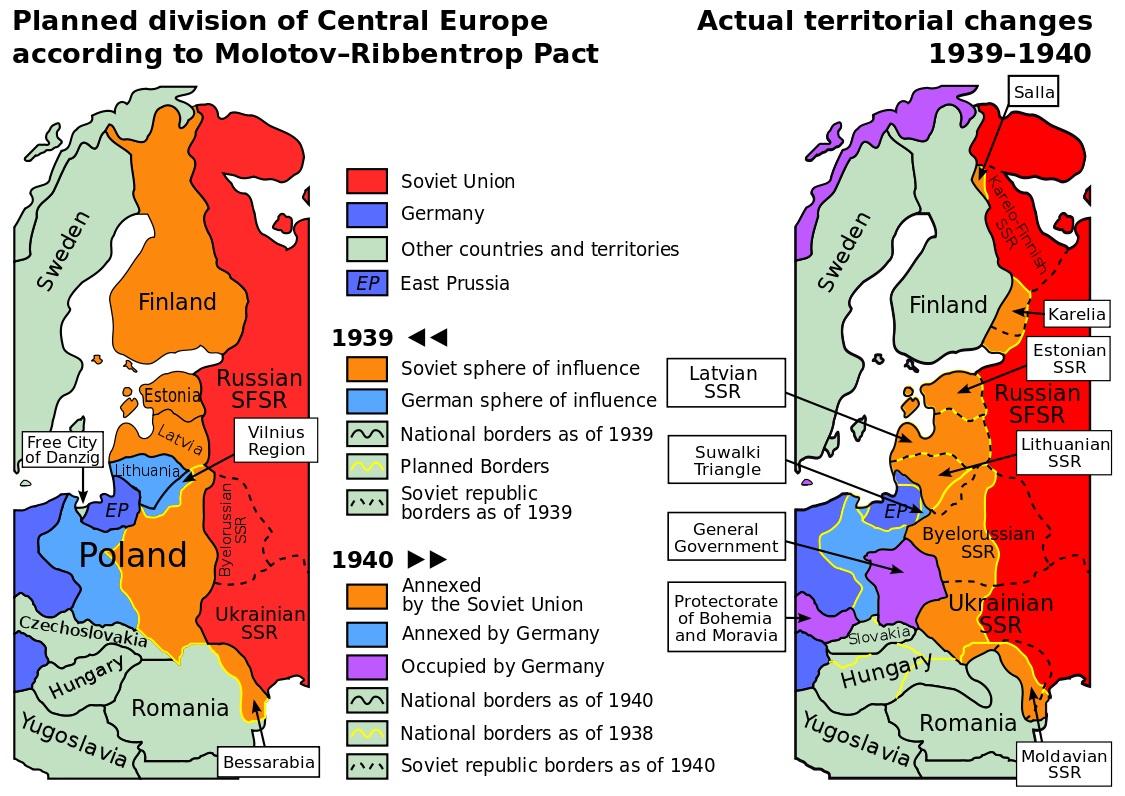

That public announcement was shocking enough: The two totalitarian states had been at loggerheads for years. But they also signed a second, secret agreement that carved up eastern Europe between them. Those world-changing deals are the subject of “Devils’ Alliance: Hitler’s Pact With Stalin, 1939-1941,” a book by historian Roger Moorhouse that’s due out this fall.

“In fact, the Nazi-Soviet Pact as the kick-off for World War II is probably the most surprising scenario that anyone could have imagined,” Moorhouse says. “That’s how you have to view it from the perspective of August 1939. The world was absolutely dumbstruck by this deal.”

Those twin agreements did in fact set the stage for the start of World War II. Within days of signing the pacts, now confident that the Soviets would not oppose him, Hitler invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany, and the war was underway.

A couple of weeks later, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east to grab its share of the spoils. In 1940 it followed up by occupying Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Romanian province of Bessarabia. Britain and France protested, but with their forces already taking on Germany, they couldn’t afford to fight Stalin as well.

For a time, the pact worked well — and showed how similar the two states really were.

In the areas of eastern Europe that they did occupy, the Nazis and Soviets set up occupation zones. Moorhouse says they governed in remarkably similar ways, targeting remarkably similar groups of people. Army officers and officials of the old regimes, intellectuals, priests and community leaders were detained en masse. Thousands were executed or deported to gulags and concentration camps.

The Nazis obviously also targeted Jews, but not many people know that many Jews fled Stalin’s control as well — even seeking sanctuary in Nazi areas. In his book, Moorhouse writes about a moment in which two trainloads of refugees going opposite ways met at a border. They were equally astonished that anyone should want to head in the other direction.

But indeed, both Moscow and Berlin indulged in massive population transfers, each trying to recreate eastern Europe in their preferred image. Thousands of ethnic Germans were moved from the Soviet zones to the German ones, while thousands of Poles were deported from areas now designated “German.” Still others were shipped off as slave laborers to Germany proper. Many people simply moved of their own accord to escape the new states where they were denied basic rights, and some of them eventually came to America.

Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union also cooperated closely economically during their alliance after 1939. Soviet raw materials allowed the Germans to mitigate the worst effects of the British naval blockade, while the Soviets benefitted from German tools and finished goods.

But the Nazi-Soviet pact didn’t last. In late 1939, the Soviets also tried to invade Finland. The Finns refused to roll over. Despite being tremendously outnumbered and outgunned, they improvised a defense and made the best of the terrain and the ferocious winter weather.

One innovation of that campaign was the gasoline bomb, designed for use against the air intake ducts on Soviet tanks. Molotov, the Soviet foreign minister, had called the Russian invasion a “humanitarian” move; Soviet propaganda even claimed that bombs dropped by Soviet planes were food aid. In a sarcastic tribute, the Finns christened their homemade weapons “Molotov cocktails,” joking that they should have drinks along with the Soviet-provided “meals.” In the end, the Soviets suffered a brutal loss in the “Winter War” with the Finns.

The Germans were astonished at how badly the Soviets performed in the Winter War, a performance that made them believe they could turn on Stalin before finishing off the stubborn Brits in the west. In June 1941, Hitler attacked. Moorhouse and other historians say that Stalin was stunned by the invasion and refused to accept that the news was true, leading to disastrous losses by the Red Army in the early days of the war.

Once the Soviet Union recovered and defeated the Nazis, Moscow re-wrote history. The Nazi-Soviet Pact morphed from a delusion to a clever way to buy time, which allowed the Soviet Union to re-arm. Britain and America also tended to airbrush the Nazi-Soviet pact out of mainstream history, afraid that it would damage the popular narrative of the “Grand Alliance” that beat the Nazis.

And that’s only the public half of the alliance: the existence of the secret protocol was officially denied by the Soviet Union until its dying days in 1989.