The History and Future of Government-Monastery Relations in a Changing Myanmar

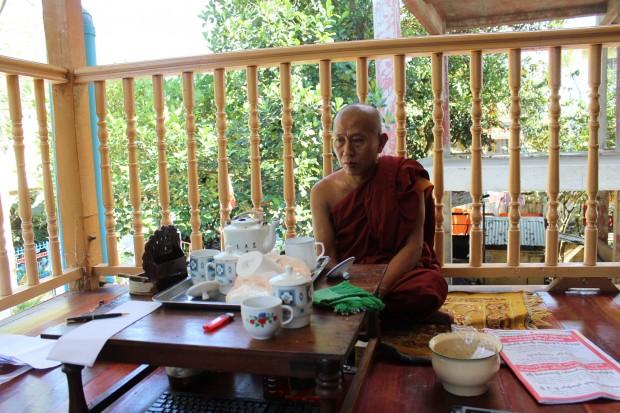

U Indaka, abbot at Yangon’s Maggin Monastery. (Photo: Bruce Wallace)

Hardline Buddhist monks fomenting against Muslims; dozens of monks on the frontlines of ongoing protests against a Chinese-run copper mine-these are the latest reminders of the powerful role Buddhist clergy often play in public life in Myanmar. The activist tradition among monks goes back a ways in the country, also known as Burma. And that has often put them at odds with the government.

As reforms continue to unfold in Myanmar, we wanted to see how the relationship between these two powerful forces might be shifting.

Rebuilding is underway at Maggin Monastery, up a narrow dirt road in a busy Yangon township. It started last spring after Maggin's abbot, U Indaka, got out of prison. He'd been there since 2007"²s Saffron Revolution —a monk-led protest sparked by spiking energy costs. Police locked the monastery after they arrested him. By the time he got out, the building was in ruins.

The monastery has been a haven for activists since the 1980s. Indaka sees it as part of his work as a monk.

"Some people say that monks shouldn't be involved in politics," Indaka says through an interpreter. "But to me this isn't politics. If you want to do politics you can join a party. When the government oppresses people, then monks are oppressed too. Then, making a revolution is the right thing to do."

The tradition of political activism among monks has deep roots in Myanmar. Monks were a force in the country's anti-colonial movement beginning in the 1920s. In recent decades, they repeatedly opposed the military junta that controlled the country until 2011.

The government responded with crackdowns and arrests, but also in more subtle ways. In the early '80s it appointed 47 monks to a "Sangha Council" meant to arbitrate monastic issues. Much of the council's work aimed at keeping activist monks in check.

U Pandavansa is an abbot at another Yangon monastery. He worked with Indaka during the Saffron Revolution, and was also thrown in jail and had his monastery shut.

He shows me a copy of the Sangha Council's 96 regulations-lots of don'ts he says. Chief among them: don't get involved in politics.

But the Buddha and Buddhist scripture already tell us what to do and what not to do, he continues, we don't need the Council to tell us that.

"It's like being controlled by two governments," he says through an interpreter.

U Tilawaka is head monk at another, sprawling Yangon monastery. And he was also jailed… locked up for two-and-a-half years in the early 90s for publicly supporting monks protesting the government. But, in 2004, he accepted a spot on the Sangha Council.

"I joined the council thinking that there were a lot of things I could do for the monasteries. After six years I realized I couldn't make a difference," Tilawaka told me through an interpreter.

He quit the council. He said it mostly seemed concerned with making rules.

Everyone I talked to said they'd seen no signs of the council evolving as reforms take hold in other parts of Myanmar society. In the past year-and-a-half the council has taken action against two high-profile politically active monks.

Thiha Saw is a long-time journalist and editor in Yangon. He echoed what others told me—the goal isn't to get rid of the council, but to cut the ties that bind it to the government.

"The basic issue is about whether it's an independently elected body. The monks association, or whatever you call it—the Sangha Council—should be something that's totally independent from the Ministry of Religion or from the government," Saw says.

But, while the council doesn't seem to be moving away from the government, the government may be moving away from the council.

Juliane Schober , a professor at Arizona State University who has studied the dynamic between Myanmar's monks and its government, says that during the many years that the government was un-elected and the constitution was suspended, leaders derived legitimacy from lavish, public displays of support for Buddhism. These were often mediated by the council.

She's seen a lot less of that recently.

"Now that liberal reforms are underway in all sorts of public arenas, I think it's important for the government to present itself as representing all citizens of Myanmar, including non-Buddhist populations," she says.

For their part, the activist monks will wait and see, and continue to rebuild.