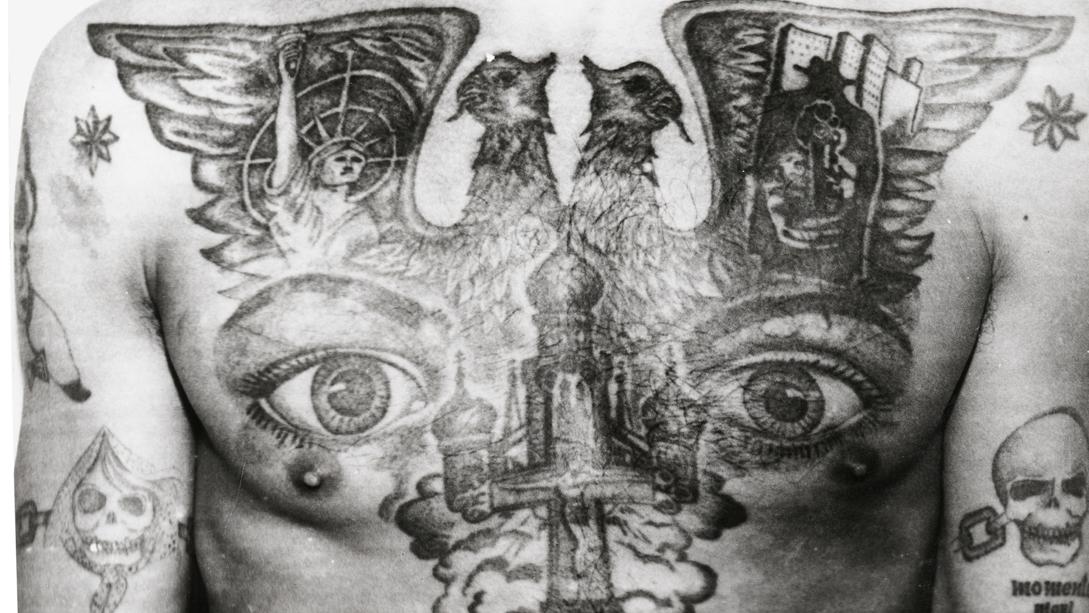

The eyes tattooed on this Soviet prisoner's chest signify "I can see everything" and "I am watching," the powerful tattoo of a criminal "overseer." The eight-pointed stars tattooed on the shoulders mark the bearer as an "authoritative’" thief.

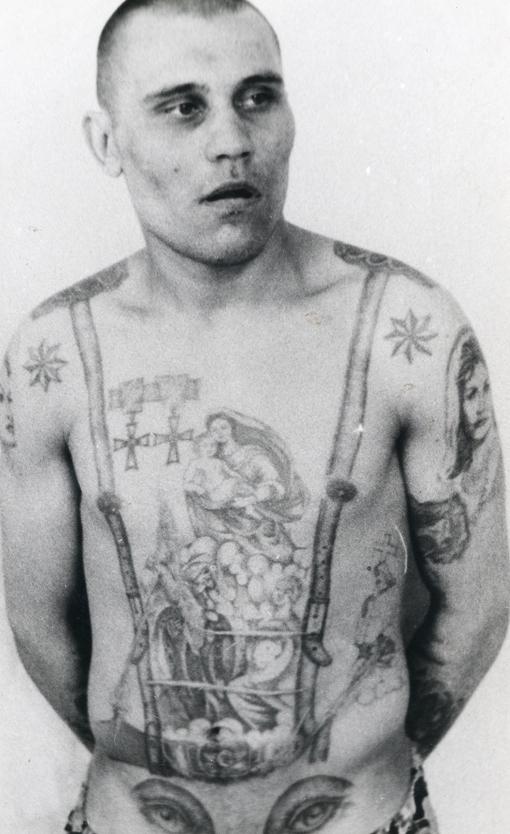

Imagine your resume was actually tattooed on your body; all your achievements — or lack thereof — explained in pictures for everyone to see. If you were a Russian prisoner during most of the 20th Century, you didn't have to imagine: your skin said a lot about you.

The art of the prison tattoo evolved into a language of its own during the Soviet era, one almost incomprehensible to anyone but inmates and a handful of experts within the prison system. The archive of one of these experts, criminologist Arkady Bronnikov, was once used to help Russian cops identify criminals and sometimes their victims.

Bronnikov's work is the subject of a new book titled "The Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files." “[Bronnikov’s] idea was that he would build up a library of images, and from that library he would be able to gague the meaning and the history of each criminal," says Damon Murray, co-founder of Fuel Publishing, which produced the book.

By the way, we’re not talking about political prisoners — the key word here is “criminal."

“The interesting thing about these works, is that they give us a unique insight into that world,” Murray says, “how that world is constructed, how people get their status within that world and how people were lowered.”

Prison tattoo artists were known as “prickers.” They used jerry-rigged razors and ink made from a cocktail of ashes, urine and scorched rubber. Even though they were illegal — and sometimes fatal — Murray says tattoos were so desirable that, when word got out about talented prickers, criminals would even try and get themselves transferred to those particular prisons.

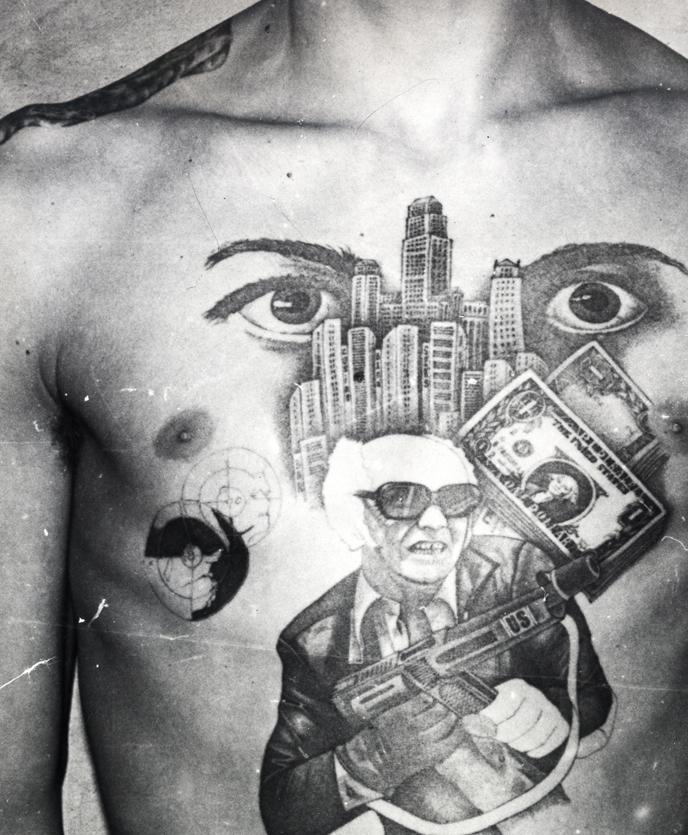

The tattoos became a covert form of communication, part rap sheet and part confessional. To decode them, you had to practice a kind of reverse logic:

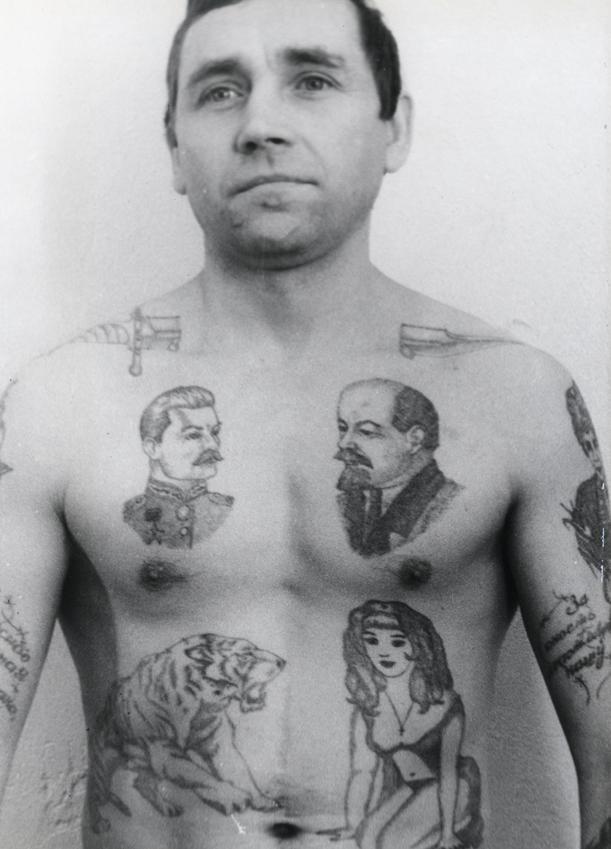

“Symbols of churches and crosses don’t represent the person’s belief in God, they represent the kind of thieves' cross,” Murray expolains. “Or the domes of the churches represent sentences served.”

The tattoos also served as badges, establishing a prisoner’s status in the criminal hierarchy. “If someone has eyes on their chest, then they’re a powerful criminal who’s looking out and overseeing all the other criminals, so they’re in a position of power," Murray says.

They could also convey personal information — “If the eyes are tattooed just above the groin, that makes them a homosexual criminal” — or even serve as a vehicle for revenge.

Once, while I was traveling in Russia, I caught a lift with a guy who had spent 14 years in prison for killing a man. He was covered in tattoos — yeah, that should have been a clue — but I had no idea what they meant. So I asked Damon Murray for a quick primer: When should you run?

“Anything with a skull and a knife going through it generally means they’re a murderer in some shape or form,” Murray says with a laugh, then adds: “Sounds pretty obvious, but if they’ve got a dagger going through their neck, that means that they’re a murderer or a killer."

At least, that used to be the case. “People are still being tattooed, but it’s not in the same way," Murray says. "It kind of started to die out in the late '80s and early '90s, when drugs became massive within the Russian prison system. And that meant that people could buy their tattoos, whereas previously they had to earn their tattoos.”

And if they didn’t earn them, they’d be handed a brick or a piece of glass and told to erase them.

Money stripped Russian prison tattoos of their significance, and so has the popularity of tattooing in general. Twenty-five years ago in Russia, having a lot of tattoos pretty much defined you as a criminal. Whereas today — that young Russian guy with a tattoo of a knife through his neck?

Maybe he just, you know, really likes knives.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?