This ‘living lab’ in Sweden experiments with the future of sustainable cities

When social scientist Helena Strömback thinks about sustainable living, energy-resilient meal kits come to mind.

Working with the assumption that power will be less dependable in a low-carbon world, she encourages the use of groceries, recipes and techniques best-suited for cooking when the power is low or unavailable.

Strömbackis a researcher at the Living Lab, in Sweden, at the forefront of a global movement to find actionable ways to mitigate the impact of climate change in cities.

“If you have an outage at meal time, it will still be a good meal,” she said, noting that zero-energy cooking like pickling or fermenting can also “create that feeling of a cooked meal.”

The Living Lab was launched in 2016 by HSB, Sweden’s largest housing cooperative, which pioneered the modern Swedish kitchen, bathroom and indoor waste disposal system.

It operates out of a four-story building on the campus of the Chalmers University of Technology in the southern Swedish city of Gothenburg.

There, a group of 40 resident students and researchers spends their days developing, testing and showcasing the most innovative low-carbon, energy-conserving building technologies of the future.

Related: Amsterdam bans fossil fuel ads from its metro

The world is now on course to warm by a catastrophic 2.4 degrees by the end of this century.

Urban areas account for an estimated 75% of Earth-warming carbon emissions, with transportation and buildings contributing the most. And buildings account for over a third of global energy consumption and carbon emissions.

“We have 2,000 sensors incorporated in the building’s structure that measure everything the residents do — water usage, electricity usage — to determine if any new products or services that we install in the building have an effect, sustainability-wise.”

“We have 2,000 sensors incorporated in the building’s structure that measure everything the residents do — water usage, electricity usage — to determine if any new products or services that we install in the building have an effect, sustainability-wise,” Living Lab’s manager Madelaine Doufrix said.

Sweden generates 45% of its power from hydroelectricity, 45% from nuclear and 10% from wind and solar. Living Lab researchers want to optimize that renewable slice, with heating at the top of their agenda. The building itself is heated geothermally, with municipal district heating as a backup.

Related: Building high-rises, hotels and stadiums out of wood — for climate’s sake

A host of smart devices within the Living Lab boost energy efficiency.

With the tap of a smartphone, an electric car charger outside kicks in when solar batteries on the top floor are full. Those batteries, fed by rooftop solar panels, are scheduled to charge and discharge over the same cycle.

On the ground floor, the washing machine can get programmed to start in the evening, when energy is cheapest (based on spot-market prices monitored by the machine’s software), or at a low carbon-emission setting.

To boost energy efficiency at the Living Lab, sink and shower water, and the heat, are recycled (toilet water is not).

Swedish engineer Per Ericson designed the gray-water recycling system that captures, filters and sends water back upstairs, along with its heat, reducing water-heating costs by a half and cutting 60% on water consumption.

“The biggest reaction we get from the tenants here is that they’re kind of uncomfortable showering in recycled water.”

“The biggest reaction we get from the tenants here is that they’re kind of uncomfortable showering in recycled water,” Ericson said.

Many wonder at first if the recycled water is clean.

In fact, recycled water at the Living Lab is cleaner than tap water. The system detects pollutants such as urine and sends them down the drain. Ultra-efficient filters remove everything down to the tiniest bacteria and viruses, including the bacterium that causes Legionnaires’ disease, a nasty respiratory infection.

Once residents understand that recycled water is clean and that it’s so economical, they’re convinced, Ericson said.

But Living Lab residents don’t need to be persuaded about the benefits of recycling garbage. In the trash room, residents use multicolored bins for paper, plastic, glass, organic waste and even one for electronic waste. A sensor inside each bin sends a message to municipal waste managers when the bin is full to avoid wasting energy picking up half-full bins.

In the future, the Living Lab may install molecular-solar windows that capture sunlight — they would be coated with a molecule that absorbs solar energy, transferring its heat inside when the sun sets.

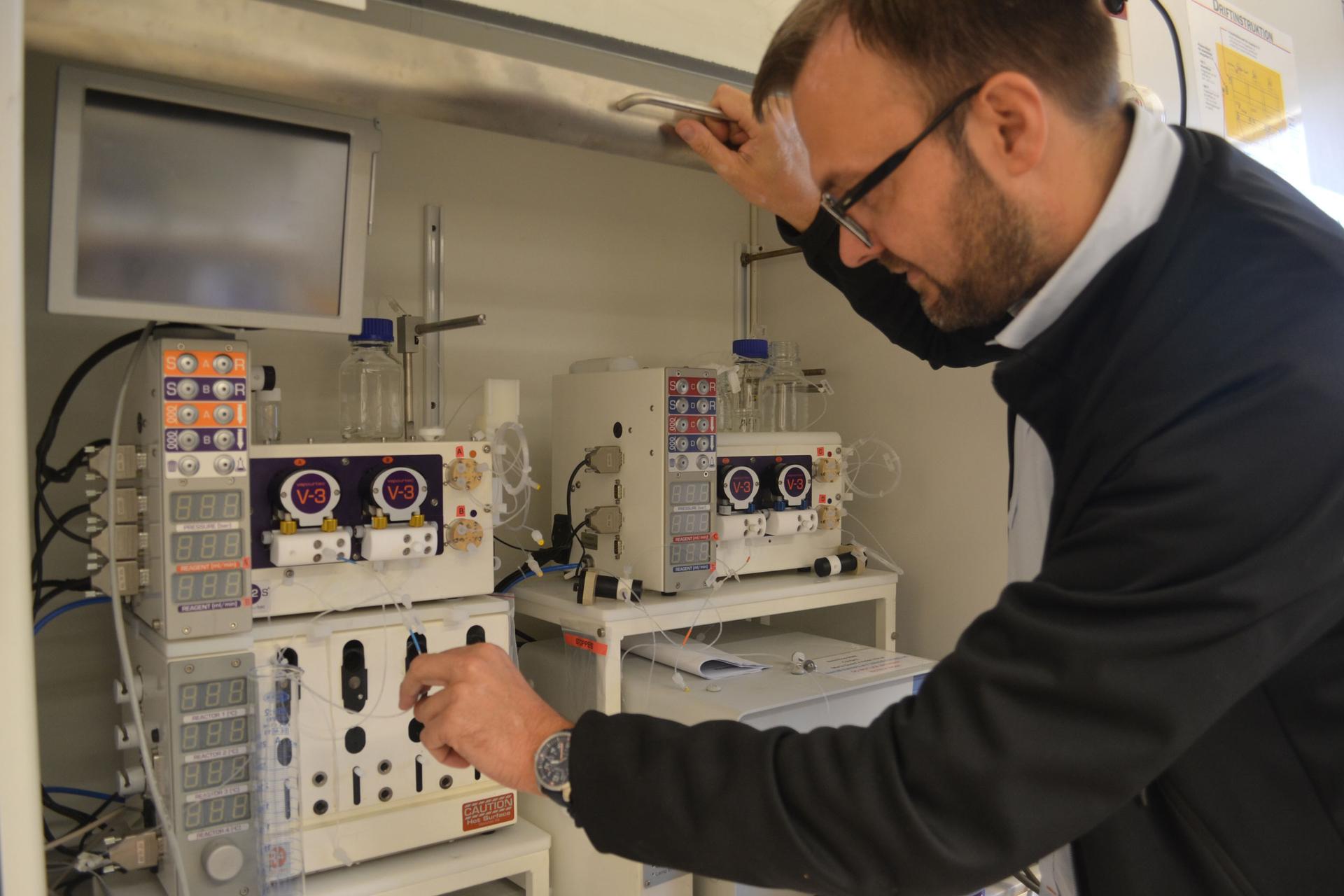

Kasper Moth-Poulsen is developing this heat-absorbing molecule at a couple of organic chemistry labs across Chalmers campus from the Living Lab.

The goal is to produce a molecule that absorbs the most sunlight, holds energy the longest, and then, releases it in a controlled fashion.

His hope — once the molecule is perfected — is to partner with a chemical company that can mass-produce it. To date, however, Moth-Poulsen’s light-absorbing molecule has only been produced in small quantities.

Back at the Living Lab, resident researchers also monitor an online beehive out of concern for the future of bees and other pollinators crucial to humanity’s food supply. Installed sensors inside the hive allow the researchers to monitor the honey bees.

Student resident Stig Robertson doesn’t mind that, like the bees, he, too, is monitored as part of the experiment in sustainable living.

“You don’t really see it that much,” Robertson said. “I mean, you see the sensors. Part of the experiment is that we don’t really think about being in an experiment all the time, right? In that sense, it’s working.”