Pidgin, patois, slang, dialect, creole — English has more forms than you might expect

The phrase ‘Wha gwan’ (whaa gwaan) means ‘what’s going on’ in Jamaican Patois. The spelling varies but the meaning does not change.

There are probably as many terms for different kinds of English vernacular as there are vernaculars themselves: pidgin, patois, slang, creole dialect and so on.

But while we usually think of the vernaculars as oral versions of the English language, they're making their way into the written word as well.

“There's a really interesting paradox going on, where you're taking something that's constantly changing — and that people don't expect to see written down — and you're making it codified and setting it down for a wider audience," says Dohra Ahmad, editor of an anthology of vernacular literature called "Rotten English."

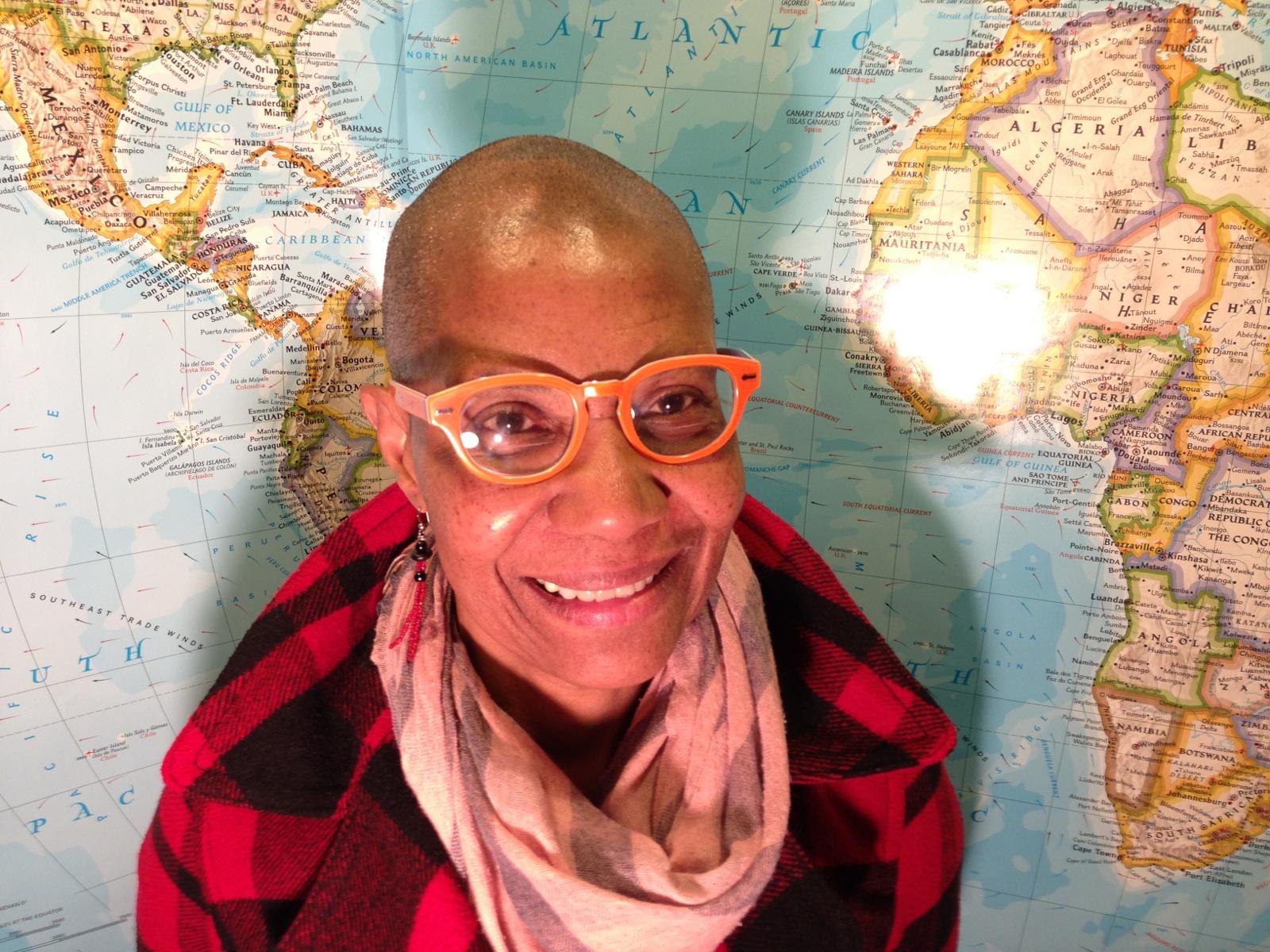

M. NourbeSe Philip, one of the authors included in the anthology, speaks and writes Trinidadian Creole but points out that the process of getting the language on the page is much the same as writing in Standard English.

“You can’t write it exactly as the person speaks it," she says. "You have to put it through a certain process that conveys the impression that it is being said in the dialect."

She writes both in dialect and in standard English, with her characters switching back and forth between the Englishes.

“As people from the Caribbean, we inhabit a spectrum of language, and you actually hear it when you go into the cultures," Philp says. "You can hear somebody code-switching. You might start off saying something in Standard English and midway switch into the dialect or the vernacular."

Code-switching between patois and standard English can be traced back centuries, to when English and other European languages were brought to the Caribbean, Philip says. But it hasn't always gotten the respect its pedigree deserves.

“When I grew up [the vernacular] was called ‘bad English,’" she remembers.

Philip wants to be able to use all the resources of the language. “I think young people need to know that when they go for jobs and so on that they have to be able to articulate in a certain way, the Standard English,” she says, arguing they should also be taught to appreciate the vernacular.

“There’s so much energy in it, there’s so much life in it," Philip says. "If you really can work it on the page, I think it’s incredibly vibrant."

People often asked who has the right to use a particular vernacular, but Philip is quick to dismiss the question of rules.

“Let’s take the Caribbean: you have Europeans, you have South Asians, you have Africans — people from all backgrounds," she says. "If they grow up speaking the language and being in touch with the language and can use it, then the reviewer or the people reading [the work] to assess it can't say, ‘This doesn’t work. This doesn’t seem authentic.’”

Philip also says being proficient and authentic has nothing to do with the color of one’s skin or origins. She remembers watching a white Canadian comedian in Toronto do a set in Jamaican patois. It was a language that he had picked up from living in a largely Jamaican neighborhood.

“He picked up patois and he had us in stitches," she says. "He had the intonation and he had it down and that was fine.”

While there may not be rules as to who can write or speak or joke in the vernacular, the language is part of people’s cultural heritage. Jamaican patois, for example, is a rich resource and part of the Jamaican culture. “I wouldn’t say it belongs to them, I’d say they own it,” Philip says.

“And remember, I have to say that this is a legacy that comes from a deep historical trauma of people not being allowed to use their own languages and then weren’t being taught the best way to use those European languages," Philip says. "I think it’s a marvelous resource that those ancestors were able to wrest out of something that was so tragic."