One woman traveled the world for 10 years to find the oldest living things on Earth

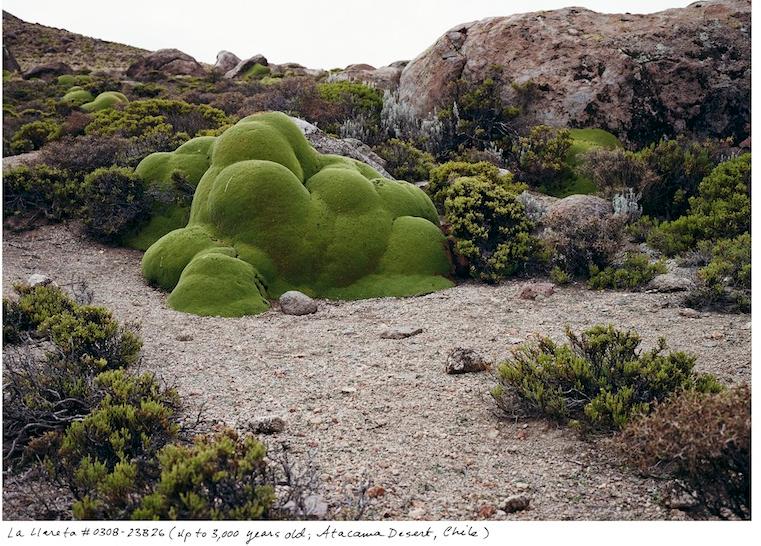

The 3000-year-old Llareta lives in the Atacama desert of Chile.

One of the oldest living things on Earth is a giant plant that grows almost completely underground.

It’s called the underground forest. It's more than 13,000 year old and is one of the many ancient plants and organisms documented by photographer and artist Rachel Sussman in her new book, The Oldest Living Things in the World.

Sussman travelled the world for almost 10 years, gathering photographs for her book. In the process, she learned a lot about biology, botany, history — and the nature of time itself.

Sussman had wanted to include a 3500-year-old tree in Florida in her book, but the tree was accidentally burned to the ground by a couple of kids who thought its hollow trunk would be a cool place to do some meth. It was a life-altering experience for her. Sussman had visited the tree in 2007, but didn’t like her photographs. She meant to go back, but by the next time she could make the trip, the tree was gone.

“You get a false sense of the permanence of these organisms,” she says. “If it's been there for 3500 years, why isn’t it going to be there for 3500 and 5? But it wasn't.”

Sussman says her book was a two-part journey. “One was an actual, literal journey and one was a more conceptual, artistic, creative journey,” she says.

Before setting out on these twin journeys, Sussman had to make a couple of important decisions. First, she had to decide, How old is old?

Sussman chose 2000 years as the minimum age for her subjects. “I really wanted to put both human timekeeping and human lifespans into perspective,” she says, “because they are both so shallow.”

Next, how to decide what is a continuously living entity?

“This is one of those instances where it was wonderful for me to come at this an artist,” Sussman says. “I got to create the parameters in which I was working.”

She decided that anything genetically the same now as it had always been — that is, no new genetic material had ever been introduced — was a continuously living organism , for the purposes of her project. This approach had certain advantages.

“I was able to bring together the bacteria, the clonal seagrass, the clonal aspen trees in Utah — things that you wouldn't necessarily normally look at together,” she explains.

In this respect, her approach was unique: though scientists in many disciplines study aspects of longevity, there is no single area in the sciences that deals with longevity across species.

And the last question: Where to begin? “I had to figure out what I was looking for before I could look for it,” she says. “It's fairly easy to find an old tree list, but there are all these esoteric organisms that I would never have even known to look for.”

Unsurprisingly, she started with Google searches. “If this had been pre-Internet, I would just be scratching the surface now,” Sussman admits.

It turns out that the oldest living things in the world are mostly plants, but Sussman also documented fungus, bacteria and even animals, which was her biggest surprise. For example: coral.

“Corals are actually animals, and I just hadn't really thought about that,” she explains. “I had run into a biologist who’d been vacationing in Tobago and he said, ‘There's this 2000 year-old Brain Coral that lives in Tobago. You should go photograph it.’

Sussman had to learn to scuba dive first, but she went and got her photograph.

Another equally remarkable organism Sussman documents in her book demonstrates the length and breadth of her travels: The Llareta grows in an area of the Atacama Desert in Chile. Parts of the Atacama Desert have not seen a single drop of rain since record-keeping began — some scientists estimate as long 400 years. The area where the Llareta grows is about 15,000 feet up in the mountains. Sussman says you could easily mistake the region for another planet.

As for the plant itself: “Most people mistake the Llareta for moss growing over rocks, because the shape is so strange,” she says. “You would never conceive that this is actually a shrub that is made up of thousands of branches packed really tightly together. At the end of each branch is a tiny cluster of bright green leaves.”

The result is a bulbous shape that's been described as "topiary on steroids."

Of course, the question Sussman must inevitably answer is: "So, what is the oldest living thing in the world?"

The oldest known living thing, she answers, is the "Siberian bacteria." It is between 400,000 and 600,000 years old.

“It was discovered by planetary scientists who were looking for clues to life on other planets,” Sussman explains. “They visited Siberia, one of the harshest places on earth, and they took a core sample of the permafrost. They discovered that this bacteria was doing DNA repair below freezing temperatures. This means that the organism is not dormant, but has been living and growing for what they estimate to be about half a million years.”

What accounts for such longevity? And why the enormous differences across species?

According to Carl Zimmer, a science journalist and New York Times columnist who wrote an essay for Sussman's book, biologists still don’t have a ‘grand unified theory’ explaining the longevity of certain organisms. Nevertheless, Zimmer says, scientists have identified certain ‘molecular tricks’ some of these species use that seem to help them live a long time.

“It does seem like things that live a long time are really good at repairing themselves,” he explains. “As we get older a lot of what’s happening is basically just damage to our molecular equipment — the skin becomes less elastic, muscle becomes weaker and so on. But there are animals and plants that actually are really good at repairing these things — which raises the question, ‘Why don't we all get good at repairing our tissues?’”

Zimmer points out that much of research into animal longevity is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Biomedical researchers want a better understanding of the secrets of longevity ti see if any answers they find might be applied to humans.

Ironically, humans themselves are the greatest danger to many of the world’s ancient living things. So another question inevitably arises wherever Sussman travels:"What are the threats from climate change to the organisms she has documented in her book?"

The better question, Sussman responds, is: "Are any of them not threatened by climate change?"

“The image on the front of the book is essentially a portrait of climate change,” she says. “It is a spruce that … lives in Sweden. It’s 9550 years old. For 9500 of those years it was just a scraggly mass of branches pretty close to ground level, at about the snow line. But what happened in the last fifty years is a new stem in the center shot up. It's directly an effect of the change of the climate zone on the top of this plateau. It got warmer.”

If that seems a bit unsettling, Carl Zimmer provides some small comfort. The fact is, he notes, if all life were somehow wiped off the Earth, there are millions of ancient, dormant bacteria lurking on the ocean floor that would probably repopulate the planet.

And then we could all start over again.

This story is based on an interview that originally aired on PRI's Science Friday.

One of the oldest living things on Earth is a giant plant that grows almost completely underground.

It’s called the underground forest. It's more than 13,000 year old and is one of the many ancient plants and organisms documented by photographer and artist Rachel Sussman in her new book, The Oldest Living Things in the World.

Sussman travelled the world for almost 10 years, gathering photographs for her book. In the process, she learned a lot about biology, botany, history — and the nature of time itself.

Sussman had wanted to include a 3500-year-old tree in Florida in her book, but the tree was accidentally burned to the ground by a couple of kids who thought its hollow trunk would be a cool place to do some meth. It was a life-altering experience for her. Sussman had visited the tree in 2007, but didn’t like her photographs. She meant to go back, but by the next time she could make the trip, the tree was gone.

“You get a false sense of the permanence of these organisms,” she says. “If it's been there for 3500 years, why isn’t it going to be there for 3500 and 5? But it wasn't.”

Sussman says her book was a two-part journey. “One was an actual, literal journey and one was a more conceptual, artistic, creative journey,” she says.

Before setting out on these twin journeys, Sussman had to make a couple of important decisions. First, she had to decide, How old is old?

Sussman chose 2000 years as the minimum age for her subjects. “I really wanted to put both human timekeeping and human lifespans into perspective,” she says, “because they are both so shallow.”

Next, how to decide what is a continuously living entity?

“This is one of those instances where it was wonderful for me to come at this an artist,” Sussman says. “I got to create the parameters in which I was working.”

She decided that anything genetically the same now as it had always been — that is, no new genetic material had ever been introduced — was a continuously living organism , for the purposes of her project. This approach had certain advantages.

“I was able to bring together the bacteria, the clonal seagrass, the clonal aspen trees in Utah — things that you wouldn't necessarily normally look at together,” she explains.

In this respect, her approach was unique: though scientists in many disciplines study aspects of longevity, there is no single area in the sciences that deals with longevity across species.

And the last question: Where to begin? “I had to figure out what I was looking for before I could look for it,” she says. “It's fairly easy to find an old tree list, but there are all these esoteric organisms that I would never have even known to look for.”

Unsurprisingly, she started with Google searches. “If this had been pre-Internet, I would just be scratching the surface now,” Sussman admits.

It turns out that the oldest living things in the world are mostly plants, but Sussman also documented fungus, bacteria and even animals, which was her biggest surprise. For example: coral.

“Corals are actually animals, and I just hadn't really thought about that,” she explains. “I had run into a biologist who’d been vacationing in Tobago and he said, ‘There's this 2000 year-old Brain Coral that lives in Tobago. You should go photograph it.’

Sussman had to learn to scuba dive first, but she went and got her photograph.

Another equally remarkable organism Sussman documents in her book demonstrates the length and breadth of her travels: The Llareta grows in an area of the Atacama Desert in Chile. Parts of the Atacama Desert have not seen a single drop of rain since record-keeping began — some scientists estimate as long 400 years. The area where the Llareta grows is about 15,000 feet up in the mountains. Sussman says you could easily mistake the region for another planet.

As for the plant itself: “Most people mistake the Llareta for moss growing over rocks, because the shape is so strange,” she says. “You would never conceive that this is actually a shrub that is made up of thousands of branches packed really tightly together. At the end of each branch is a tiny cluster of bright green leaves.”

The result is a bulbous shape that's been described as "topiary on steroids."

Of course, the question Sussman must inevitably answer is: "So, what is the oldest living thing in the world?"

The oldest known living thing, she answers, is the "Siberian bacteria." It is between 400,000 and 600,000 years old.

“It was discovered by planetary scientists who were looking for clues to life on other planets,” Sussman explains. “They visited Siberia, one of the harshest places on earth, and they took a core sample of the permafrost. They discovered that this bacteria was doing DNA repair below freezing temperatures. This means that the organism is not dormant, but has been living and growing for what they estimate to be about half a million years.”

What accounts for such longevity? And why the enormous differences across species?

According to Carl Zimmer, a science journalist and New York Times columnist who wrote an essay for Sussman's book, biologists still don’t have a ‘grand unified theory’ explaining the longevity of certain organisms. Nevertheless, Zimmer says, scientists have identified certain ‘molecular tricks’ some of these species use that seem to help them live a long time.

“It does seem like things that live a long time are really good at repairing themselves,” he explains. “As we get older a lot of what’s happening is basically just damage to our molecular equipment — the skin becomes less elastic, muscle becomes weaker and so on. But there are animals and plants that actually are really good at repairing these things — which raises the question, ‘Why don't we all get good at repairing our tissues?’”

Zimmer points out that much of research into animal longevity is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Biomedical researchers want a better understanding of the secrets of longevity ti see if any answers they find might be applied to humans.

Ironically, humans themselves are the greatest danger to many of the world’s ancient living things. So another question inevitably arises wherever Sussman travels:"What are the threats from climate change to the organisms she has documented in her book?"

The better question, Sussman responds, is: "Are any of them not threatened by climate change?"

“The image on the front of the book is essentially a portrait of climate change,” she says. “It is a spruce that … lives in Sweden. It’s 9550 years old. For 9500 of those years it was just a scraggly mass of branches pretty close to ground level, at about the snow line. But what happened in the last fifty years is a new stem in the center shot up. It's directly an effect of the change of the climate zone on the top of this plateau. It got warmer.”

If that seems a bit unsettling, Carl Zimmer provides some small comfort. The fact is, he notes, if all life were somehow wiped off the Earth, there are millions of ancient, dormant bacteria lurking on the ocean floor that would probably repopulate the planet.

And then we could all start over again.

This story is based on an interview that originally aired on PRI's Science Friday.