As the world careens toward the end of a wild year, plans for New Year’s Eve may simply entail taking a deep breath in — and exhale.

With a life-altering pandemic, global cries for racial justice and a contentious US presidential election, this year ushered in unprecedented uncertainty, economic turmoil, anxiety and fear.

Related:Pandemic stress overshadows US election for this young Latina voter

Amid lockdowns, shutdowns, quarantines and travel restrictions, many found ourselves wandering the hallways of our lives, wondering what to do with this new living-room paradigm. The pandemic also magnified protracted, global inequalities and exposed those faultlines as essential workers headed out to the pandemic’s frontlines.

Related: Isolation may be a greater risk than COVID-19 for Canadian nursing homes

Researchers have predicted a global mental health crisis that will last for years after the pandemic ends, with millions forced into isolation and millions more out of work while simultaneously dealing with death and disease. In May, the United Nations warned that the situation is compounded by decades of ignoring and underinvesting in mental health needs, especially in conflict-hit communities.

For some, it’s already led to “pandemic fatigue” as we try to maintain public health measures like physical distancing and mask-wearing. And mental health concerns have been even greater for students of color throughout the pandemic.

Related:Hoarding, stockpiling, panic buying: What’s normal behavior?

Back in February, when the pandemic first hit Wuhan, China, a hotline for health care workers offered critical support for those overwhelmed by the coronavirus crisis. In the US, activists organized a therapists’ network to provide urgent mental and physical health care to immigrants. And in Sweden, Stockholm’s mental health ambulances may help the US rethink policing.

With time redefined and priorities reshuffled, the world responded with unusual ways to break through the madness, heal shattered realities and connect across these strange, new boundaries.

Related:Pandemic’s disruption to the grieving process could have lasting effects

From the sourdough baking revolution to knitting, running, or shouting into the void, here are some of the most innovative ways people around the world coped with 2020.

1. Scream into the void

Letting out a good scream can be really cathartic and there isn’t a wrong way to do it. People in Iceland have done this for decades but this year the primal scream found renewed interest as an effective way to relieve stress, and this is backed up by plenty of research.

Zoe Aston, a psychotherapist in the United Kingdom, told The World it’s a technique called primal therapy. “Primal therapy was a type of therapy that was used a lot in the 1970s and rather than sitting and talking, they took people out into wide open spaces and they encouraged people to kind of let go of some of those really pent up emotions,” Aston said.

2. Bake tons of bread

For people with time on their hands during lockdowns and quarantine periods, many struck up a new relationship with bread — kneading, baking and eating it.

While millions were confined to their homes worldwide, baking projects have been on the rise and sourdough bread, in particular, was having a moment during the pandemic. Google trends reported a 40% increase in the search term “sourdough” since early March, even though making this type of bread requires a pretty complicated handmade yeast known as a “starter.”

Luckily, Karl de Smedt, the curator of the world’s only sourdough library, had some tips for sourdough enthusiasts. “As long as you feed it, it has eternal life,” he said. “As long as someone feeds it with flour and water, you can keep it alive for thousands of years.”

3. Solve a mysterious puzzle

Some with time on their hands took up reading or knitting to pass the time or cope with stress. But British comedian John Finnemore made it his quarantine project to crack “Cain’s Jawbone” — and he succeeded, making him just the third person to solve it in its nearly 90-year history.

“Originally I had a look at it and decided that it was too difficult for me and there was no point. So I just put it back on the shelf,” Finnemore said. “Then the pandemic came knocking…and suddenly said, ‘You know all that time you wanted, to do that thing? Well, here you go, knock yourself out, you’ve got as much time as you want.’”

4. Experience art

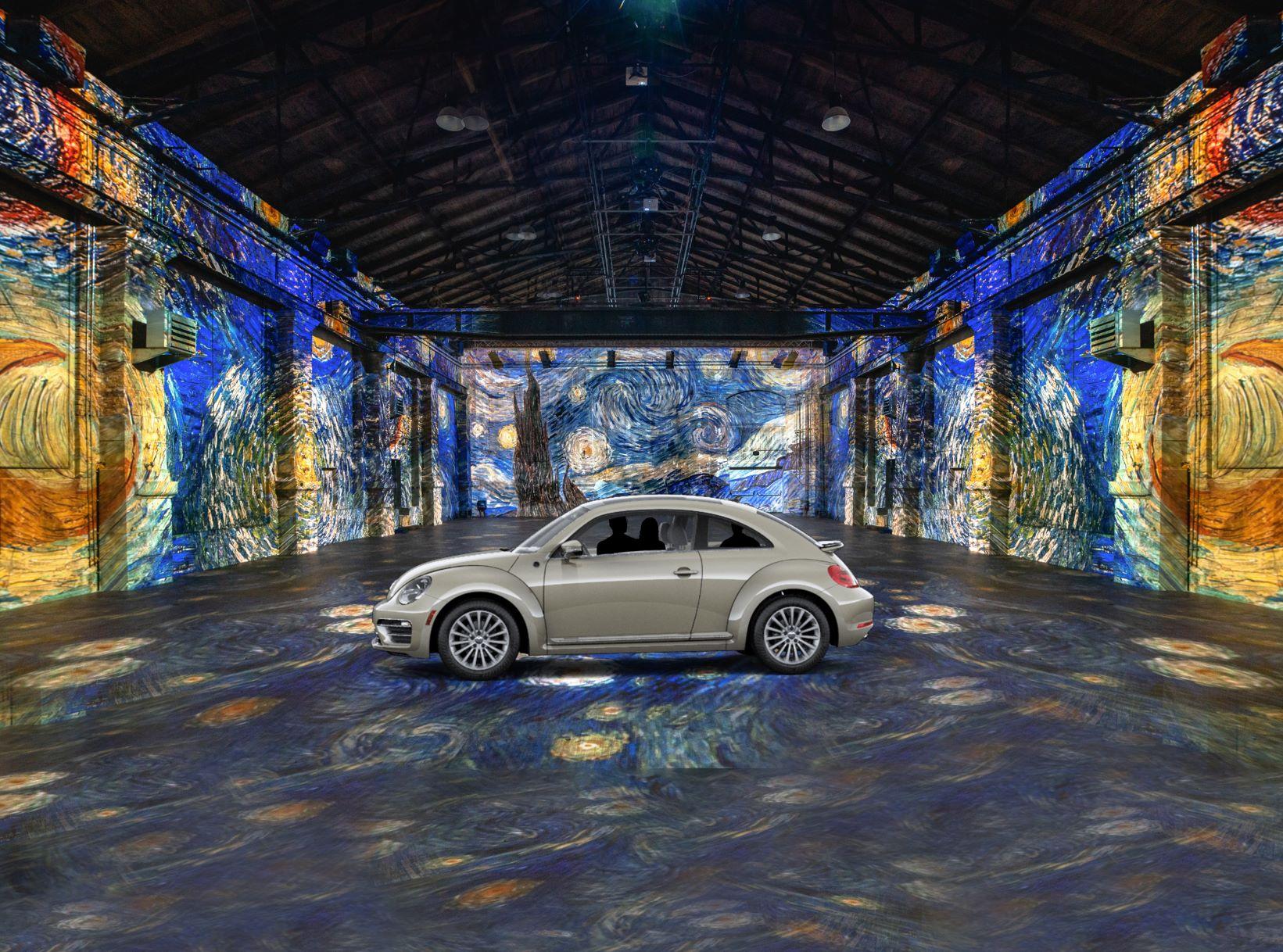

As doors to our favorite cultural spaces closed, cultural institutions scrambled to stay connected with patrons and keep their exhibits alive. “Gogh by Car,” presented by Toronto’s Lighthouse Immersive Arts invited viewers to experience the art of Vincent Van Gogh safely from their cars as a drive-in art exhibit.

“The appeal I think right now is very simple: Everybody is really tired to be at home. To do something fun, to do something outside of your house — is desperately needed,” said Svetlana Dvoretsky back in May.

Artists found other ways to experience and make art together through collaborations and online festivals.

5. Sing — or write — through the pain

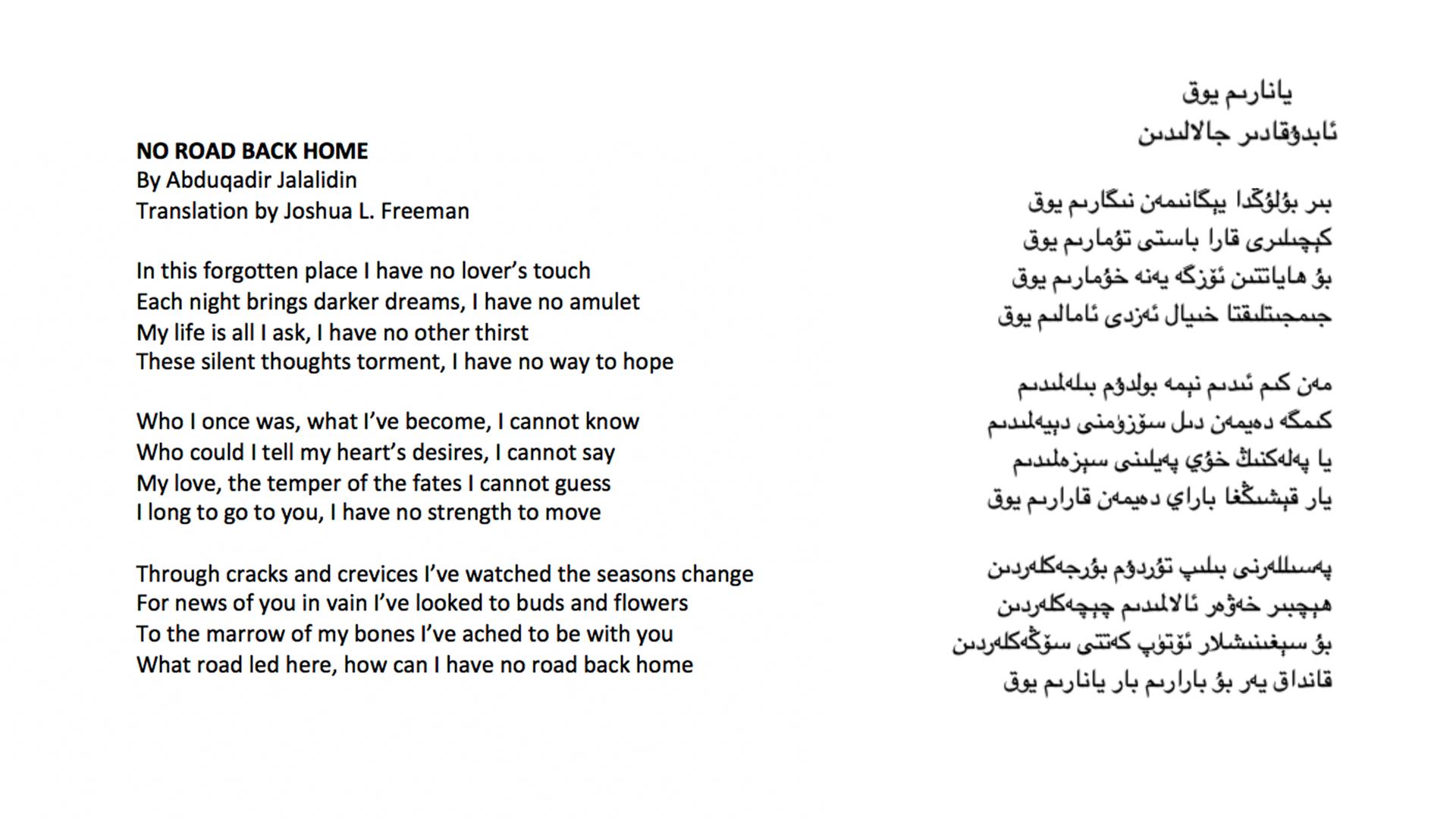

Poets, novelists and musicians have long used their art forms to express the fear and despair that defines life during a pandemic. This year, Abduqadir Jalalidin, a detained Uighur poet, bore witness to the suffering of Uighurs held in a Chinese internment camp, and his poem traveled through word of mouth to New Jersey.

“I was deeply moved that other inmates had managed to get this poem beyond the camp. I felt that this was a witness that the world needed to hear, that this was a testimony the world needed to hear,” said Joshua Freeman, a historian and Uighur poetry translator, and friend to Jalalidin.

In Spain, at the height of its coronavirus crisis and under lockdown, three roommates, all musicians, decided to create music that would help their neighbors get through the “confinement blues.” Dubbed the Stay Home Band, they became an overnight sensation with a reggae-style song urging people to stay home. Within hours of posting it, the song had thousands of views — clearly a sign that music connects and heals.

“People kept asking for more,” said Rai Benet, one member of the trio. “And we thought, why not? We have nothing else to do.”

Weeks later, and with at least 24 more songs, they have hundreds of thousands of followers from all over the world.