New app helps Inuit adapt to changing climate: ‘It’s time for the harpoon and computer to work together’

In one SIKU app post, 73-year-old Jimmy Iqaluq explains why this past winter’s sea ice was too thin to hold the weight of a snowmobile due to warm temperatures.

Mick Appaqaq has been going out onto the rugged, isolated land around the Hudson Bay since he was little.

Appaqaq lives in the town of Sanikiluaq, on Flaherty Island, one of the thousands of small islands that make up Canada’s northernmost territory of Nunavut — which stretches deep into the Arctic.

“My father would always take me geese hunting in the spring and berry picking in the summer, ever since I was a young kid. … So, yeah, it’s in my blood.”

“My father would always take me geese hunting in the spring and berry picking in the summer, ever since I was a young kid,” he said. “So, yeah, it’s in my blood.”

For much of the year, Nunavut’s coastline and islands are interlaced with sea ice that must be traversed to get to fishing and hunting grounds. Priority number one is not falling through, Appaqaq says.

To make sure it can hold the weight of a snowmobile, hunters often use a harpoon to punch through ice — a traditional method used by the Inuit for countless generations. But now there’s another step.

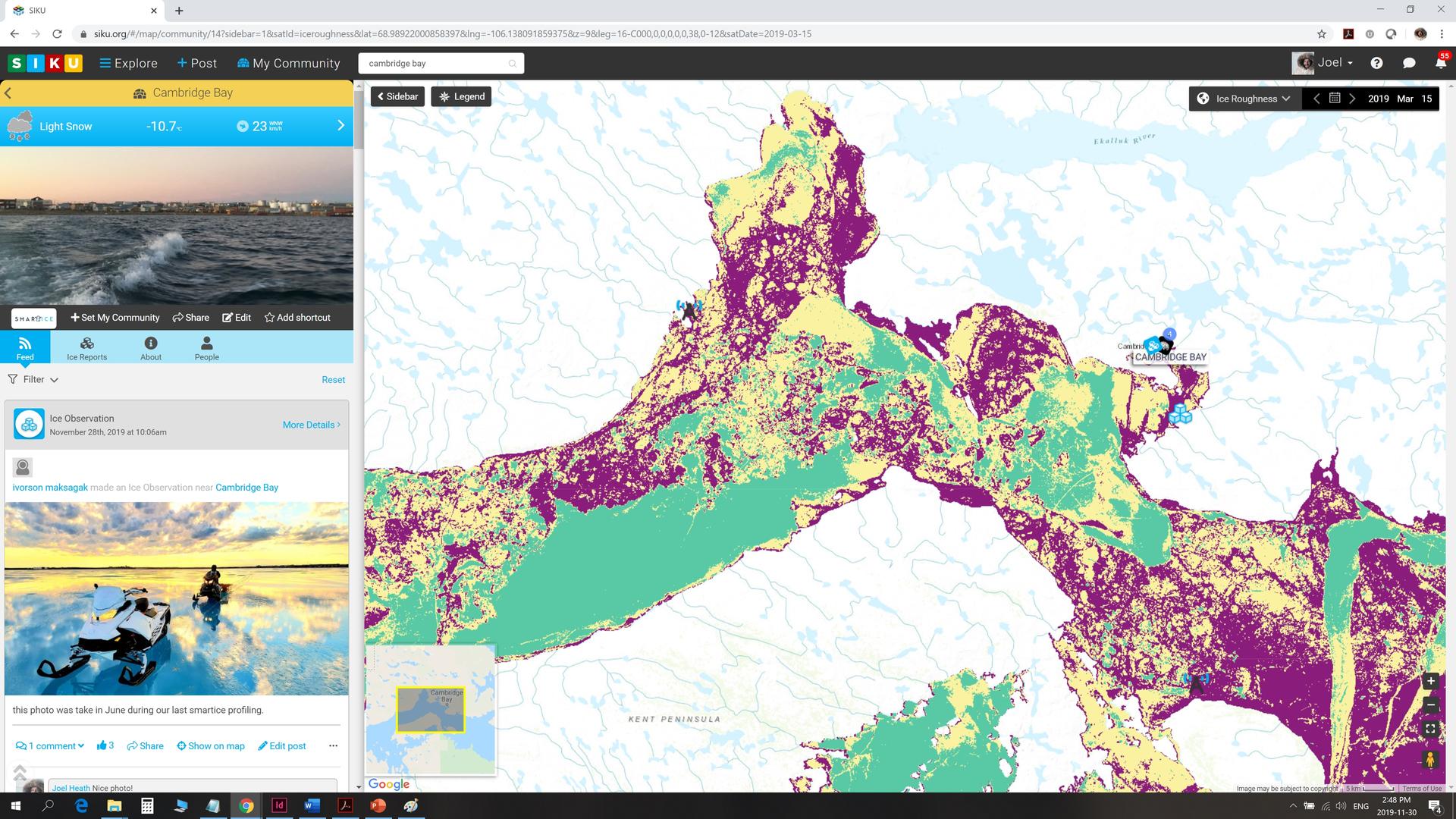

If the ice is indeed too thin, Appaqaq will grab his phone and open an app called SIKU — which means “sea ice” in Inuktitut — and upload a photo of the thin ice to alert other hunters of hazardous ice conditions.

In a changing Arctic, apps like SIKU can provide new tools for both real-time monitoring and long-term data gathering to give communities the ability to notice trends and plan for the future.

In recent years, climate change in the far North has led to dangerous ice conditions as the region is expected to warm more rapidly than almost anywhere else in the world. The impacts of global warming pose grave threats to the safety of these communities — as well as their livelihoods.

SIKU launched last winter after being developed by the Arctic Eider Society, an environmental and social justice organization based in Nunavut. The app has funding from private foundations, the federal government and regional Indigenous governments. It now has more than 6,000 users.

Appaqaq, who works as a technician for the app, said it was partly inspired by a recently deceased elder, who wanted to merge old ways with new tech.

“It’s time for the harpoon and the computer to work together.”

“He said that it’s time for the harpoon and the computer to work together,” said Appaqaq. “You’ll meet two worlds. You meet the traditional way and the modern way in order to tell stories of where you got this animal, where you crossed this piece of land.”

Young people have been using SIKU with their grandparents to record ice conditions and possibly unusual behavior of wildlife, said Appaqaq.

One elder who makes a regular appearance on SIKU is 73-year-old Jimmy Iqaluq, who is an expert at “reading” sea ice.

In a SIKU video post from February, in his native Inuktitut, Iqaluq points to the sea ice around him and explains that this past year, the sea ice was different because abnormally warm weather prevented it from getting thick enough.

Iqaluq’s observation belies a wider phenomenon. This past summer, due to intense summer heat, sea ice in the Arctic melted to its second-lowest extent on record.

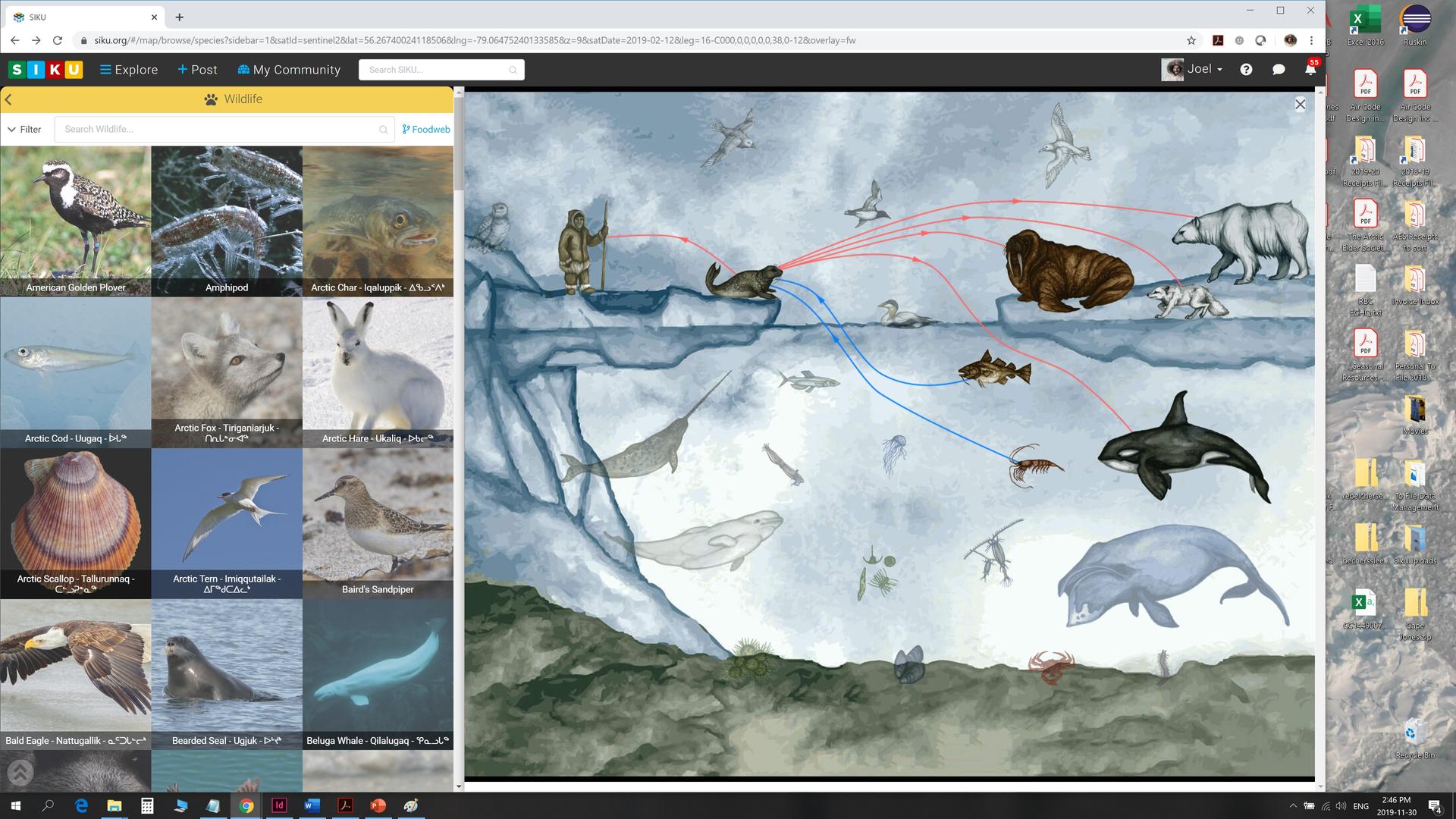

It’s not just affecting the ice. Climate change is also affecting animal species important to the Inuit diet, such as Arctic char and caribou.

In the SIKU app, people can post where they hunted snow geese, picked ripe berries, saw moose tracks, or caught fish. The app can be used by people to do real-time monitoring, but its founders hope it can also provide a long-term benefit.

“At a time of rapid change, conventional methods of data gathering are insufficient to meet the challenge. …Whether the challenge is declining populations of wildlife, rapidly changing habitat or changing sea ice conditions.”

“At a time of rapid change, conventional methods of data gathering are insufficient to meet the challenge,” said Denis Etiendem Ndeloh, director of wildlife management at the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board. “Whether the challenge is declining populations of wildlife, rapidly changing habitat or changing sea ice conditions.”

Etiendem Ndeloh helps operate a community-based monitoring program similar to SIKU. It also has a new app that makes it possible for community members to track wildlife observations.

For example, Etiendem Ndeloh said, caribou populations are in steep decline in Nunavut. Keeping track of caribou movements can help communities make long-term decisions about where to hunt and where to have protected areas.

“The Arctic is really in need of all of these programs, injecting new technology to monitor sea ice, changing weather conditions, wildlife populations and patterns and trends,” he said. “Programs like our community-based monitoring network and SIKU are critically important in understanding and managing change.”

Prior to SIKU, many users of the app would post their wildlife observations on Facebook, where the data no longer belongs to them.

“With SIKU, you can download your own data, you own all your own intellectual property rights. …It’s really designed to respect Indigenous knowledge and allow full ownership, access and control by the users.”

“With SIKU, you can download your own data, you own all your own intellectual property rights,” said Joel Heath, a SIKU co-founder. “It’s really designed to respect Indigenous knowledge and allow full ownership, access and control by the users.”

Heath said conventional methods of data-gathering involves scientists coming from outside the community, making observations and leaving. SIKU could completely change that dynamic.

“[Inuit communities] have a deep understanding about the ecological processes and physical processes here,” said Heath. “[SIKU is] empowering people with tools that help document the data that’s always been behind Inuit knowledge. It’s a transition from oral history to being able to document it systematically.”

Now, they’re working to get the app translated into different dialects of Inuktut to make it more accessible.

“There’s many different dialects, basically almost every community has their own dialect,” said Candice Pedersen, whose job is to help Inuit communities all over Nunavut learn to use the app.

Pedersen says as an Inuk woman, she also wants SIKU to expand beyond hunting and fishing.

“We’re trying to work on stuff so that you can have sewing posts or recipe posts to get more people involved in the app,” she said. Her own profile has two badges on top, one with a spear signaling she is a hunter, and another with a sewing machine signaling she is a seamstress.

“I’m hoping that SIKU will become the new Facebook for a lot of people,” she said.

A network that keeps people in touch — not just with each other — but with the changing North.