United Kingdom: Rationing health by cost

Some argue that the goal of medical rationing should be to focus resources where they will offer the greatest health benefit to the greatest number of people.

That is the aim of the UK’s rationing plan. But Britain’s plan is now under fire.

If ever there were a place where the public might embrace the rationing of health care, that place would arguably be Britain.

During World War II and for nine years after, the British government rationed most food items: meat, flour, eggs, sugar. The government also strictly controlled the supply of gasoline, soap, stockings—even the number of buttons on jackets.

Although there was wartime rationing elsewhere, including in the United States, it generally applied to fewer items over fewer years and was quickly forgotten. In Britain, however, rationing became a part of the national identity.

Many older Britons speak of rationing as a great legacy of those wartime and post-war years, when people sacrificed their own interests for the greater good.

After World War II, the British government extended this societal approach to health care. It created the National Health Service, the NHS.

Today, 95 percent of Britons get their care through the government-run program. In order to provide care to everyone, the government says it must place limits on the care it provides. It must ration.

Limits to Care

“We have a limited budget for health care, voted by Parliament every year, and we have to live within our means,” said Michael Rawlins, chairman of a government agency called the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

NICE decides which drugs and other treatments can be prescribed by NHS doctors.

NICE was created in 1999 to clarify the reasons why certain drugs are approved and others are rejected. “In the old days it used to be done in secret, behind closed doors, in smoke-filled rooms,” Rawlins said. “Now it’s explicit. Everybody knows what the rules are.”

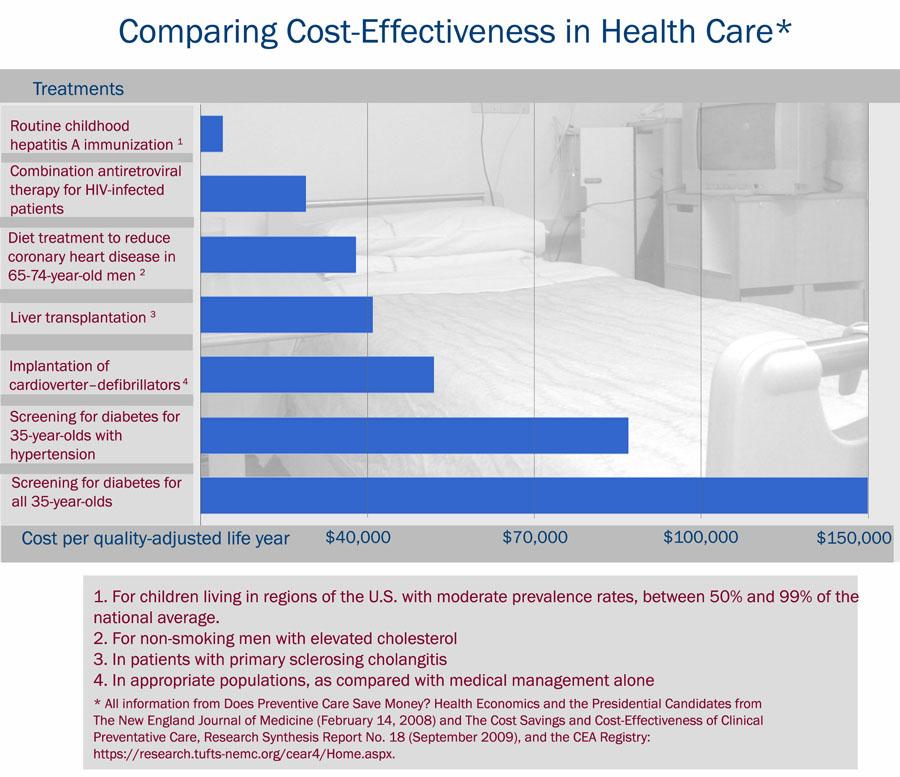

NICE’s rationing decisions start with a basic premise: The government should spend its limited resources on treatments that do the most good for the money. NICE calculates cost-effectiveness with a widely used measure called a quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

In essence, NICE asks these questions: How much does a drug or procedure cost? How much does the treatment extend the average patient’s life? And what is the quality of that life gained?

The calculations are complicated, but imagine that a cancer treatment costs $100,000 and that it extends the life of the average patient by four years. That means the cost of the treatment per year gained is $25,000.

Now imagine that for part of those four years the patient will be in pain and bedridden. NICE might figure the quality of that life at 50 percent of perfect health. Under NICE’s formula, that would make the drug half as cost-effective. In other words, the result would be $50,000 per quality-adjusted year gained.

NICE has set a maximum that it will spend on a treatment: about $47,000 per quality-adjusted year gained.

NICE tends to assume, without always performing calculations, that most common treatments are cost effective—including insulin for diabetes, cholesterol-lowering drugs for heart disease, and kidney transplants.

Instead, NICE analyzes only selected therapies, such as expensive new drugs that may extend life at the end of life. It has calculated that some of the more expensive drugs meant to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s Disease and some cancers fall below the cost-effectiveness threshold. In such cases, NICE says, the NHS shouldn’t pay for the drugs.

NICE chairman Michael Rawlins acknowledged that his agency’s decisions deprive some patients of drugs that may extend their lives by several months or more.

“We do recognize that the end of life is a very special time,” Rawlins said. “[It] allows people to attend weddings, see a grandchild born, seek forgivenesses.”

But he argued that if Britain spends a lot of money at the end of life, “we’re going to have to deprive other people of cost-effective care.” Rawlins said that might mean spending less money at the beginning of life—and might result in a higher infant mortality rate.

A Cancer Patient Fights Back

“Imagine how I feel when I hear people saying that if they give me the drugs I need to stay alive, babies are dying,” said David Cook, one of a growing number of British cancer patients speaking out against NICE and its rationing formula.

While sipping strong English tea in his village farmhouse kitchen, Cook argued that NICE’s logic breaks down when you go from the abstract formula to specific patients—like him.

A senior government manager in his fifties, Cook was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2004. Two years later his prognosis was bad.

Cook’s doctor said he would die within months unless he got a drug to slow the growth of his tumors. But the cost of the drug was high—too high for NICE in light of the advanced stage of Cook’s cancer—and the NHS refused to pay for it.

Cook fought back. He contended that NICE’s rationing formula calculates cost-effectiveness based on the average patient, but individual patients might do better on a given treatment, which would make the drug more cost effective than NICE suggests. Cook’s doctor believed that was true for him, so Cook pleaded his case before a panel of experts.

“I had to persuade a total of six people that were in the room” he said. “I had to talk for my life.” Cook won his appeal—he got the drug—but he resented that he had to fight for it, that he was treated as an exception.

Cook has other complaints about NICE.

He says the agency treats patients inequitably; it is more likely to reject drugs for rarer cancers like his because the treatments are more expensive than those, say, for breast cancer or lung cancer. “We’re being penalized for having…the ‘wrong’ type of cancer,” he said.

Cook contends that NICE overreaches by measuring the quality of a patient’s life. He said it should not be up to bureaucrats to decide that the life of a bedridden patient, for instance, is worth a quarter or a half that of someone in perfect health.

Cook further argues that NICE neglects an important fact—that by helping a patient live longer, a drug may improve not only that patient’s life but also the lives of loved ones. For his part, Cook remains active and working and has helped care for his wife, who has been diagnosed with breast cancer.

Public Backlash

Stories like David Cook’s—about the government restricting access to life-saving drugs—have become common in the British media. Part of the reason is that many new cancer drugs have become available in the last few years, and some of these drugs are extremely expensive.

NICE’s rejection of such drugs has fueled a growing backlash against the agency. Patient groups and drug companies have called it heartless and indiscriminate.

NICE’s future now hangs in the balance.

In May 2010, Britain’s ruling Labour Party, which founded the agency, lost a general election. The new Conservative-led government has said it will establish a cancer fund, totaling more than $300 million a year, to pay for some cancer drugs turned down by NICE.

This comes at a time of economic crisis in Britain. The government is making large cuts in just about every other public service.

Health economist Alan Maynard of the University of York said it may seem compassionate to set up a cancer fund, but it undermines NICE at a time when the country needs to be reminded of the value of rationing.

These days in Britain, few speak favorably about an agency that was set up to ensure that the government could provide the best care to the most people.

“NICE is not very popular,” said writer Lionel Shriver. “I may be the only fan of NICE in the country. After all, it’s the organization that says ‘no.’”

Shriver is an American who lives in London. Her latest novel, So Much for That, is about the U.S. health care system and how, in her view, it failed a woman who was dying of cancer. Shriver said her novel would have turned out “drastically differently” if she’d been writing about the British health care system.

The novel follows a character who has mesothelioma, a rare but deadly disease that is usually caused by exposure to asbestos. The character is partially based on a close friend of Shriver’s who lived 15 months after being diagnosed with mesothelioma. Shriver says her friend’s treatment cost $2 million.

“If she had been in the UK, that character would have been given palliative care alone,” said Shriver. “They would have tried to keep her comfortable and out of pain, but they would have skipped the major surgery. They would have skipped all that excruciating chemotherapy.”

“I think that my character and indeed my friend would have been better off in the United Kingdom,” Shriver said.

A Model for Other Countries?

Britain’s medical rationing has been noticed around the world. A steady stream of health officials from countries like Brazil, China, and Poland have visited NICE to see if setting up a rationing agency along similar lines makes sense for them.

Some American health care experts wanted to establish an agency like NICE as part of reforming the U.S. health care system. But after Sarah Palin cited Britain as the inspiration for what she claimed was an Obama Administration plan for “death panels,” that idea was dropped.

In fact, in this year’s health care reform law, Congress specifically prohibited British-style rationing. Medicare, for example, cannot apply quality-of-life tests in determining the cost-effectiveness of treatments.

Lionel Shiver is not pleased with that outcome. She said Americans still don’t seem ready to focus on some key end-of-life questions. “At least in the UK we’re having the conversation. How much is a life worth? And what kind of quality of life is that?”

But as other countries look to Britain as a model, it’s far from clear that the model itself will survive.

And that begs the question: Can explicit health care rationing work anywhere if it’s in trouble in the very country that may be best equipped to take it on?

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?