The history of America’s multilingual military

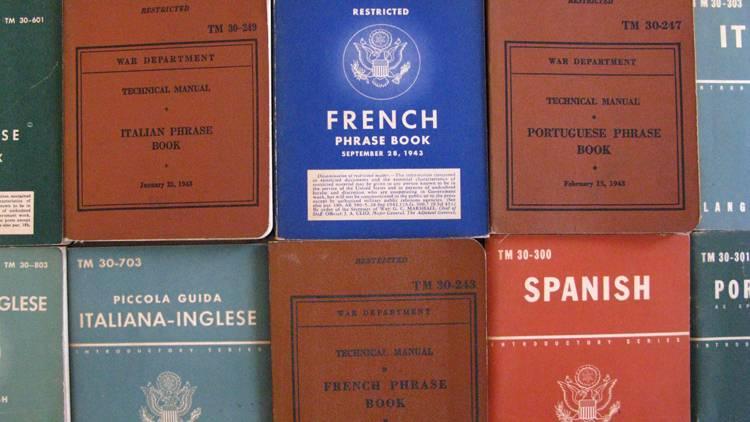

WWII phrase books (Photo: Alex Gallafent)

by Alex Gallafent

A shortage of interpreters and translators has been a recurring theme of the US military’s recent adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan. To make matters more difficult, over the last few years, more than 50 Arabic translators lost their jobs in the military as a result of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

But none of this is to say that America’s armed forces aren’t interested in language training: they are. It just took a long time to get it going.

West Point

The military’s interest in languages goes back a couple of centuries.

When the US Military Academy at West Point was founded in 1802, all the textbooks pretty much that were used for science and military were in French. That’s what was available to the academy. But books are pretty useless if you can’t read them: something had to be done.

“By 1803 Congress authorized money to hire a native speaker to teach French to the new cadets,” said Stephen Payne, command historian at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, Calif.

And so the military’s journey along the linguistic yellow brick road began. First one language was needed, then another. In the late 1840s there was the Mexican-American War.

Payne said that conflict brought Spanish into the military curriculum, in 1854.

Not long after, American interests expanded into the Pacific. The military realized it’d be useful to have officers who spoke the languages of the major regional powers: China and, especially, Japan.

So during the 1920s and early 30s it sent a handful of officers to the embassy in Tokyo for a three-year course in Japanese. But Payne said by 1941, with war against Japan looming, it was clear the United States hadn’t trained nearly enough people.

“It probably had around 60 or 70 officers,” said Payne, “Most of them were either retired or near retirement or were only suited for desk jobs: they weren’t going to be in the field if a war broke out.”

The US military did have some experience with language training. During WWI it ran an enormous program to make sure that thousands upon thousands of enlisted immigrants could communicate with each other. Historian Nancy Gentile Ford wrote a book about soldiers of that time, called “Americans All!”

“While they’re getting the regular training like gas masks and trench digging, they’re also being taught English,” said Ford.

But when it came to the military teaching other languages? Not so much.

WWII phrase books

In WWII enlisted troops were usually deployed to Europe just carrying phrasebooks issued by the War Department. They were encouraged to speak the local language, even for really technical things.

Example: on-deh seh lan-sah-rahn uhs reh-dehs ahn-tee-soob-mah-ree-nahs?

That should produce the Portuguese for: “Where have the anti-submarine nets been placed?”

The WWII phrase books are hugely ambitious in their scope, listing hundreds of specific phrases, from information about time and place to reconnaissance, terrain and weapons.

But not everyone got a phrase book, even. Ronald Freeman was a combat engineer deployed to Germany in 1946, just after the war had ended. He bought himself a dictionary and made do.

“You pick up the language very quickly,” said Freeman. “You learn the expressions that you use, like ‘Wo gehts du?’, ‘where are you going?’ in German. I still remember a few of them.”

The Cold War

It was only after WWII that the Pentagon really ramped up its language programs, resulting in what became the Defense Language Institute. According to Command Historian Stephen Payne, as time went on the military’s language needs started to pile up again.

“Chinese came back,” Payne said. “And then when the Korean War occurs we started teaching Korean. In the meantime we were teaching the language of eastern Europe.”

Most important of all, the school began teaching Russian. In a promotional movie for the school from the 1960s, an American officer is quizzed on the technicalities of a Russian tank.

“The desired response should be one that might win total approval from the most exacting of Russian instructors,” the officer said. “Describe briefly the medium tank T-34.”

That kind of technical knowledge of a language takes time. While the military needed to know Russian back then, now it needs different languages.

In depth language learning has always been prioritized based on strategic need. When you’re talking about a language taking two years or more to learn, that need is often a best guess.

“We actually taught Persian Farsi in the 1980s and we stopped teaching that around 1990,” said Payne. “And we had to start that program up from scratch after Sept. 11.”

The world changes in the blink of an eye. And so while the US military will continue to produce language specialists, it’s now intent on being linguistically nimble too.

It’s using technology to do it.