When residents of the small Nahua community of Santa María Zotoltepec first heard about the proposed gold and silver mine about a decade ago, they were excited.

They thought about jobs and development in their area, nestled in the Ixtacamaxtitlán municipality’s highlands of Puebla state, Mexico.

Nearby were 7 million ounces of gold and 1.4 billion ounces of silver, according to mining company Minera Gorrión, a subsidiary of the Canadian corporation Almaden Minerals. The company promised that mineral extraction would bring benefits to the community — including 420 jobs and millions in local tax revenue.

Related: Desalination brings fresh water — and concern — to an Indigenous village in northern Mexico

“At first, you can’t imagine how excited we were. How this company was coming to bring us work. It’s going to change our way of life.”

“At first, you can’t imagine how excited we were. How this company was coming to bring us work. It’s going to change our way of life,” said Raymundo Romano, from the Union of Atcolhua Ejidos and Communities.

But reality slowly set in. “We started to see that this project was not good,” Romano said. “The company was going to threaten our lives, threaten our water.”

After a seven-year battle led by Indigenous communities, Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled in mid-February to cancel Minera Gorrión’s mining concessions in Ixtacamaxtitlán because the company had failed to consult with local people on the mining project.

It was a huge victory for the community.

A month later, in mid-March, another federal court canceled three more mining concessions in a different Puebla region, when it ruled that the Indigenous Masewal people had also not been consulted about the mining project with another company in their community.

The two cases may set a precedent against potential mining exploitation in the future.

Related: The debate over deep-sea mining comes to a head

Protecting water and land rights

Mining requires tons of water — a resource lacking in a region recently plagued by drought. At least 20 municipalities in the region currently lack sufficient water supply.

Minera Gorrión had promised to build a new water reservoir for surrounding residents. But the mine would use an estimated 1.3 million gallons of water a day to process the gold and silver.

Pristine hillsides were at risk. Community members feared their springs would be contaminated. They feared for the Apulco River, which runs from their mountain home, down to the Veracruz coast on the Caribbean.

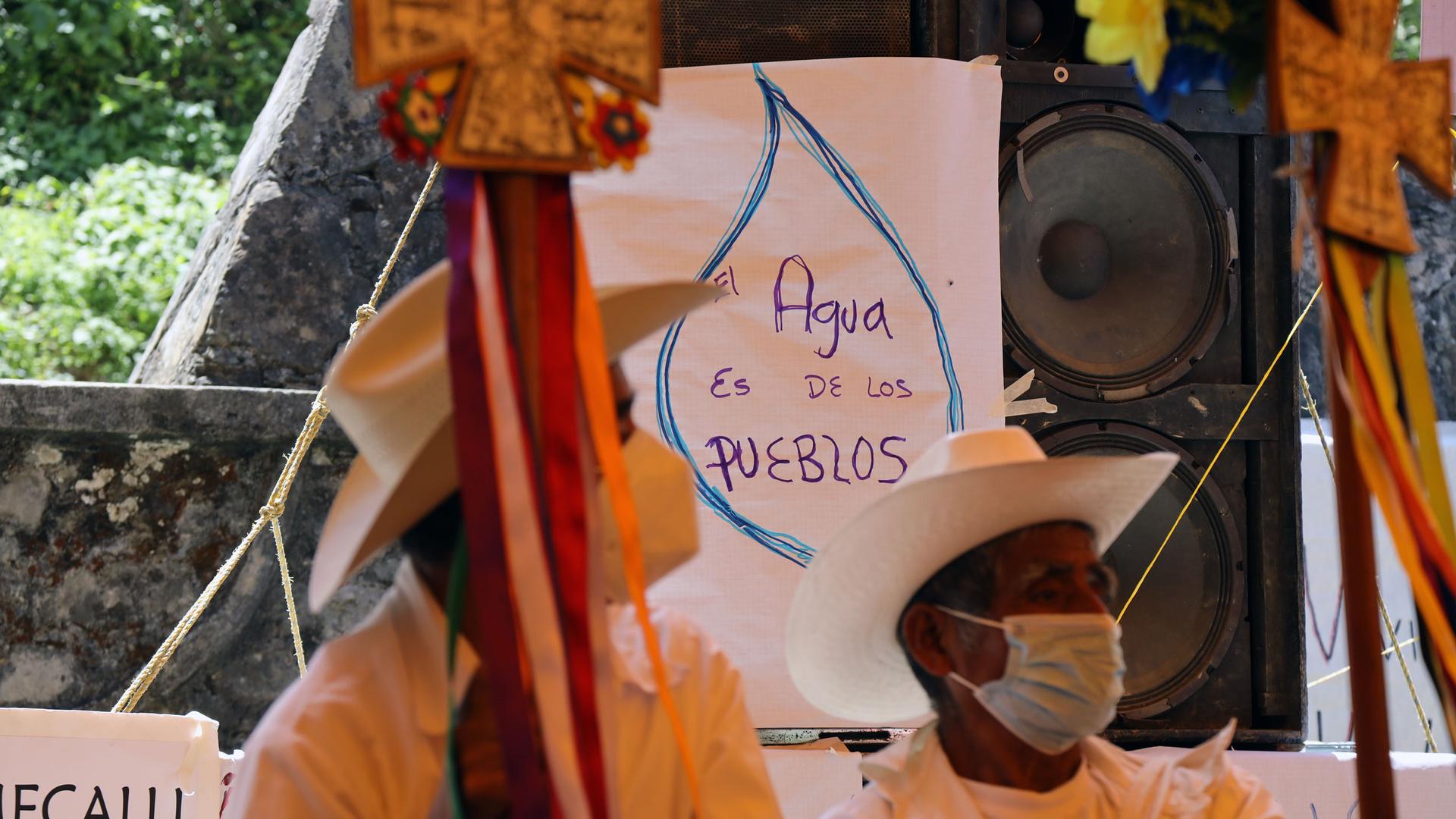

So, in 2015, the community of Tecoltémic, which neighbors Santa María Zotoltepec, took the mine to court, winning an injunction. The mine appealed. The case rose in the courts. Communities marched and protested before the Supreme Court.

“We could not be happier,” said Augusto Rodriguez, who lived near the mining project. “We were very concerned before, and now we are really relieved.”

Both rulings are landmark cases for Indigenous struggles against mining in Mexico.

“I dare to say that we are at the doorstep of a new paradigm in the relations of the judicial power with the rights of Indigenous people.”

“I dare to say that we are at the doorstep of a new paradigm in the relations of the judicial power with the rights of Indigenous people,” said Yoatzin Popoca, a lawyer with the Mexican Center for Environmental Law, a nongovernmental organization that worked on the Masewal case.

Related: Mexican communities manage their local forests, generating benefits for humans, trees and wildlife

‘We have to unite’

Hundreds of Indigenous people in the highland town of Ahuacatlán celebrated these victories in late March. And about100 Indigenous activists on a monthlong caravan in defense of Indigenous land and water rights across southern Mexico made this one of their first stops.

At least 30 different groups have signed on to the caravan, including the National Indigenous Congress and United Peoples of the Volcano and Cholulteca Region.

“This is the only way we can stop these megaprojects dressed up as development. … We have to build these networks. … We have to unite.”

“This is the only way we can stop these megaprojects dressed up as development,” María de Jesús Patricio told a crowd at the launch in March. She’s the former presidential candidate for the Zapatista, a radical Indigenous social movement that rose up against the Mexican state in 1994.

“We have to build these networks,” she said. “We have to unite.”

For the next month, the caravan will be visiting communities in nine states that are also facing threats from mines, dams and other extractive industries. Ahuacatlán is a municipality that, in recent years, has been in the middle of plans for both mines and three hydroelectric dam projects.

“It’s good what the caravan is doing. … Because we are not fighting just for one person, but for all of us. We are fighting for our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren. Those are the ones who will suffer even more.”

“It’s good what the caravan is doing,” said small farmer Santiago Pedro, who met with the caravan in Ahuacatlán. “Because we are not fighting just for one person, but for all of us. We are fighting for our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren. Those are the ones who will suffer even more.”

In Ahuacatlán, they held religious ceremonies. They ate, sang and danced. They committed to stand up to attacks on their land. They also shared stories of hope, like those of the recent court victories.

An uphill battle

Those in attendance said they still face an uphill battle. Romano and others fear the companies will try to overturn the rulings. They say Mexico’s Mining Law itself needs to be changed to meet the environmental needs of Indigenous groups.

Over 8% of Mexican territory is concessioned to mining.

“We are one of the top 10 producers of the most precious minerals in the world,” said Valentina Campos Cabral, director of Iberoamerican University’s Environmental Investigations Institute. Total mineral and mining production in 2020 was worth almost $14 billion.

Indigenous communities say they are going to be more united than ever.

“Everyone should know that the municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlán is against the projects that threaten our lives,” Romano said. “And that’s the way it’s going to be. Any other municipalities that need our support, you’ve got it.”