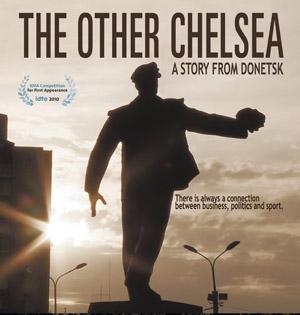

Official movie poster of ‘The Other Chelsea.” (Photo: theotherchelsea.com)

Several European leaders are threatening to boycott the Euro 2012 soccer tournament in Ukraine next month over the alleged abuse of the jailed former prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko. She just ended a hunger strike.

The tournament is one of Europe’s biggest sporting events, and it’s likely to attract tens of thousands of fans. Some of the matches will be held in the city of Donetsk, a coal mining city in eastern Ukraine.

It’s also the setting of an award winning new documentary by a German filmmaker called “The Other Chelsea.” The name is a reference to Donetsk’s professional soccer club, Shakhtar. The film follows a group of coal miners from Donetsk in 2009, the year Shakhtar won the Europa league tournament, a first for a Ukrainian team.

But “The Other Chelsea” isn’t just about soccer. It’s about the other Ukraine, the one that didn’t support the 2004 Orange Revolution, and that still considers Moscow its capital, not Kiev.

Jakob Preuss, the film’s director, got interested in this part of Ukraine after working as an election observer in 2004.

“I was sent to Donetsk probably because I speak Russian,” Preuss said, “and I was deeply impressed by this divide in the country between east and west, orange and blue.”

Preuss’s film shows the country’s starkest divide – between rich and poor. Nowhere is that more apparent than in Donetsk; it’s Ukraine’s Appalachia.

“I have these coal miners who are the losers of the breakdown of the Soviet Union, who live in really horrible conditions, still working in this mine which is really dangerous,” Preuss said.

They’re also fanatically devoted to their soccer team.

“You have this new political elite, the oligarchs, who also go to the stadium, because if you want to become something in Donetsk, you have to be there,” he said.

The oligarchs are up in the VIP box, rubbing shoulders with Ukraine’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov. He owns the club, and never misses a game.

Preuss wasn’t able to get an interview with the reclusive Akhmetov, but he did get to know another Donetsk oligarch, an ambitious young politician named Kolya.

“He’s really representative of this very corrupt, Machiavellian elite,” said Preuss.

Kolya actually has a copy of Machiavelli in his flat, not to mention a picture of Stalin on his office wall. He lives like a prince, despite his small salary as a city councilman.

“Normally people go into business, make a lot of money, and then they go into politics just to protect their wealth and have the immunity and play around with politics to make even more money,” Preuss said.

But Kolya got rich from politics, by steering government contracts to his construction companies.

“All Ukrainian politicians in parliament, on paper they’re not supposed to have businesses, but they’re all millionaires or billionaires,” Preuss said. “This is so normal there that Kolya didn’t even think not to tell me, which shows what a mess this country is in.”

In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Kolya calmly explains the way the political system works in Ukraine.

“In your Europe, the judiciary protects both government and opposition,” Kolya says. “Here, the judiciary only protects the people in power. If you lose the election, you go to jail.”

Like former presidential candidate Yulia Tymoshenko.

“This has been quoted a lot of times in Ukraine,” according to Preuss, “because people couldn’t believe that this guy would say it so bluntly.”

But Kolya’s not the only blunt talker. Preuss introduces us to Stepanovitch, a pit-worker in his late sixties who’s spent his whole life in the mines.

In the film, Stepanovitch says, “I think all these millionaires are thieves and bandits. Our whole system, everyone in power, they’re all criminals.”

Stepanovitch, whose son was killed in a mining accident, thinks life was better back when Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union.

“Even when times were bad,” he says in the film, “at least we stuck together.”

His girlfriend, Valentina, who works in the mine’s front office, agrees.

An irrepressible flirt, she sports an enormous blond beehive and leopard skin outfits, despite her not exactly girlish figure.

Preuss said when Valentina attended the premier of “The Other Chelsea” in Kiev, she received a standing ovation.

In fact, audiences throughout Ukraine – east and west – love this film, perhaps because Jakob Preuss doesn’t just show us the miserable living conditions of the coal miners, but also their warmth, humor and humanity.

“A Ukrainian told me yesterday that for him, post-Soviet people are often like coconuts. They’re a little bit hard on the outside, but they’re soft inside. And Europeans and Americans are like peaches, soft on the outside, but hard on the inside.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?