A Hollywood trick has become a medical innovation

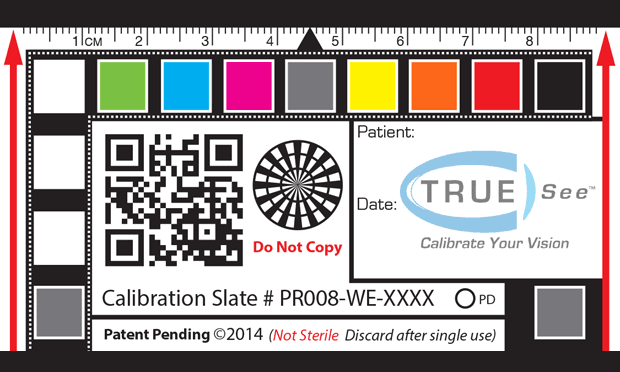

A TRUE-See calibration slate. The device is used to standardize photos of wounds, allowing caregivers to make accurate comparisons and diagnoses.

Dr. Shaun Carpenter admits he has a slightly unusual hobby.

“Some doctors golf,” says Carpenter, a wound care specialist in Louisiana. “My hobby is to make movies.”

But in the process of amateur filmmaking, he has stumbled upon a way to improve medical care.

Several years ago, Carpenter made a short film called Halfway about the friendship of two boys in New Orleans. Carpenter wanted the film to look as good as possible, so he hired a local cinematographer named Francis James. James has worked on major projects like Monster's Ball and HBO's True Blood.

Along the way, the two men got to talking about photography. Photographs are a crucial part of Carpenter’s clinical practice — the medical team uses them to record the size and colors of wounds and changes in the tissue as they heal.

Carpenter told James he was frustrated with the wound photos. "I can't get my nurses to take two pictures that look alike," he said. "Some of the wound pictures were out of focus, they were blurry — the quality was terrible."

James took a look at the medical photos and was astounded by how bad they were: “I looked at what they were doing and I said, ‘Are these the pictures you are using in your medical records?’”

James began working with Carpenter’s team at North Shore Specialty Hospital in Covington, Louisiana. First he set up ajerry-rigged light source on a tall stand, hoping to give the nurses more even, diffused light. The already-overworked nurses looked at him like he was out of his mind.

James quickly realized that controlling the conditions of the photography would be impossible.

"If you take a picture of a wound with three different cameras in exactly the same situation with exactly the same lighting, they all look different," James says.

So he began thinking about the problem from the opposite direction: correcting the images afterward.

Borrowing a solution from the film industry, James developed a slate to be placed next to the wounds in the photos. The slate is marked with with colored squares and a graduated grid, and a simple piece of software uses it to calibrate the colors in the image and save it directly into the patient’s medical record.

Using standardized, color-corrected images means doctors can rely less on judgment calls and written descriptions.

"Each slate has a unique number, so we track everything," James says. "You know where it was created or if it was altered. You have a provenance for every picture."

James and Carpenter called the system TRUE-See.

"TRUE-See allows everything to be accurate, whereas before things could be judgmental," says one of Carpenter's staff nurses. "What I see as the amount of slough in a wound, or bad tissue, or dead tissue — that can be subjective. If three different people have seen that patient and measured a wound in different ways, then how do you know if [the healing process] has stalled or not?"

The TRUE-See system allows the doctors and nurses to accurately graph the progress of a wound. That enables everyone to better answer crucial questions: Is the wound getting better? Is it getting smaller? Do we need to change anything we're doing?

TRUE-See keeps revising the slate based on feedback from caregivers. James noticed that nurses were cutting the slates in half, so he made them shorter. He also saw them putting tape on the back, so he added an adhesive. The process is continuing — they're now on the 24th version.

Carpenter believes the system is a leap forward in caring for wounds. Unlike a lot of medical innovations, however, TRUE-See relies on a new perspective on the problem rather than new technology.

“I always joke that in the film industry we treat everything like it’s life or death,” James says. “If Tom Cruise is waiting on something, it’s life or death. And I looked over at what the nurses and clinicians were doing and I said, ‘How can I make this something you can do? Because you are dealing with life and death. We’re not.’”

Dr. Shaun Carpenter admits he has a slightly unusual hobby.

“Some doctors golf,” says Carpenter, a wound care specialist in Louisiana. “My hobby is to make movies.”

But in the process of amateur filmmaking, he has stumbled upon a way to improve medical care.

Several years ago, Carpenter made a short film called Halfway about the friendship of two boys in New Orleans. Carpenter wanted the film to look as good as possible, so he hired a local cinematographer named Francis James. James has worked on major projects like Monster's Ball and HBO's True Blood.

Along the way, the two men got to talking about photography. Photographs are a crucial part of Carpenter’s clinical practice — the medical team uses them to record the size and colors of wounds and changes in the tissue as they heal.

Carpenter told James he was frustrated with the wound photos. "I can't get my nurses to take two pictures that look alike," he said. "Some of the wound pictures were out of focus, they were blurry — the quality was terrible."

James took a look at the medical photos and was astounded by how bad they were: “I looked at what they were doing and I said, ‘Are these the pictures you are using in your medical records?’”

James began working with Carpenter’s team at North Shore Specialty Hospital in Covington, Louisiana. First he set up ajerry-rigged light source on a tall stand, hoping to give the nurses more even, diffused light. The already-overworked nurses looked at him like he was out of his mind.

James quickly realized that controlling the conditions of the photography would be impossible.

"If you take a picture of a wound with three different cameras in exactly the same situation with exactly the same lighting, they all look different," James says.

So he began thinking about the problem from the opposite direction: correcting the images afterward.

Borrowing a solution from the film industry, James developed a slate to be placed next to the wounds in the photos. The slate is marked with with colored squares and a graduated grid, and a simple piece of software uses it to calibrate the colors in the image and save it directly into the patient’s medical record.

Using standardized, color-corrected images means doctors can rely less on judgment calls and written descriptions.

"Each slate has a unique number, so we track everything," James says. "You know where it was created or if it was altered. You have a provenance for every picture."

James and Carpenter called the system TRUE-See.

"TRUE-See allows everything to be accurate, whereas before things could be judgmental," says one of Carpenter's staff nurses. "What I see as the amount of slough in a wound, or bad tissue, or dead tissue — that can be subjective. If three different people have seen that patient and measured a wound in different ways, then how do you know if [the healing process] has stalled or not?"

The TRUE-See system allows the doctors and nurses to accurately graph the progress of a wound. That enables everyone to better answer crucial questions: Is the wound getting better? Is it getting smaller? Do we need to change anything we're doing?

TRUE-See keeps revising the slate based on feedback from caregivers. James noticed that nurses were cutting the slates in half, so he made them shorter. He also saw them putting tape on the back, so he added an adhesive. The process is continuing — they're now on the 24th version.

Carpenter believes the system is a leap forward in caring for wounds. Unlike a lot of medical innovations, however, TRUE-See relies on a new perspective on the problem rather than new technology.

“I always joke that in the film industry we treat everything like it’s life or death,” James says. “If Tom Cruise is waiting on something, it’s life or death. And I looked over at what the nurses and clinicians were doing and I said, ‘How can I make this something you can do? Because you are dealing with life and death. We’re not.’”

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!