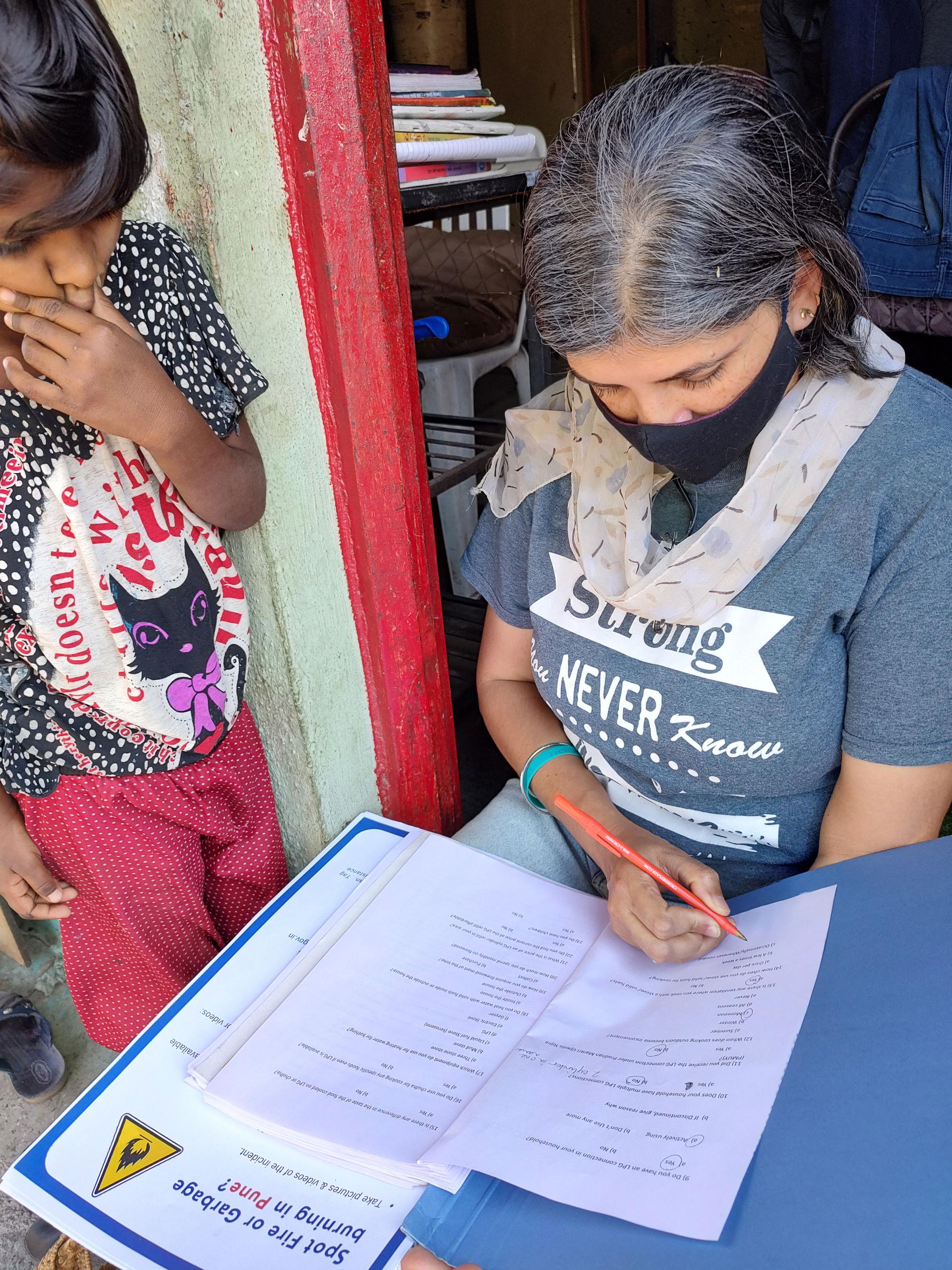

Anuja Bali asks a family in Pashan, Pune about their consumption of liquid petroleum gas.

Educator Anuja Bali is on a mission to teach women in India about the dangers of indoor air pollution — what she calls a “silent killer.”

In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, Bali co-founded a group called Warrior Moms to mobilize women to draw attention to the issue. In two years, the group has drawn more than a thousand women from across the country, tackling the issue through grassroots education and policy interventions.

The dangers of breathing in fumes from cars, construction and burning crops are well-known, Bali said, but harmful exposure to everyday household smoke from cooking and heating is largely misunderstood.

Related: Did the world ‘build back better’ since the start of the pandemic? Not so much.

“Air pollution is a silent killer. … And people are just not giving importance to this huge source of pollution — which is harming our children.”

“Air pollution is a silent killer,” Bali said during a recent education drive in Pune, a city of 4 million south of Mumbai, in western India. “And people are just not giving importance to this huge source of pollution — which is harming our children.”

Members across 12 cities work in small groups in person and online to share multilingual resources and teaching materials. Volunteers like Bali also conduct informal education drives to teach communities about the dangers of indoor pollution.

Government data indicates that more than 70% of Indian households have a gas stove or use gas supplied in 14-liter cylinders of Liquid Petroleum Gas, commonly known as LPG. At Bali’s home, for example, she uses LPG gas for cooking (and electricity to heat up water).

But just a half mile from her high-rise apartment, residents live in small, one-room dwellings. Here, smoke rises daily with the use of a chulha — or clay stove — to cook and heat bathwater, Bali said. The chulha burns timber, coal, cow dung, or even dry leaves, paper or plastic — all forms of fuel that emit excessive smoke.

Related: Seemingly small shifts in global temperatures have huge consequences for the planet

Bali has conducted over 100 surveys in the last year within Pune’s lower-income communities to assess why women continue to use chulha instead of the cleaner, safer LPG gas, which emits less smoke.

Most survey respondents say LPG usage is just too cost-prohibitive. A standard LPG cylinder costs $12 a month. In her survey groups, the average wage was under $2 a day; respondents said shelling out this lump sum for a cylinder is untenable.

Resident Pooja Yadav, a young mother of three, said she doesn’t like using the chulha, but her last gas cylinder ran out after only 14 days and she could not afford a refill.

Onita Orsul also has a gas cylinder at home, but since her son lost his job during the pandemic, they can’t afford gas refills, she said. Instead, she uses her chulha to heat water and cook.

Related: The invasion in Ukraine could mean less reliance on energy from Russia, analyst says

Bali said nearly everyone complains of eye irritation, allergies, coughing — even cataracts. She points to research linking low birth weight and stunted growth to indoor air pollution.

Indoor air pollution also leads to respiratory, pulmonary and cardiac diseases, according to Avinash Kishore, a research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Delhi. Women and children are most impacted by indoor air pollution, according to his research.

Poor women in remote areas who cannot afford or cannot access the LPG registration and refill infrastructure are most affected by indoor air pollution, along with young children who stay close to their moms.

“Even if you think about intersectionality, even among women, it’s the poor women in the remote, remote areas who cannot afford or cannot access the LPG registration and refill infrastructure,” he said. “And then the second most affected are children, especially young children who stay close to their moms, indoors.”

The air quality index, which measures the concentration of particulate matter in the air, should fall below 50 to be considered safe, Kishore said. Above 300 is considered hazardous.

Closed, unventilated kitchens often reach an AQI of 20,000, Kishore said.

Yet, living on a shoestring budget means having to set priorities, Kishore said.

Related: This citizen scientist is on a mission to help gauge air quality in Central Asia

“Firewood is free if you can gather it yourself and if you can’t, you can still buy just a few days’ worth at a go,” he said.

The government used to subsidize LPG connections but in May 2020, those subsidies ended. Kishore recommends restarting them for households that cannot afford LPGs in their homes, while ensuring the system is not abused – a common criticism of the previous scheme.

The Warrior Moms tackle other areas like accessibility and education.

Back at the settlement near her apartment building, Bali cuts an unusual but familiar figure. She’s often present on a weekly basis with questionnaires and posters.

She takes an informal approach to teach families about the harmful effects of air pollution, from tree-cutting to garbage-burning.

In one woman’s home, when Bali spotted plastic milk packets in the firewood pile for her chula, she likened it to smoking cigarettes.

“By burning plastic packets, you may as well just light up a cigarette because the smoke from this will do the same thing to your lungs,” she told the woman.

She explained that it brings cancer into the home. Message received. The woman fished out the plastic packets from the pile.

The Warrior Moms don’t make policies, but they work to link their findings with policymakers.

Warrior Moms in many cities are all pushing for what they call the “chulha-free” campaign — to secure cleaner cooking fuels for area women and their families.

They collect and collate data on chulha usage; adverse health effects such as allergies, coughs, eye infections; and affordability factors for cleaner fuel options.

All of the women Bali surveyed said they’d prefer LPG cylinders to chulah, if given a choice.

This localized data is then shared with each constituency’s elected officials.

Ahead of Pune city’s municipal elections, the group has asked local officials to make gas connections available to everyone.

“This is the perfect time to ask them: Get all these people LPG connections and give them solar water heaters for [each settlement’s] public bathrooms, and then they’ll vote for you,” she said.

They hope to see subsidies for women to help them make the switch to LPG as their main fuel source.

The Pune-area Warrior Moms anticipate the release of a new city budget in the coming weeks to gauge the impact of their advocacy for cleaner indoor air quality for everyone.