In Other Words

A weekly series of interviews about how translation has changed the English speaking world. <br />Editor: <a href="http://pri.org/people/patrick-cox">Patrick Cox</a><br />Reporter/Producer: <a href="http://pri.org/people/nina-porzucki">Nina Porzucki</a>

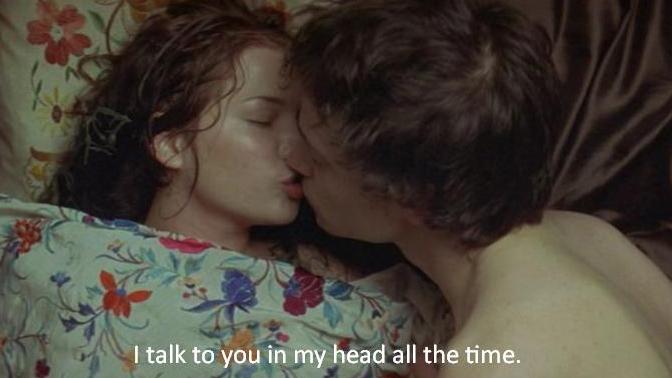

Meet the folks behind the subtitles on your favorite movies and streaming TV shows

Remember the last time you saw a foreign language film? You sat down in the dark, popcorn in hand, and for the next two hours you read all those subtitles. But even if you’ve seen a lot of subtitled movies, you’ve probably never thought of who wrote those fleeting words on the screen?

How did English become the language of science?

It’s Nobel Prize season. While scientists throughout the world will be awarded this prestigious prize, there’s a good chance all of their research was written up in English. Michael Gordin, a professor of the history of science at Princeton, wrote a new book, “Scientific Babel” that explores the intersection of the history of language and science.

How the Nuremberg Trials changed interpretation forever

We take simultaneous interpretation for granted today, watching world leaders at the UN and other organizations listen to speeches being translated in real time. But there was a time not too long ago when even the thought of someone instantly translating speech was impossible.

You are what you eat — and how you translate the menu

Why does an entrée mean a different part of the meal in America and England? How did tea and chai become universal terms? Linguist Dan Jurafsky, author of the new book The Language of Food, talks about how the grammar of food affects us every time we sit down to a meal.

We love fairy tales — maybe we’d love them more if they were translated right

If you think you know the story of Snow White, or Hansel and Gretel or any of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales, think again. You probably know the cleaned-up, Disney versions. Author Adam Gidwitz returns to the blood and gore of the original stories in his retelling of them, while adding his own contemporary comments to help ease the tension for kids.